For the past two hours we have been driving from the frontier town of Lago Agrio, the birthplace of oil extraction in the Ecuadorian Amazon, heading West towards the Andes, following the extended tentacles of the oil industry that criss-cross what was once a mega-diverse rainforest. As far as the eye can see, oil fields, pipelines, pastures and small towns of settlers or “colonos” now populate the scenery in one of the most active deforestation hotspots of the entire Amazon.

After crossing the Due River, a tributary to the Aguarico, the caravan of the A’i Cofán Guard (or land patrol) enters the Cayambe-Coca National Park, one of Ecuador’s largest protected areas. Here the Amazon collides with the Andes in a spectacularly diverse display of landscapes and wildlife. Amongst the most biodiverse regions in the world, this one-of-a-kind refuge for jaguars, spider monkeys, mountain tapirs and over 600 bird species overlaps with ancestral Indigenous A’i Cofán territories. One of the A’i Cofán communities is Sinangoe, whose culture and way of life has maintained balance with the rainforest for thousands of years, and whose fierce struggle to protect their territory was recognized by this year’s Goldman Environmental Prize.

If it wasn’t for the green patch on the guard’s GPS showing that we are already several miles inside the National Park created by Ecuador’s government back in the 1970’s, nobody would think that this is actually a “protected area.” Shockingly, all around us are acres upon acres of recently deforested plots cleared for cattle ranching, a maze of roads, new settlers’ houses and, a couple of miles further inside the Park, a recently built hydroelectric dam. “Welcome to the jungle” one of the A’i Cofán leaders says, while pointing to the barbed wire and twelve cows grazing behind him. “This is what government-led conservation looks like.”

The Due River Valley, inside the Cayambe-Coca National Park, has been transformed by cattle ranching, road building and hydroelectric development over the past decade.

The A’i Cofán have good reason to be upset. Not only is there rampant deforestation inside the National Park without any apparent control by Ecuador’s Ministry of the Environment, Water and Ecological Transition (MAATE), but a week before, during a routine boundary scouting, the A’i Cofán Guard found that cattle ranchers had also trespassed into their ancestral territory, destroying over 25 acres of intact rainforest. This was the impetus for today’s expedition: to witness the damage, to gather evidence and to make sure it doesn’t expand. With spears in hand and equipped with GPS, mapping phones, cameras and a drone, over 50 A’i Cofán Guard members meet with the cattle ranchers and the government park ranger. The mixed group walk towards A’i Cofán land up the hill to monitor the situation.

When parks fail to stop deforestation

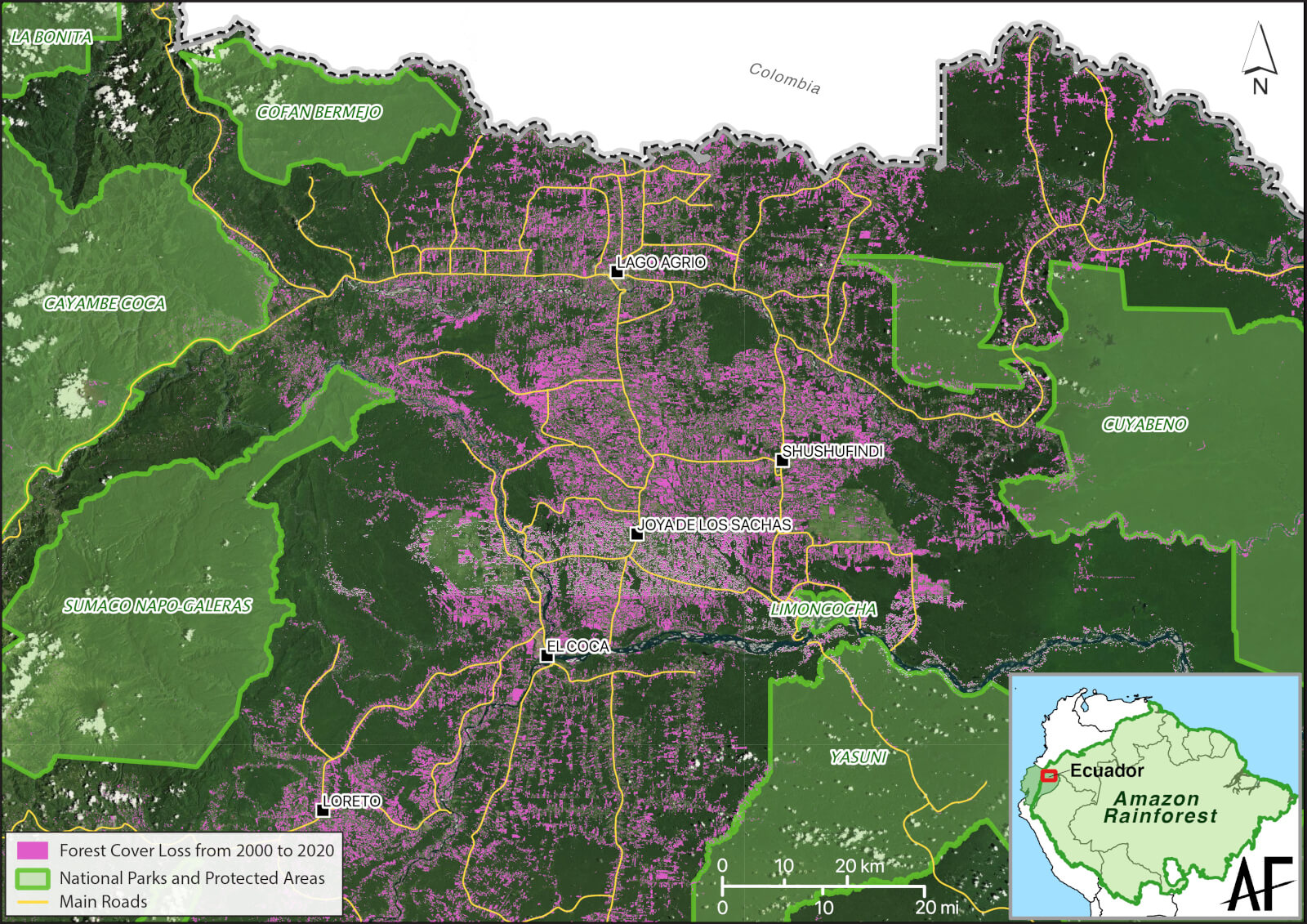

Since the oil industry established itself in the Ecuadorian Amazon in the 1970s, more than 1.6 million acres of primary rainforest have been cleared for oil infrastructure, roads and the colonization that followed. Satellite imagery shows that over 370 000 acres have been cleared in the past 20 years on a 30-mile radius around the oil town of Lago Agrio, where the first oil wells were dug. The oil-driven deforestation frontier has profoundly changed the landscape in the regions of Sucumbíos and Orellana, eradicating thousands of endemic animal and plant species, and displacing Indigenous peoples from their ancestral territories.

The oil town of Lago Agrio has been the epicenter of deforestation in the Ecuadorian Amazon for decades. Despite being surrounded by five large protected areas, this expanding deforestation front is known to be one of the most active in the entire Amazon. Map sources: Hansen/UMD/Google/USGS/NASA 2020, MAATE 2022, satellite imagery by ESRI.

Hundreds of pipelines, small and large, surround the town of Lago Agrio and ultimately bring crude oil from the Amazon across the Andes to the Pacific Ocean.

Just outside of this area are five large protected areas, among the most iconic places in Ecuador: Yasuni National Park, Cuyabeno Wildlife Reserve, Sumaco Napo-Galeras National Park, Cofán-Bermejo Ecological Reserve and Cayambe-Coca National Park. These conservation areas, which overlap with Indigenous lands, were designated decades ago by the Ecuadorian Government and promoted internationally as reserves set aside to protect the forest and the carbon they contain.

According to satellite imagery computed by University of Maryland and published by Global Forest Watch (GFW), thousands of acres of forest have been cleared inside the conservation areas over the past decade, especially in areas along the boundaries and near roads.

As the frontlines of colonization and extractivism expand deeper into the forest beyond the original epicenter of Lago Agrio, it is legitimate to ask whether the protected area system set in place by the Ecuadorian Government has succeeded in blocking deforestation and road construction.

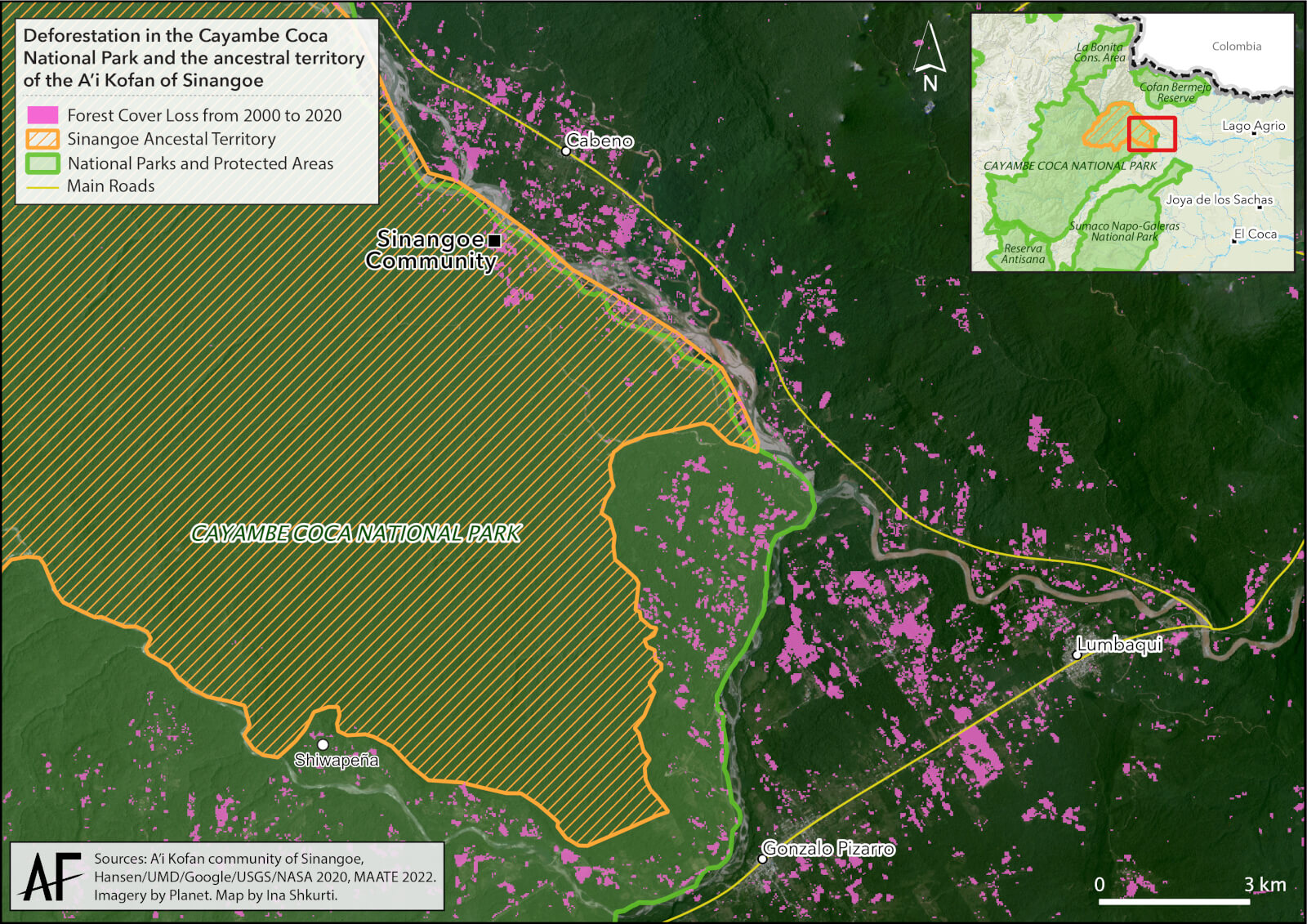

For example, in the valley that surrounds the Due River, satellite imagery shows that over 1 700 acres of intact rainforest have been cleared in the past 20 years, with peak deforestation rates occurring in the past five years. This deforestation has taken place in the first six miles of the park, just outside ancestral A’i Cofán territory. Across the entire National Park, 4 450 acres have been cleared since 2001 according to GFW.

The Cayambe-Coca National Park boundaries have not halted deforestation. More than 4 450 acres of forests have been cleared inside the park since 2000. However, A’i Cofán lands inside the park are still almost 100% pristine.

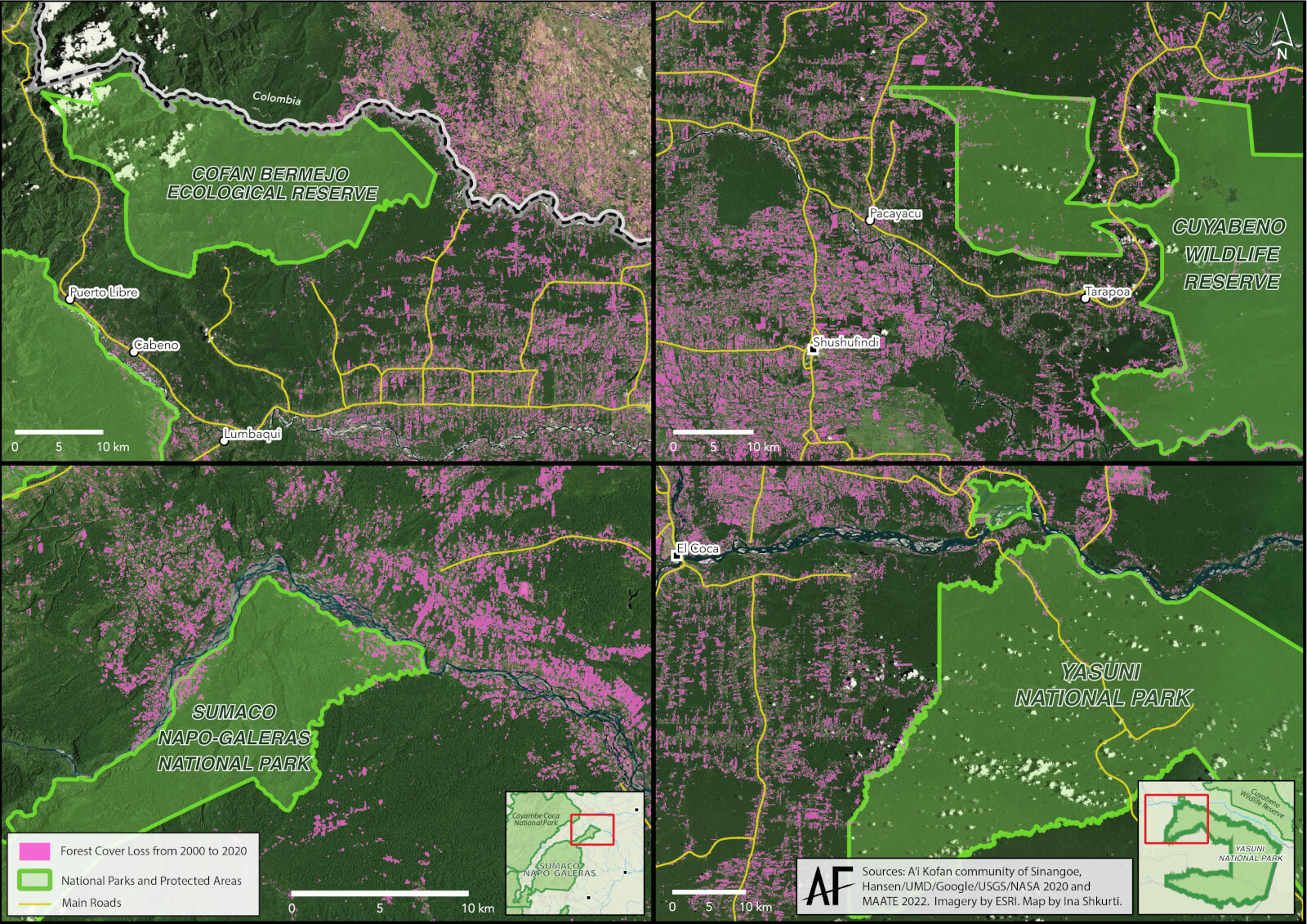

Meanwhile, inside the first six miles of the world-renown Cuyabeno Wildlife Reserve, more than 6 180 acres have been cleared in the past 20 years, with over 40% (2 470 acres) of which was cleared in the past five years. For the entire Wildlife Reserve, Cuyabeno has lost a shocking total of 10 130 acres between 2001 to 2021.

Table 1: Deforestation (in hectares) detected by satellite imagery between 2001 to 2021 and computed by Global Forest Watch

| Protected area | Deforestation within the first 6 miles inside the protected area | Total deforestation inside the protected area |

|---|---|---|

| Cayambe-Coca National Park | 700 | 1800 |

| Cuyabeno Wildlife Reserve | 2500 | 4100 |

| Cofan-Bermejo Ecological Reserve | 65 | 136 |

| Sumaco Napo-Galeras National Park | 445 | 846 |

| Yasuni National Park | 780 | 2060 |

| TOTAL | 4490 | 8942 |

With the exception of the Cofán-Bermejo Ecological Reserve, all four other protected areas show large tracts of deforestation inside the first miles from their “protected” boundaries. Overall, what satellite images of the Ecuadorian Amazon show is that boundaries set by the government for protected areas are not stopping the unfolding wave of deforestation and colonization triggered by the oil industry more than 50 years ago, and that the ministry in charge of safeguarding biodiversity has failed to prioritize forest conservation and monitoring.

Deforestation from 2000 to 2020 detected by satellite imagery inside four protected areas of the Ecuadorian Amazon: Cuyabeno Wildlife Reserve, Sumaco Napo-Galeras National Park, Yasuni National Park and Cofán-Bermejo Ecological Reserve

Park rangers vs Indigenous Guards

Back in the territory of the A’i Cofán of Sinangoe, the guard is documenting and mapping the deforested plot cleared by the cattle ranchers, using a drone to capture the extent of the damage. Despite the active land clearing for pasture inside the park, it is the first time that the colonos trespass into A’i Cofán land, and Sinangoe’s guard is intent on making sure it is the last. The community is deeply committed to protecting their ancestral territory and the guard has successfully halted invasions and evicted trespassers, not to mention blocking a gold mining boom at the headwaters of the Aguarico River, on the other side of their land. They know their territory intimately and they profoundly care for its protection.

A Cofan land patrol cross a recently deforested patch inside the Cayambe-Coca National Park in order to reach their ancestral land up the hill

On the other hand, the park rangers hired by the Ministry of the Environment, Water and Ecological Transition (MAATE) have very limited knowledge of and contact with the land. According to the ranger accompanying this field visit, the area has not been monitored by the MAATE in over two years, and had the A’i Cofán Guard not detected the illegal clearing, no one from the government would have known about it. This situation is not unique to the Cayambe-Coca National park. In fact, the MAATE’s budget for park surveillance has significantly dropped in the past years, and staff have been drastically reduced during the pandemic, with more than 190 park rangers and managers losing their job on a single day in 2020.

While threats to biodiversity, Indigenous lands and the global climate rapidly increase, the government response has been to reduce its capacity to monitor and control those threats.

Indigenous peoples are the real stewards of the Amazon

There is scientific consensus, including in the latest IPCC mitigation report, that one of the most effective and efficient ways to tackle both the climate and biodiversity crises is by protecting large areas of intact wilderness and recognizing and enforcing the rights of Indigenous peoples, especially in the tropics where both carbon and species are found in extreme abundance. In the Amazon, where hundreds of thousands of hectares of forests are lost every year due to large- and small-scale agriculture, oil extraction, gold mining and road building, the international community is ramping up its efforts to support Amazonian Nations in their conservation efforts.

Sinangoe’s grassroots organizing in defense of their ancestral territory was recognized by the 2022 Goldman Environmental Prize. Photo Courtesy Goldman Environmental Prize

However, there is a growing rift between what’s being said and what’s being done. While “nature-based solutions” and the large-scale protection of rainforests are promoted in theory, the reality in practice and on the ground is quite different. As seen in the case of Ecuador, governments in Amazonian countries are failing to protect forests despite their international commitments and the creation of a national network of protected areas. On the other hand, multiple examples of Indigenous land defense strategies have shown to be highly effective at blocking deforestation and preserving biological and cultural conservation. The example of the Cofán people of Sinangoe, whose ancestral land is entirely inside the Cayambe-Coca National Park, couldn’t be more striking. In a further step towards permanently protecting their territory, Sinangoe delivered their land title claim last year with the hopes of paving the way for other Indigenous nations in Ecuador trapped within the same colonial legal frameworks.

Strengthening Indigenous autonomy and guardianship is at the core of our work at Amazon Frontlines. However, hundreds of communities across the Amazon are still facing the biggest threats to their land without their rights being respected nor their needs for support being answered. To tackle both the biodiversity and climate crises, the real stewards of the Amazon will need to be supported and listened to.