In our world, who gets to speak and who is spoken for? Whose stories are told and whose are silenced?

For too long, Indigenous communities have faced vicious levels of colonial violence, justified through racism, supremacy and the imposition of “civilization”. This violence continues to this day across many spheres and one area where it is particularly visible is in the mainstream media. Indigenous voices, perspectives and worldviews are routinely ignored or invisibilised, whether on national TV channels or in international newspapers.

This erasure is exacerbated by the fact that Indigenous communicators and leaders continue to face consistent threats to their life and security.

In a world where freedom of speech and expression are constantly threatened by mainstream media, governmental censorship, guidelines of social media and physical violence towards communicators, it is very important to provide and protect platforms reflect the diversity of cosmovisions and shed light on the struggles of Indigenous populations.

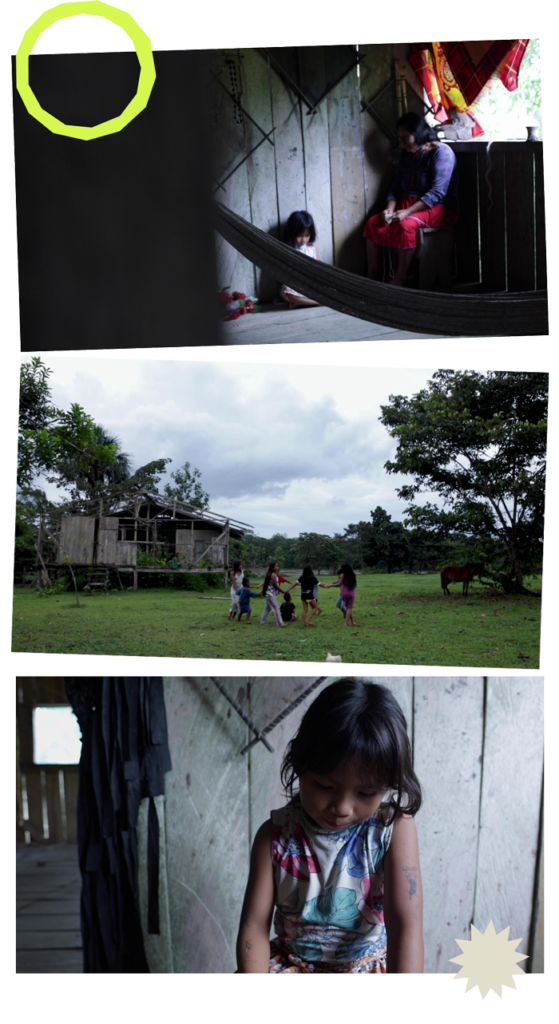

Over the years at Amazon Frontlines and Alianza Ceibo, we have made it one of our core shared priorities to amplify the voices and perspectives of Indigenous communities. Since 2019, we have hosted a Leadership & Storytelling School, training and supporting young Indigenous storytellers. Over the last two years the school has placed particular emphasis on training young Indigenous women storytellers, and on inviting Indigenous artists to lead workshops that can inspire and resonate with younger generations.

Each participant in the school builds up their skills, engages directly with mentors, and develops their own personal projects, working in a range of formats, from documentary film to photography. The school encourages young communicators – from the Siekopai, Siona and A’i Cofán nations – to narrate their lives and cultures on their own terms, drawing inspiration from their ancestral territories.

“Each compañera has complex stories to tell and imagine. They are voices discovering themselves, confronting us, and preserving memories”.

Michelle Gachet, The Storytelling School Coordinator.

As videographer and school coordinator Michelle Gachet explains, ‘For many years, photographers and videographers were hired from big cities and other countries to tell the stories of the Amazon. The voices of people living in Amazon were rarely taken into account. The Storytelling School offers tools to the guardians of the territory -those who know the problems that cross their daily life, those who have grown up listening to their grandparents – so they can have control over the narratives and focus the lens on what is important. Each compañera has complex stories to tell and imagine. They are voices discovering themselves, confronting us, and preserving memories.’

Many of the works produced by young storytellers are first presented in their own communities, before being exhibited in other spaces where they can reach wider audiences. Most recently, in November 2023, the Storytelling School’s latest cohort presented their works at the Gente de Río (Riverfolk) festival, which projected films in various towns across the Upper Amazon. Some of the final projects were also presented at Kanua Festival, the first floating cinema powered entirely by solar energy.

To give you a behind-the-scenes glimpse of some of the incredible students at the Storytelling School, we want to share with you the life stories and creative projects of 7 Amazonian Indigenous women storytellers.

Tamara

Tamara Alvarado is from the A’i Cofán community of Avi’e and is the mother of three children. She made the video clip “Yo también soy” (“I also am”), starring a Cofán boy born in the city who wants to meet his grandfather, a great sage, and seeks to reconnect with his culture and territory.

As Tamara explains,”I want to retell the reality of many Indigenous children who grow up in a place far from their roots for various reasons, such as being able to access quality education, often lacking in Indigenous communities. But these children need to have a connection with the territory, they need to renew their spirit in the rivers, in the waterfalls or by simply understanding life in the rainforest.” Through her work, Tamara wants to bring a message of awareness to both Indigenous and cucamas (non-Indigenous people), for the former “to continue preserving their way of life, worldviews and not lose what our ancestors left for us”.

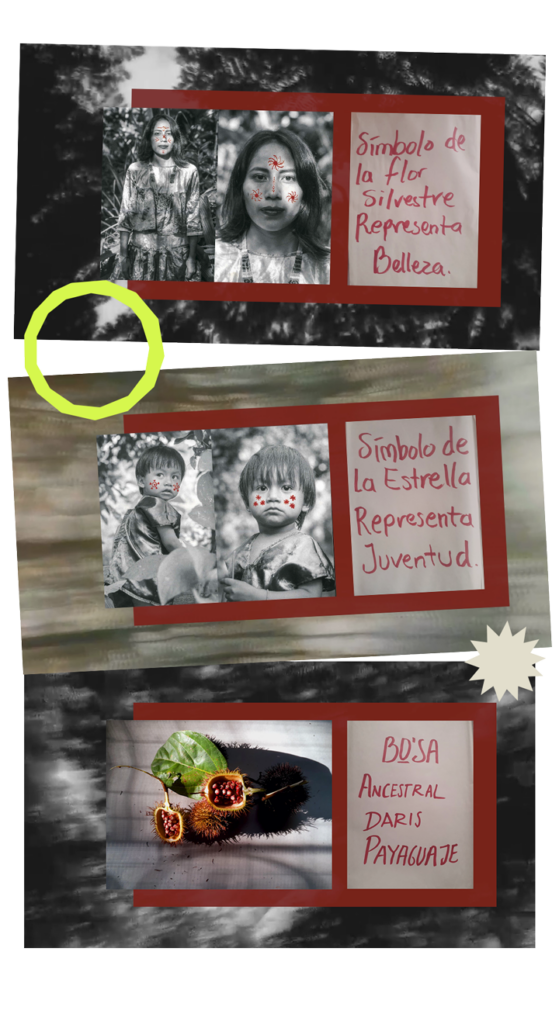

Daris

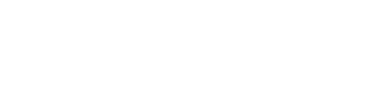

Daris Payaguaje is a 22-year old artist from the Siona Ba’i community of Aboquëhuira who specializes in photography. Her project is called “Bo’sa”, which means achiote. Daris uses the dye-color provided by this fruit to intervene family portraits incorporating ancestral symbols onto the faces.

“In ancient times symbols were representations of beauty, bravery, war or other activities”, Daris explains. “Today they are only painted for important events and ceremonies. It was difficult to find deeper information about the symbols that are painted, since in my generation many traditions like Siona face painting are being lost. I hope that the young people of my nationality will learn, keep it in their memory, ask their grandparents and also pass on to the future generations that we are engaged in constant resistance to colonialism.”

Milena

Milena Piaguaje is a 19-year-old Siekopai young woman from the Secoya Remolino community whose work “Shigra, la memoria de las manos” (Shigra, the memory of hands) is a short fiction film inspired by her coexistence with her grandmother and the knowledge she has passed on to her. The film emerged out of Milena’s desire to reflect on camera how soon there will be very few wise grandmothers left, and how their advice is gradually being lost. For Milena, this process of storytelling is also an opportunity to raise her voice against gender-based violence within communities.

“We women are seen as people who are not able to do anything. Machismo is present, that’s why it’s so important that we as women can have a space to tell our own stories. I have seen how several women are treated badly, which is very painful, so my goal is also to involve more women to join us, so that we can gain strength and tell our own stories.”

Jennifer

Jennifer Yurani Benavides is an Indigenous woman who lives with her son and mother in the Siona Buenavista Indigenous Reserve of Putumayo, surrounded by the richness of nature and the teachings of her elders. Her work is an audio story called “Iti Paiko”, which is about a woman who was born with a great knowledge of traditional medicine. Jennifer wants to revive this story and with it, the knowledge and wisdom of women, exploring their roles and importance for Indigenous peoples and the traces they leave in their daily lives. Jennifer draws inspiration for this work from a sense of awe, explaining that “each story that our elders tell us are new experiences that remain very deep in our lives. These are things that fill you with wonder at every word”.

“As Indigenous women we are protectors and guardians of our cultural values and our territories. We want to tell our stories because we have not really been recognized or valued in our territories. We are vulnerable despite facing mistreatment and discrimination, and we often receive intense spiritual violence. We continue to strengthen our ancestral knowledge and leave traces for the new generations of our territories, so they can see how we have been fighting. We aim to inspire, to strengthen each person so they can: yes we can as Indigenous women”.

Aneth

Aneth Marlene Lusitande Zambrano is 24 years old, from the Siona-Secoya nations and lives in the community of San Victoriano. Her project is a fictional audio story, in which Aneth recreates the myth of the Goddess Rutayo, who would give origin to the Paico’ca language, which allows for Siona and Secoya nationalities to communicate between each other.

“Language is a means that allows us to identify ourselves as a nationality and at the same time helps us communicate with each other. My process involved crafting a myth with my own ideas and imagining the Goddess, describing her physical appearance and arriving at the conflict, where the Goddess gives birth to the language. Through this story, I want to let the world know that the Siona and Sekoya nationalities still maintain their identity through elements such as the ancient Paaikoka language, raise awareness around how important it is to us.”

Morelia

Morelia Mendúa is a young A’i Cofán woman from the community of Sinangoe, who is part of the Sinangoe Indigenous Guard, and specializes in video. Her work is a short documentary called “Ki’an Pushesû” (Warrior Woman), a portrait of Indigenous leader Alexandra Narváez, the first female Indigenous guard and winner of the international Goldman prize.

In her work, as Mendúa describes, she wants to “show all women that we are capable and strong. We need to raise our voices; we’ve stayed silent long enough.” Reflecting on the school, Morelia reflects that “thanks to the training I was able to do my work and tell the world about it, I had the support of the people and my community, and I am proud to have done it.”

Magdalena

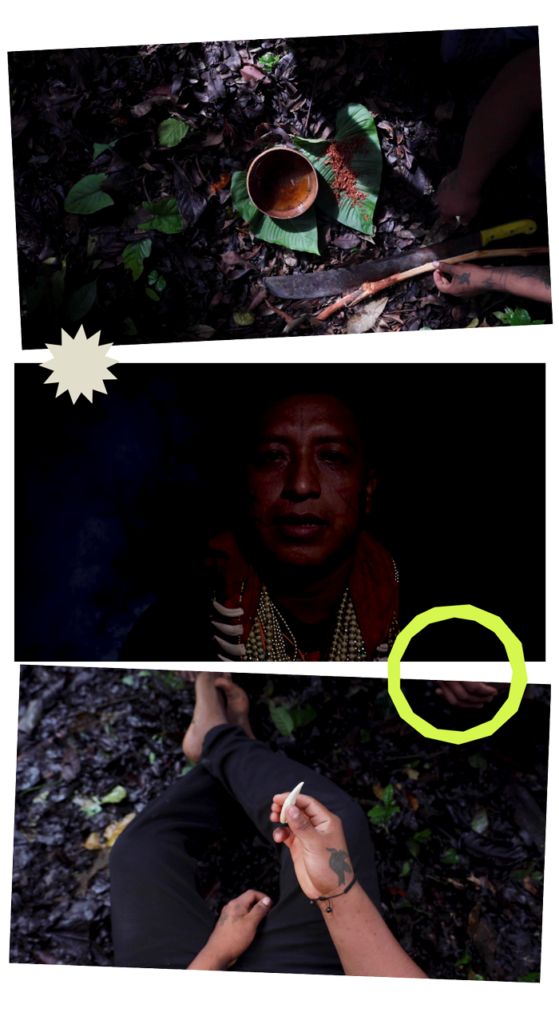

Magdalena Quenamá is an A’i Cofán woman, mother, daughter and sister from the Dureno community. As she describes, her life is the Amazon rainforest, which she loves and which fills her with determination to defend her territory. Her short fiction film is called “Chimindi Ath’epa” (Vision of Chimindi) and is a story about the visions that the shaman has when taking yagé. The shaman teaches these visions – about the past, present and future – to protect the rainforest. To tell her story, Magdalena had the support of her entire family who played the characters in the story.

“With this story I wanted to narrate how important the rainforest is for us. In my community we have many conflicts with oil companies, so I wanted to show other nationalities and communities to take care of their territory. As an Indigenous woman I identify myself with and connect to the rainforest and I want to tell more stories about the community to the outside world so that they know about our existence and the way we live and how we have everything in our territory. I feel proud and happy to have done this work and that it is being exhibited”.