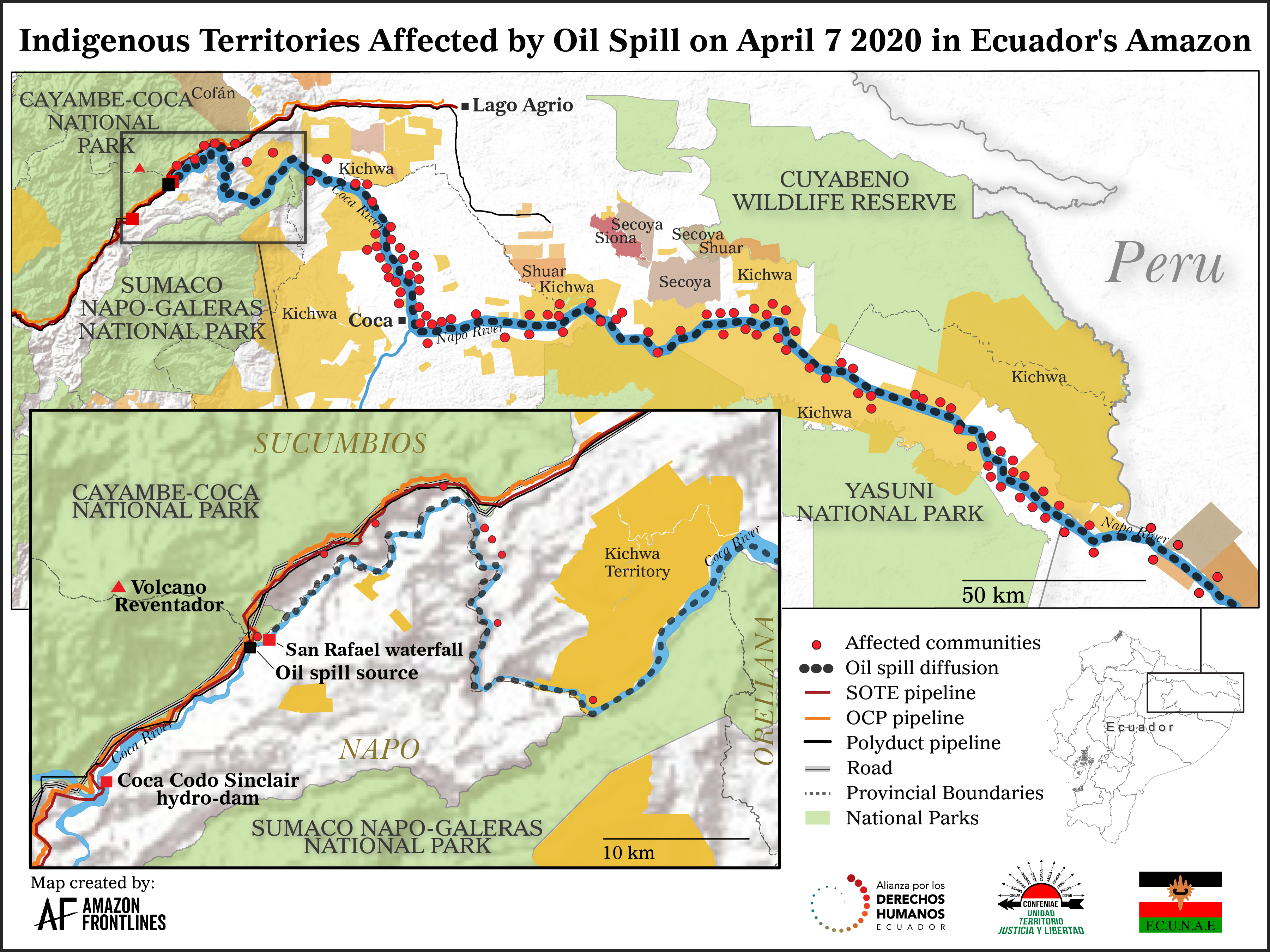

On the 7th of April 2020, the Ecuadorian Amazon experienced its worst oil spill of the past decade. The rupture of two major pipelines and a subsidiary pipeline spilled at least 15,800 barrels of crude oil, polluting pristine ecosystems in one of our planet’s most biodiverse regions, and aggravating an already vulnerable situation for over 120,000 people living downstream from the Coca and Napo rivers. This event was foreseeable and preventable and has triggered dozens of communities and Human Rights organizations to launch a lawsuit against the oil companies and authorities in charge. This blog details how the spill is part of a larger pattern of negligence, impunity and disrespect for indigenous people’s rights and health.

Indigenous People in Ecuador’s Amazon File a Lawsuit in the Wake of Catastrophic Oil Spill. Video created by Amazon Frontlines in collaboration with the Alliance of Human Rights in Ecuador, and indigenous organizations CONFENIAE and FCUNAE

Risky beyond measure

The area is jaw-droppingly beautiful, mountains and jungle criss-crossed by rivers and waterfalls, home to one of the highest concentrations of wildlife on the planet and an important source of water for the biggest watershed on Earth. This is the entryway to the Amazon basin, at the foothills of the Ecuadorian Andes, where rivers rush down the steep slopes of volcanoes, finding their way to the flat plains of the flooded rainforest below. Ironically, the path carved by these rivers rushing to the Amazon is the same one that oil industries have built their tracks upon in order to extract oil from the rainforest and transport it through the Andes to the Pacific Coast some 500 kilometers away, using two pipelines: the 50 year-old Trans-Ecuadorian Oil Pipeline System (known by its Spanish acronym SOTE) and the more recent heavy crude pipeline (operated by the private company OCP, owned by oil giants such as Repsol, Occidental and others). A third smaller pipeline, the Poliducto Shushufindi-Quito, uses the same route to transport gasoline, diesel, liquefied petroleum gas and jet fuel from the Amazon to Quito, the country’s capital.

The gateway to the Amazon, at the foothill of the Andes, is one of the most biodiverse places on Earth, but also a highly unstable area where landslides, volcanic eruptions and earthquakes happen regularly

Building pipelines over the Andes is a high risk venture. In one area along the Coca River, a packed assortment of peaks, steep canyons and valleys have been forged by an epic combination of natural processes that remain volatile. Like a ticking time bomb, these characteristics create the perfect conditions for highly unstable soils and large landslides; which threaten any infrastructure built in the area:

- High volcanic activity: The Reventador volcano, with its main active crater located less than 10 kilometers from the pipelines, has been active periodically, including before the construction of the SOTE pipeline in 1960, during its construction in 1972 (1972-1974) and after (1976, 2002 to the present day). Overall, the pipeline runs close to six risk-prone volcanos;

- High seismic activity: According to environmental impact assessment studies conducted for the OCP, the two main pipelines cross 94 seismic fault lines. In 1987, the area was the epicenter of two major earthquakes that caused large landslides and the rupture of the SOTE along 40 kilometers. Scientists had predicted a 66% probability of a major earthquake occurring in this area for the period 1989-1999;

- Frequent flash floods: Abundant and sporadic rainfall (up to 6000 mm/year), coupled with the shape of the Coca River watershed and steep slopes, often produce flash floods in the area.

Despite risks and warnings from environmental impact assessments, these highly unstable conditions were disregarded as the Ecuadorian government’s desire to export oil from the Amazon to the world’s thirsty markets ultimately won out. A first pipeline, the SOTE, was built in 1972, and despite dozens of major spills since its construction, another pipeline, the OCP, was inaugurated in 2003 using supposedly “cutting-edge technology” but following, nonetheless, the same highly unstable route along the Coca River. Promises were made that no spills would occur, but conditions along the Coca River would change drastically.

How one disaster leads to another

In 2016, the Presidents of Ecuador and China jointly inaugurated the Coca Codo Sinclair hydroelectric dam on the Coca River, right on the foothills of the Reventador Volcano and about 12 kilometers from its active crater. The multi-billion dollar project financed and built by China was supposed to “christen Ecuador’s vast ambitions, solve its energy needs and help lift the small South American country out of poverty,” as the New York Times put it. However, not only did the hydro project never reach full capacity due to over 7600 cracks in its structure, it appears that the dam also triggered an aggressive phenomenon known as headward erosion that led to major changes in the course of the river. This type of erosion is a process by which a river erodes its source region, lengthening its channel in a direction opposite to that of its flow.

Once an iconic attraction for Ecuador, the San Rafael waterfall, the highest in the country at 150 meters, completely vanished in February 2020. Experts link this dramatic event to the construction of the Coca-Codo-Sinclair hydro dam 15 kilometers upriver

By cutting the flow of the river, hydro dams built on rivers with a lot of sediment lead to a drastic drop in sediment load, as was the case for the Coca River. Once the newly low-sediment waters pass the dam, their propensity to cause erosion greatly increases in a well known phenomenon called “hungry waters”. This is what many experts think caused the biggest and most famous waterfall in Ecuador to abruptly disappear on February 2, 2020. Located about 15 kilometers downstream from the Coca-Codo dam, the San Rafael waterfall indeed vanished, but the erosion provoked by the hydro dam didn’t stop there. The hungry waters kept eating away at the river bank until the erosion reached, on April 7, 2020, the site where the three pipelines were buried.

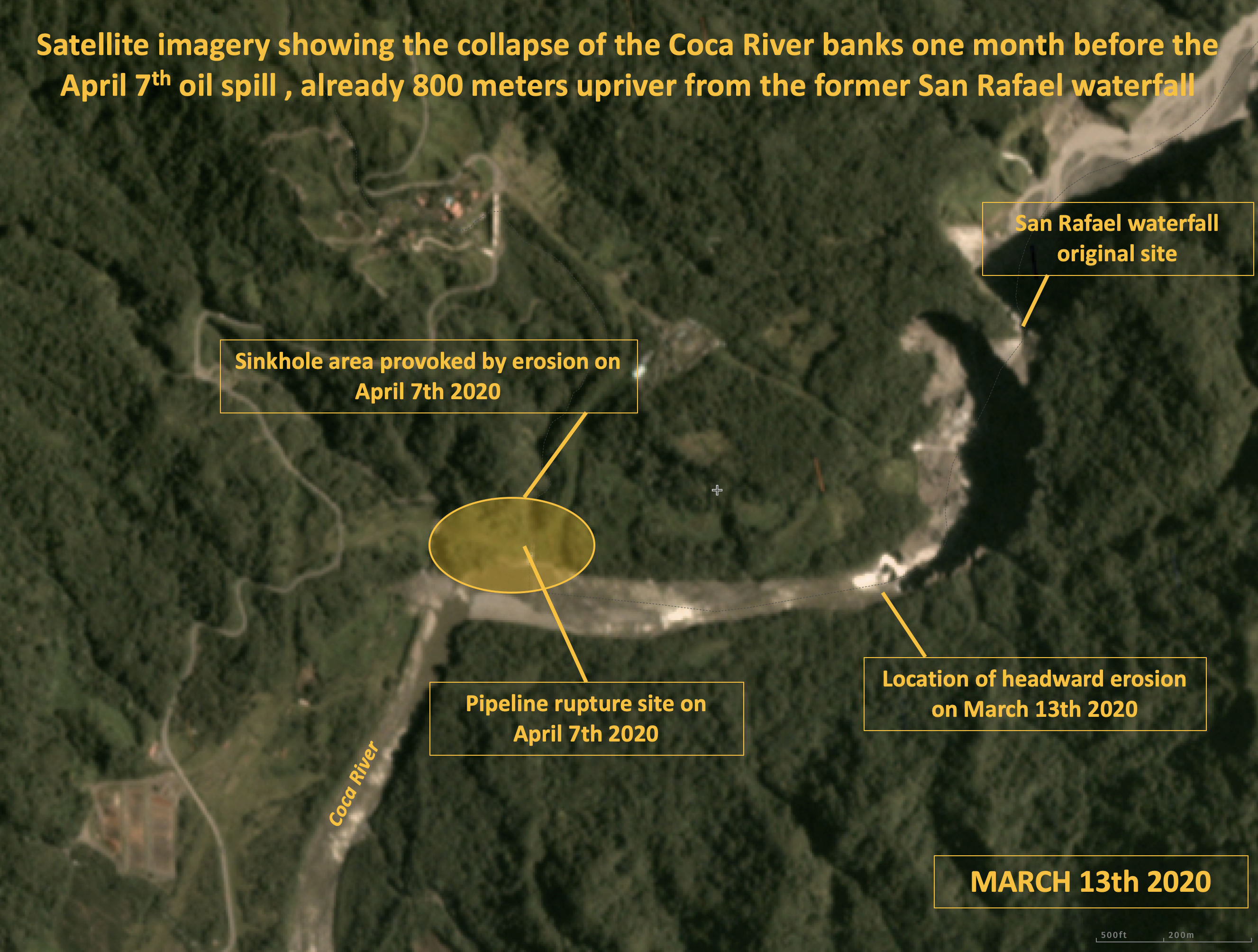

Not only was extreme erosion predicted by experts, but satellite imagery captured a month before the oil spill shows that the collapse of the river banks had already moved 800 meters upriver towards the site where the pipelines crossed the river. The Ecuadorian government and the private company that owned one of the pipelines had plenty of time to prevent the spill and avoid such a disaster, but they did nothing despite multiple warnings and publicly stated commitments to put security measures in place.

Such disasters have happened too many times to be simple accidents. Whether it was negligence or intentional, this disaster was caused by serious omissions of state and private obligations, of which Ecuador has a long track record.

The real price of oil in the Amazon

For the past 50 years, Ecuador has been drilling its jungles for oil in a desperate attempt to boost its economy and repay its crushing international debt. Over the past 15 years, the Ecuadorian government has registered over 4000 new oil wells in 68% of the Amazon, or an average of five new wells drilled every week.

On average, five oil wells have been drilled every week over the past 15 years in the Ecuadorian Amazon

With so many oil wells, platforms and pipelines crisscrossing the Amazon, one would think that Ecuador is an oil superpower, when, in fact, the country’s annual oil production barely supplies the equivalent of two days of global oil consumption, out of which over 46% is exported to the US. However, despite such a small amount of extracted oil, the consequences on the environment and local indigenous communities have been disastrous.

From 2010 to 2019, public and private companies extracted over 1,92 billions barrels of oil from the Ecuadorian Amazon, the equivalent of 21 days of global oil consumption.

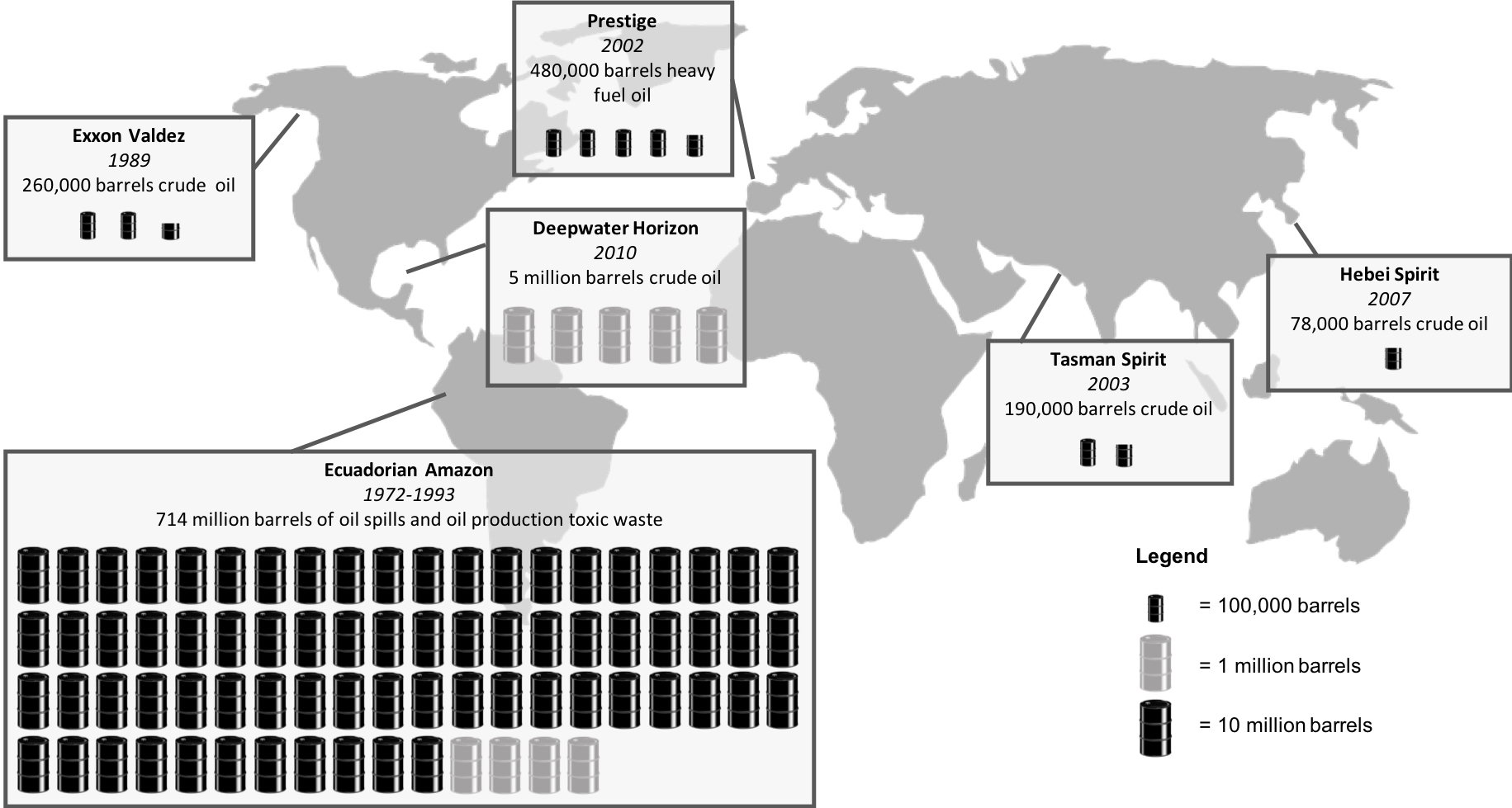

Ecuador has a terrible track record of oil spills due to the damaging practices first employed by Chevron (previously known as Texaco) and then by others in the Amazon. There were an estimated 714 million barrels of oil and toxic waste water dumped into the environment from 1971 to 1993. There have also been multiple pipeline ruptures throughout this era. According to national Ecuadorian news sources, the SOTE pipeline ruptured 47 times from its inauguration date in 1972 to 2003, when the OCP pipeline was installed.

Source: Amazon Frontlines

Other than the OCP and SOTE, hundreds of smaller pipelines also crisscross the far-reaching corners of the jungle. According to Ecuador’s Environment Ministry, more than 1169 oil spills were officially reported from 2005 to 2015 in Ecuador, out of which 81% (952) occurred in the Amazon region. No compiled data has been made public by the government since, so many spills have never been publicly reported.

The end of impunity

For decades, indigenous communities have been the direct victims of the reckless extraction of the oil sector, whose disregard for the environment and failure to take responsibility for its negligence has created a monumental calamity. From the first well drilled in the 1970’s to the latest spill in April 2020, the industry has shown countless times that the Amazon, our world’s most important rainforest, is not an environment fit for oil drilling and pipelines. Unfortunately, the consequences of such irresponsible exploitation is not expressed in dollars, action shares or electoral votes. On the contrary, the impacts are measured by cancer rates, biodiversity loss, toxic loads in fish and medicinal plants, the destruction and contamination of indigenous rainforest homelands, the loss of ancient cultures, traditions and wisdom, and so much more.

On April 7, 2020, at least 15,800 barrels of oil went rushing down the Coca and Napo rivers, spoiling more than 70 kilometers of riverbanks inside protected areas and directly affecting over 105 communities, especially those of the Kichwa Nation. Photo Telmo Ibarburu

A month after the spill, the pipelines have now been rebuilt and the oil flow re-established, even as global oil prices crashed to historic lows and producers around the world scrambled to deal with an enormous excess of oil. Furthermore, the voices of countless indigenous communities have not been heard; the damages to the ecosystem have not been accounted for; and, the contamination of the vital Amazonian food chain has not been addressed. This is why Amazon Frontlines, along with other Human Rights organizations, is supporting communities with a lawsuit against the Ecuadorian government and the oil companies responsible for this latest spill. It is not going to be an easy battle, but the time has come to put a stop to impunity, and for companies and governments to invest in prevention and pay for past damages. Together, we must look towards a post-extractive future.

Help us hold Ecuador and the oil companies accountable by amplifying indigenous communities’ call for #JusticefortheAmazon.