By Milena Piaguaje and Michelle Gachet

–Can you teach me how to pronounce Pë’këya?

English Translation

Pë … kë … ya, Pë’këya means river of the lizard, because “pë” just the word “pë” itself is lizard, so we say Pë’këya.

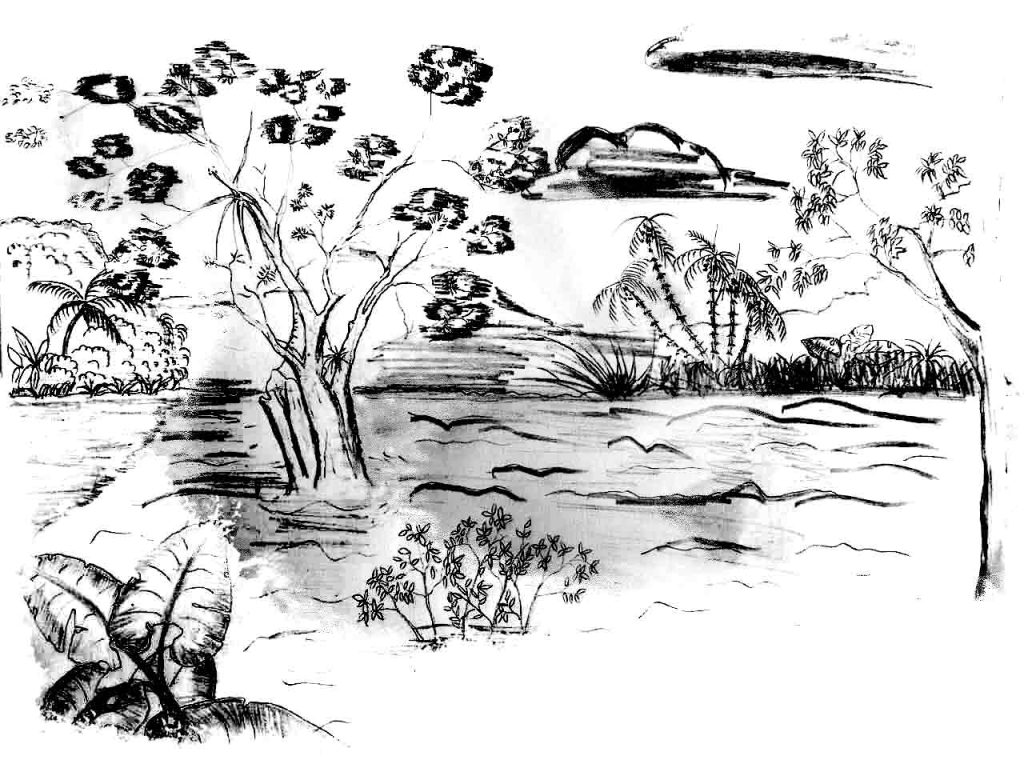

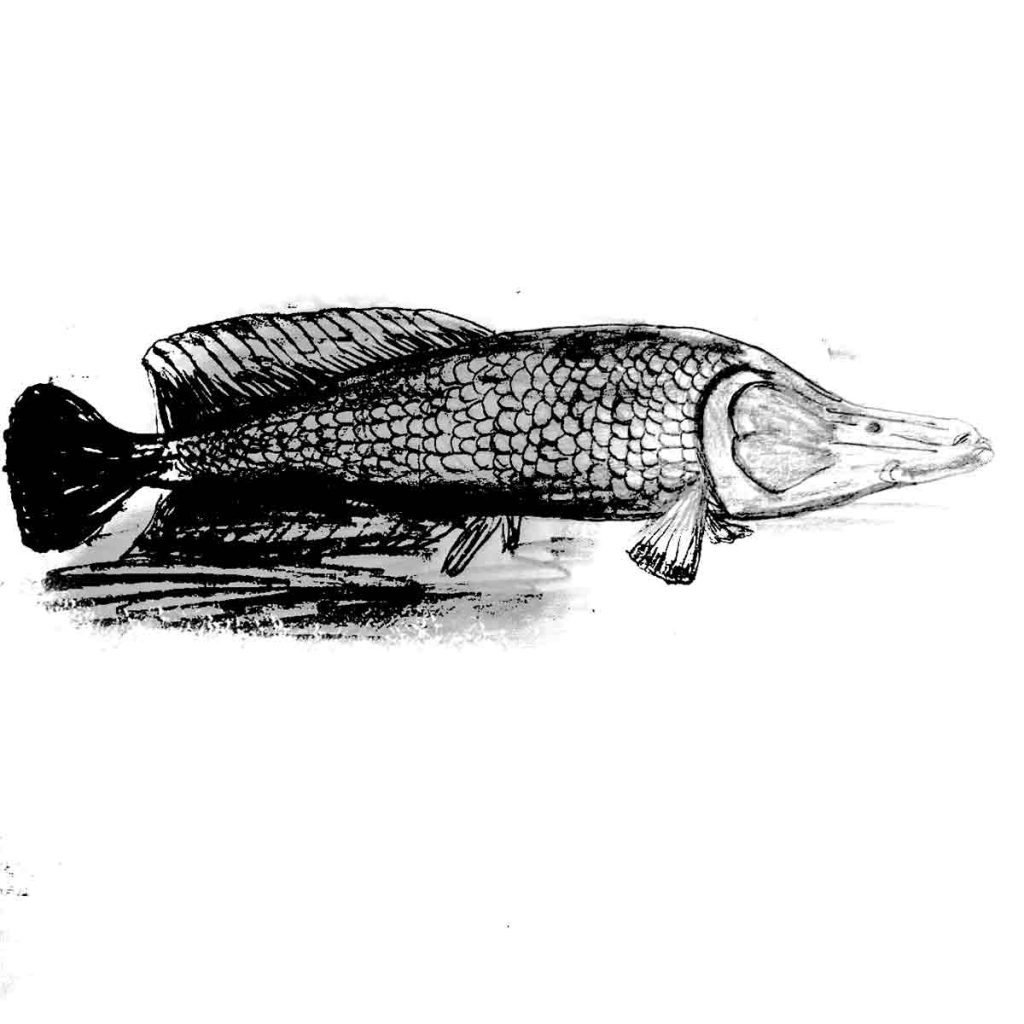

As a child, Siekopai youth leader Milena Piaguaje believed her ancestral territory could only be reached through the visions of yagé (ayahuasca). Then, one day, during a long canoe journey, her mother woke her and her three siblings—they had arrived at Pë’këya, the sacred home of their people on the Ecuador-Peru border. Here, the dark waters of the lagoons merged with the green currents of the Aguarico River, concealing alligators, tree roots, and an entire hidden aquatic world.

–Take me with you on your first trip to Pë’këya…

English Translation

My dad took us and we went around through the Napo River. We arrived at the exact point to enter the mouth of the river, to Pë’këya. We were about to enter the community of Mañoko. I was asleep, with all my siblings… and my mother said: “get up, children”. She named me, my sister, everyone, and she said: “we are arriving, we are already here in Pë’këya”. And I said: “wow, what is happening here?” I never said to my mother: “why didn’t you ever tell me that you can get to the territory without taking medicine?” But I kept on thinking, right? In my mind I said, “what time does the queen of the water come out?” I was surprised, seeing the water, the Aguarico River, and the river at the entrance, which is darker, and seeing those aquatic trees. That was different: the plants. Then I remember that I felt more alive at that moment. I felt I had that connection with the earth.

–What was it like to meet your family for the first time?

English Translation

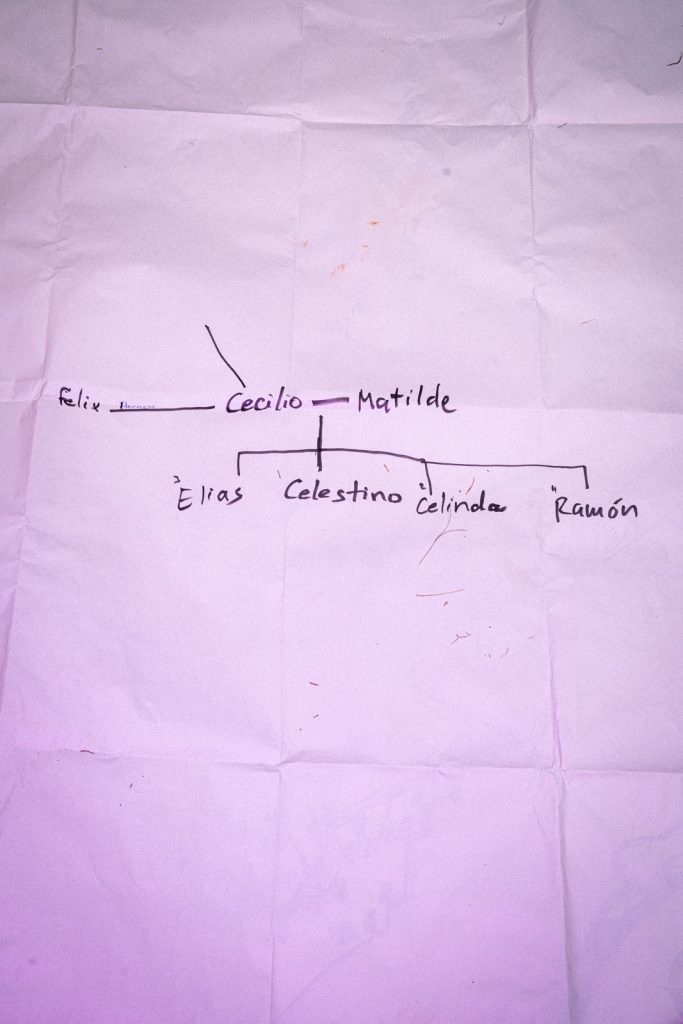

I remember arriving in the community and seeing my family there. At the time, I didn’t realize they were my family—I only sensed they were my relatives, as my mom hadn’t explained it to me at that moment. My mom greeted them and then she said, “she is your aunt”. I only knew there was one aunt, but from then on almost everyone in the community was my family on my mom’s side.

The Siekopai were displaced and dispossessed by the war between Ecuador and Peru, the ambitions of rubber barons, and the pressure of evangelical missionaries.

–What is it like for the Siekopai to live away from their ancestral territory?

English Translation

The elder César said: “We are like the u’kwisi, I don’t know what it is called in Spanish, but we are like the u’kwisi. We had to be dispersed. When you throw u’kwisi on the ground, it grows; it grows in one place, it grows in another place. That is why the elder says: “we are like u’kwisi, we are scattered and dispersed, but we are connected”.

–What does it mean to have been displaced from Pë’këya?

English Translation

The paai (Siekopai people) have always been in Pë’këya. We were all in one place. Sometimes I wonder: if not for the evangelical missionaries and the rubber tappers, how different might things have been? I still believe that we, as women, would have retained the power and gifts passed down from our grandmothers. We were always respected in the world of the paai. Since the arrival of Western colonization, everything has begun to change. That is where machismo comes from too.

–Did you feel different after being there?

English Translation

It makes you think differently, doesn’t it? You understand that concept or the way of thinking of the elders. That’s why they love the territory so much. It made me reflect on why we must keep fighting against the State—for the property title and the right to continue our ancestral practices before our grandparents are no longer with us.

Eighty years later, an entire nation longs to return to their homeland and continue living as Paai—the Siekopai people.

–What future do you imagine for Pëkëya?

English Translation

If we talk about the future, I imagine us, the children, weaving our baskets, making pottery, practicing, drinking medicine in connection with our mother and our god Ñañë Paina. I envision a big maloca house, as we say: “the big house of the Siekopai Nation”. I imagine myself there with the elders, with their wisdom always there with us, accompanying us.

English Translation

I’m happy to step on the territory of my elders but sometimes it makes me sad that, because of the State, we had to divide ourselves. Now we are dispersed. Pë’këya is where my elders drank yagé (ayahuasca). Because of the State, we had to divide ourselves. Now we young people know that Pë’këya is the great house of our elders.

These are the stories, memories, and dreams of Milena, a young Siekopai woman determined to return to her ancestral territory—to bury her baby’s umbilical cord beside those of her ancestors.

English Translation

All my grandparents’ umbilical cords are in Pë’këya territory. When a baby is born, the umbilical cord must be placed next to a tree to ensure the baby grows strong and life flows harmoniously. As I am currently expecting a baby, I would like to put my baby’s umbilical cord there, connecting them to the territory. I want them to be accompanied by their grandparents, with that spirit, with that gift, so they can grow healthy and strong, knowing that Pë’këya is also their home.

This is a tribute and a song for Pë’këya, the ancestral homeland of the Siekopai Nation.

English Translation

The music flows, the feeling flows and you release all the sadness, and happiness arrives. With music, you renew yourself through singing. I think that music is also part of us, isn’t it? The feeling, that feeling that we must express or that we must release. I remember something I like or I remember something sad and I start singing and I flow, it just flows.

Coordination, interview, video and audio: Michelle Gachet | Photos: Michelle Gachet and Milena Piaguaje| Design: Omar T. Bobadilla | Illustrations: Joffre Piaguaje