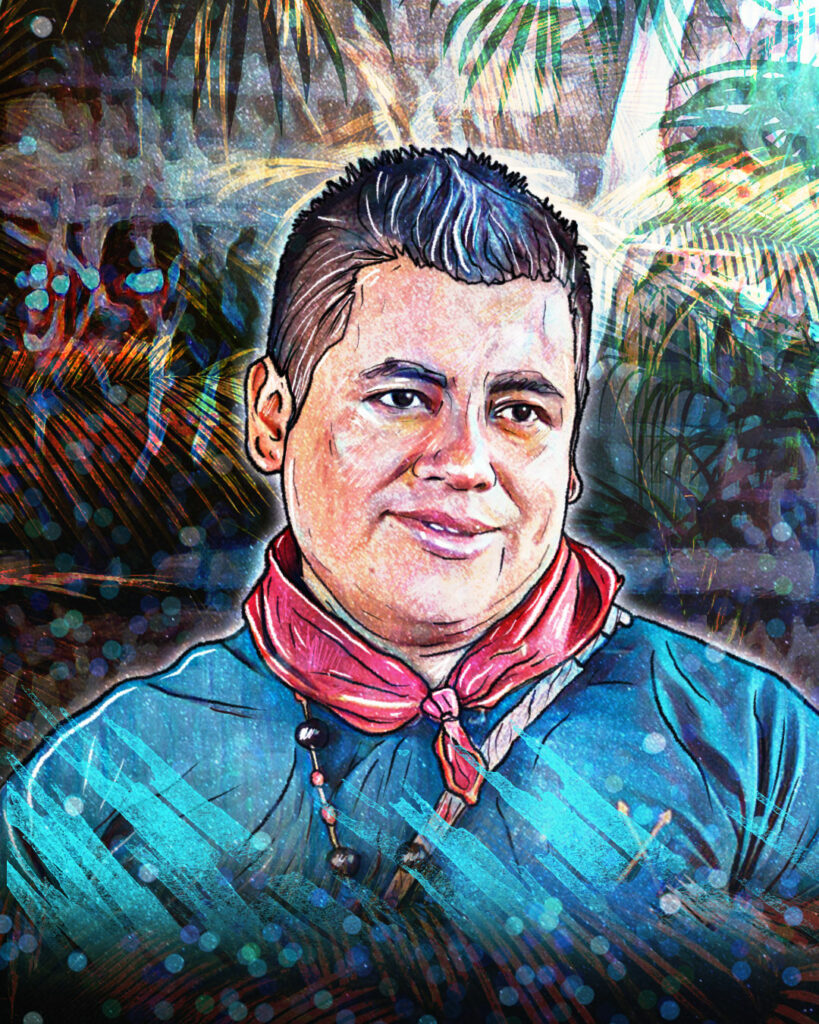

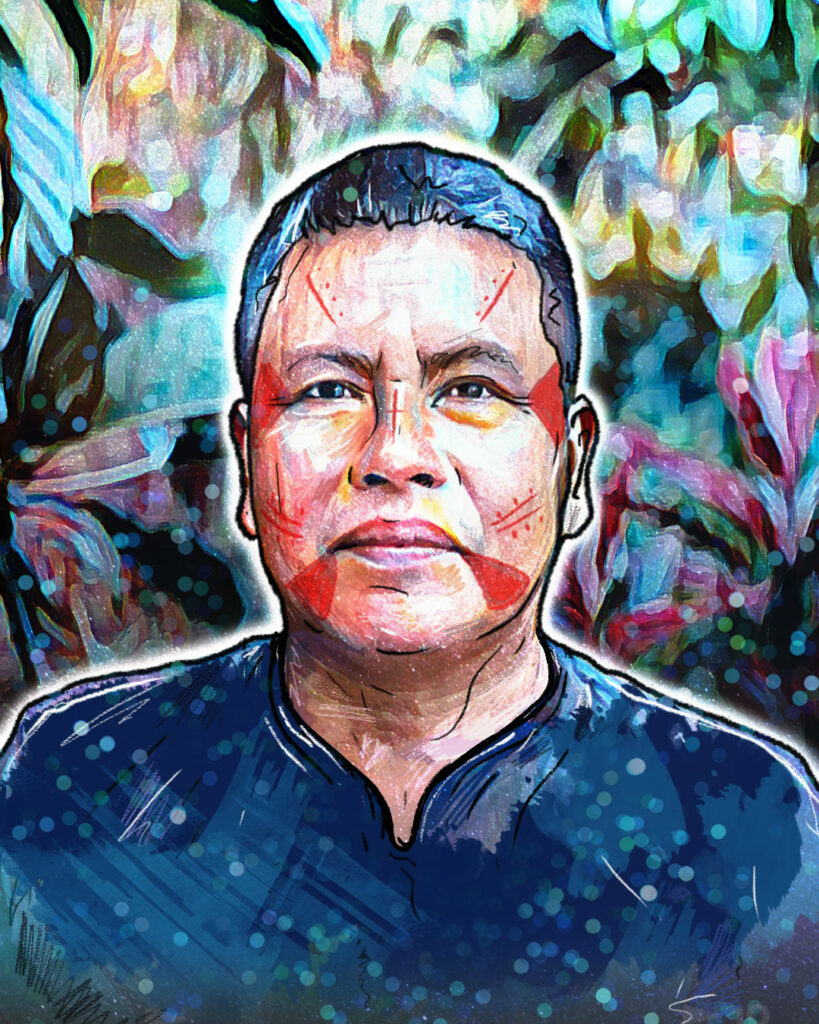

Emeregildo Criollo puts all of his wisdom as an A’i Cofán grandfather into the Sinangoe community’s community-led education process, discovering its challenges and possibilities along the way. Emeregildo is cautious; he dreams of a future with quality education for girls and boys, but he knows that this initiative promoted by Alianza Ceibo and Amazon Frontlines is a slow-cooking dish.

Q: What was the education you received in your childhood and how did it influence your life?

A: In 1973, I studied at the Summer Linguistics Institute – ILV. They taught me to read and write in my own language, in A’inge. I studied to learn Spanish, but I only learned – good morning, good afternoon, where are you going? But in 1993 I was already about 28 years old, and they elected me as president of the community. At that time, the Maxxus company arrived to extract oil near us, but I couldn’t even negotiate with them. They selected me so that I can go study in the United States to learn Spanish and English. I went to Boston where I spent 21 days learning. I came back speaking a decent amount, and now I also speak a decent amount of Spanish.

Q: How did the education provided by the Summer Linguistics Institute contribute or influence your culture and personality?

A: For me as a person, it didn’t affect me. It helped me a lot because they taught me to write in my language. I studied for a year to be a health promoter. They also taught us how to raise chickens, take care of livestock, have family gardens and all that.

But on a cultural level, they are evangelicals. They came to evangelize and they told us that you cannot drink Yoko or Yagé, because that drink is not Christian, it is satanic and that is why people stopped drinking it, but those who are not evangelicals do still drink it.

“We have to look for how to teach so that children learn to read and write in their own language and in Spanish too, that is what we are looking for, but it is still missing because education is not resolved the next day and now, we are looking for it little. little by little.”

Q: What is the difference between the education you received from the SIL and your own education?

A: Community-led education comes from the family and the practices that we Cofans have. My grandmother was my teacher. She taught me how to weave baskets. With her I learned where I can get materials, what size strips I have to split, what size basket I have to make, how many strips I have to have. She taught me the basket first, and then she taught me how to weave Shigra. That is the most difficult. She herself would take me to the mountains to look for Chambira. We would cut Chambira, arrive at the house and extract the fiber. She would cook the Chambira fiber, leave it for three nights and three days in the sun so that the fiber would bleach, and that’s how she taught me the process. After that, we would divide the fiber and then spin. When it finished spinning, she would begin to weave, and that’s where I learned to make Shigra. Likewise, she said that we have to keep the house clean. She said that to have a clean house, you have to have a broom, and she taught us how to weave a broom and to sweep around the house. So we learned how to educate ourselves. Not written, without letters, only in practice; that is self-education, or community-led education.

Q: So that is what one does not learn in regular school. Is that the difference between traditional school and community-led education?

A: Yes, the difference is because when there is already a teacher, children do not learn from the family. When we were children we went to school to learn there, but not to practice weaving shigras, weaving baskets, just to know how to read, write, mathematics, the construction of the school, all that was what Hispanic education brought. But it didn’t change our family practices, the language was not changed, because within our communities we continued to learn.

Q: How has the community-led education proposal been working in the communities?

A: We have been working for more than a year in the A’i Cofán community of Sinangoe, because we did an evaluation with parents throughout the community to understand if the children are learning in their own language or if they are already leaving it behind. Most children hardly speak in A’ingue, but rather in Spanish. We found that this is what was missing, because they do not have any practices of their own.

Now we are creating a curricular framework so that the teachers themselves can apply it, teach in their own language. We are also training about seven commissioners so that they can work with the teachers to put the framework into practice.

Q: Is there an interest in this community-led education proposal being interrelated with conventional state education?

A: That’s my idea. We have to look for how to teach so that children learn to read and write in their own language and also in Spanish. That is what we are looking for, but it is still in process because education cannot be resolved from one day to the other. We are looking for the answers little by little.

Q: Why is it so important to maintain your own language?

A: We as a community have always known that the Kukamas, the Hispanics, are not trying to communicate in our A’ingue language. We – like crazy – are trying to learn Spanish, because otherwise, how can we communicate in order to defend ourselves if these companies enter our territory?

Q: How is the community-education proposal linked to the defense of the territory?

A: In Sinangoe, we started working on territorial defense with the Indigenous guards. We have seen that the school children are also interested in learning to be guards and we are forming a training base for guards, so that as children they learn, by participating and walking in the jungle, what the job of the guard is to defend their territory.

Q: What do you think is the biggest challenge you have right now in implementing community-led education?

A: As a challenge, what we have seen in the communities is that the students in these schools finish primary school and stay there, the young people finish their high school diplomas and stay there, they are paralyzed there. This is a challenge because fathers and mothers do not have the money to send their children to school so that they can finish their high school diploma and move on; that is always difficult in all communities.

Q: Do you think that implementing this community-led education process could improve that reality?

A: With community-led education, you can learn everything about the culture, but to continue on with high school and onwards, I don’t know, we don’t know yet. It is still a process, we have to go little by little, that is why now we are looking to help the teachers too. They also have a long way to go because they have to improve to be able to teach the children. That is why now we are working with Siekopai and Cofans from Sinangoe so that they can continue their studies to be teachers.

Q: Do you hope that this model that you are studying, working and all that, may be accepted by the Ministry of Education as a valid curriculum?

A: The Ministry of Education has to know what we are doing, otherwise it will be a mistake. We are organizing to go and present everything we are working on, which includes our entire curriculum.

“Our hope is that teachers will teach students this community curriculum. That the entire community can say: this is how we want our sons and daughters to be taught.”

Q: Why is it important for the Ministry of Education to approve or understand this?

A: We went directly to Sinangoe to work with the teachers, but they said that without authorization from the Ministry of Education, they could not participate in our workshops or teach what we were working on to the children. From there, we began to request that the Ministry authorize the teachers to participate in the workshops, but there hasn’t been a response. If they abandon the classes to go 3, 4, or 5 days to train, they will be fined, because it hasn’t been authorized by the Ministry.

Q: And have the teachers shown interest in participating, or what has been the response of the teachers to take part in these workshops and learn a little more?

A: Working with them at the beginning was very difficult, because we are not from the Ministry. We promoted this from the Ceibo Alliance and they had almost no interest in working with us in the workshops, but little by little, they began to understand. We explained to them that it is to improve their teaching, that we are trying to help, to have a curriculum so that they can apply it. Now they understand it and now they participate in the workshops.

Q: What is the expected result of this community-led education process with the children?

A: Our hope is that the teachers teach the students this community curriculum, because we are working on this with the entire community, so that the entire community can say: this is how we want our sons and daughters to be taught, and that we want to include to the curriculum so that teachers can apply it with children.

That is our result, because we have the MOSEIB – Model of the Bilingual Intercultural Education System – which says it all, but the school teachers are not applying it. In each workshop we are talking about this so that it doesn’t stay that way.