How Indigenous Youth

Abigail Mukucham

Decided to Fight Against Big Oil

When 21-year-old Abigail Mukucham was first asked to represent her people’s binational organization, she wasn’t sure she’d accept the invitation. The event seemed simple enough: a tour of one of the oldest oil extraction hubs in Ecuador, in the city of Lago Agrio, in the northern Amazon region of Sucumbíos. Lago Agrio is a town that was taken over by the oil industry and is known for the contamination and destruction the extraction brought with it.

But Abigail had never done anything like it before. Along with the Achuar organization, COBNAEP, she would join a group of representatives from organizations like Ceibo Alliance and Amazon Frontlines. They were taking the tour as part of their work together, to strengthen Indigenous resistance against Ecuador’s next oil auction.

Abigail was born in the community of Kapawi, near the border with Peru, and she belongs to two Indigenous cultures; her father is Achuar, and her mother is Shuar. But as a young girl, her connection with her territory was interrupted when she moved to the city of Puyo. Growing up in Puyo and now studying in Riobamba, Abigail didn’t know if she was the right person to represent her organization or take the opportunity to learn more about the movement. After all, she lived in a city, she was a full-time student, and she’d never really thought too often about oil extraction.

With some encouragement from her mother and friends, she decided to go, and when we spoke to Abigail about the experience, she told us about how the tour made her see the threat of oil in a new way.

“It was incredibly rewarding for me to get to understand a reality that is hidden from view,” she told us. “Most people don’t know what’s really going on in Sucumbíos.” Abigail went back home as a new member of the movement that is fighting to keep the oil frontier from expanding into her territory and beyond.

* The Binational Coordinator of the Achuar Nation of Ecuador and Peru

**This interview has been edited for clarity.

“It was incredibly rewarding for me to get to understand a reality that is hidden from view.”

AF: Tell us about the experience step by step—what did you learn?

Abigail: We started by going to the first oil well ever drilled in the area. When we got there, we met with an A’i Cofán man [Ermeregildo Criollo]. He told us about how the oil companies had arrived: He was at his house and heard a loud noise out of nowhere. He said that then people approached and offered them cheese, oil, gasoline, and tuna.

So, the people from the oil company gave them those things, and then they returned home. Once they left, he said the Cofanes started checking to see what they had been given. They smelled the cheese, and at the time, they didn’t know what it was. They thought the cheese smelled very bad . . .

And the only thing the Cofanes took home was the gasoline. Because they had been told it was used to make lamps. So, that’s all they took. And then the oil company set up their operations there, and the Cofanes didn’t have any warning; the oil company just moved in, without communicating or notifying them of what was going to happen.

And he told us that later, many of his relatives died. His children had also died from the contamination. And the ones who have suffered the most are the women, due to uterine cancer and other cancers.

AF: How did you feel, listening to this?

Abigail: I really empathized with his pain because losing people we care about…It’s a terrible thing.

After that, we went to a place with oil wastewater. And they explained to us that all the contaminated water went through this area. Then the man who was guiding us told us to smell the wastewater.

He handed us small glasses, and we began to smell each one. The smell of the water was like something burning; it was so strong, you couldn’t bear to smell it. Some people almost vomited from smelling that.

AF: And you, how did you react to that water?

Abigail: It made my stomach turn. And then my head started hurting a lot. And since the smell was so strong, I felt like I had to drink a lot of water because I couldn’t stand the smell.

AF: Have you ever smelled anything like that before?

Abigail: Maybe. For example, when they pave the streets, it’s a similar smell. But the wastewater smell was much stronger.

“The smell of the water was like something burning; it was so strong, you couldn’t bear to smell it.“

“I saw that oil extraction happens far too close to people’s homes.”

AF: What else did you see?

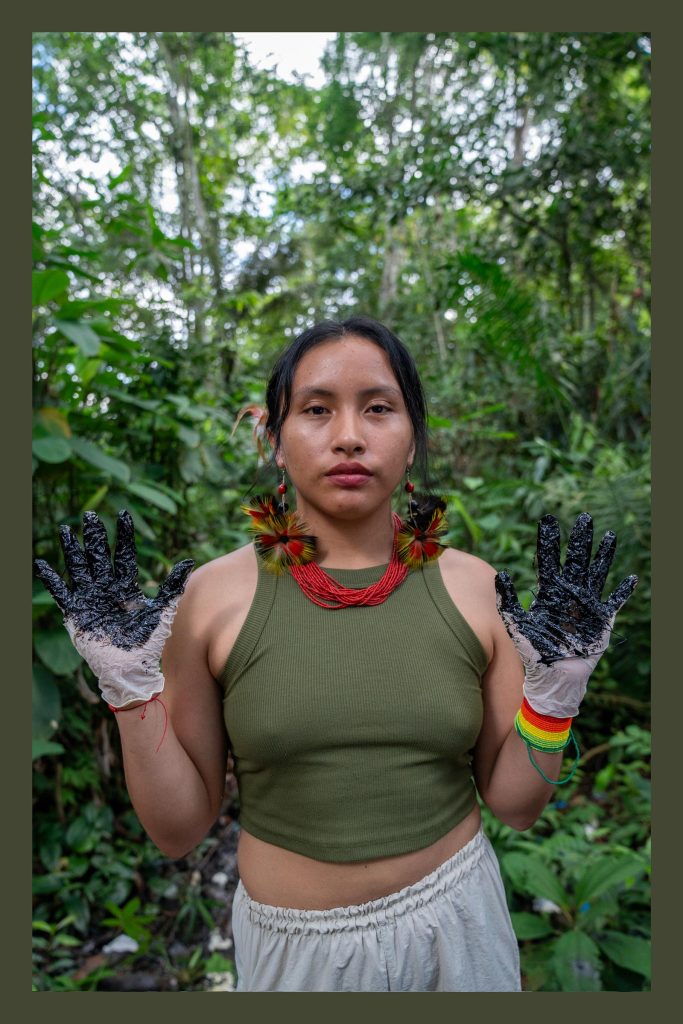

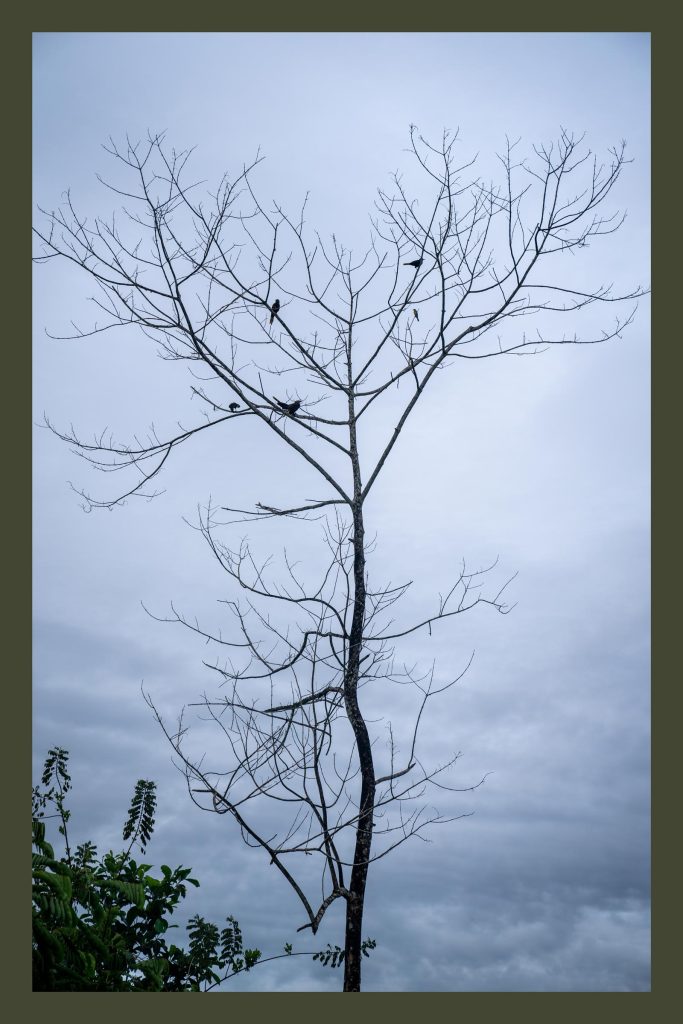

Abigail: As we continued along the path, we came to some abandoned pools. And it didn’t seem at first like there was much oil, because all we saw were plants trying to survive.

It’s incredible how the plants have continued to grow around all that spilled oil. At first, the smell wasn’t so noticeable. But the man told us that this is where they dump all the oil and the other wastes, and as he started moving the wastewater with a stick, the smell became stronger.

Then we put on gloves so we could feel what the oil is like. Its texture was like rubber or silicone, very sticky. They told us not to touch our clothes or our skin afterward because it could be toxic to us, too.

AF: How did you perceive oil before smelling it and feeling these things?

Abigail: Well, when you see it in videos or movies sometimes, it looks like they’re drilling into the earth. So, I used to think oil extraction wasn’t so devastating or so terrible, so to speak, because I thought it took place far from where people live. But on this tour, I saw that oil extraction happens far too close to people’s homes—about 100 feet from where people are living, or less. I was very surprised that the families and all the people who live around the areas where oil is extracted have survived until now. They just cope with the situation and pretend nothing is happening around them for fear of what the State or the oil companies will do to them.

AF: What else did you see, or learn, or what surprised you?

Abigail: On the way back, in the middle of the journey, we came across a pipeline that was on fire. It was lit and burning. I felt scared, since I could see that the pipeline could explode and destroy everyone around it at any moment. Because pipelines run above the houses, not below the ground. What I felt most was extreme fear, anguish, and sadness—all of that.

AF: What kind of fear did you feel?

Abigail: Fear that if we continue to let the State invade our lands, the same thing could happen to us. That our families, our loved ones, could suffer from these kinds of illnesses or any other situation that might arise.

And not just fear. I also felt rage, deep inside myself, because the oil companies have always thought that, because Indigenous people didn’t know certain things, or didn’t speak Spanish, that invading such a community without any information was okay. That’s why I felt rage inside.

“Fear that if we continue to let the State invade our lands […] that our families, our loved ones, could suffer from these kinds of illnesses […] and not just fear. I also felt rage.”

“We must realize what will happen throughout Ecuador if we allow the oil frontier to continue expanding, because we’re all connected.”

AF: From your perspective, what are the key ways to ensure that the oil frontier doesn’t continue to expand in the Amazon?

Abigail: First and foremost, it would be for the Indigenous nations to stand firm against extraction and to say no to oil exploitation.

Oil companies are trying to get into the central Amazon right now. So that’s why there are assemblies being held in each nation to discuss the reality of the situation and to make them aware that if they allow oil extraction to come in, the entire Amazon will be lost. Because Pastaza is at the center of the Amazon and all the provinces are connected.

It would also be good to organize short tours where, for example, young people, students, or people from the cities, like Puyo, even Quito, could be taken to learn about the reality of what people are dealing with in Sucumbíos. That would help people gain another perspective on what’s happening in the Amazon. We must realize what will happen throughout Ecuador if we allow the oil frontier to continue expanding, because we’re all connected.

Credits:

Text: Allison Keeley | Photos: Michelle Gachet | Editors: Allison Keeley, Sophie Pinchetti | Design: Omar T. Bobadilla

Interview Translated from Spanish by Christopher Curran

And thank you to Abigail Mukucham for being so generous with her time!