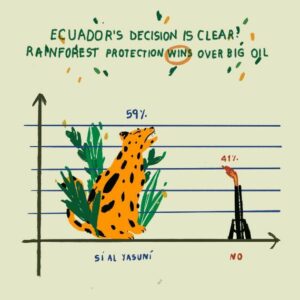

International

Indigenous Women’s Day 2025

Guardians of Ancestral Wisdom

Introduction

“When you find a place to harvest good clay, you know you’ve found a good place to live.”

For the Siekopai women of Ecuador and Peru, ceramics are not just an art. They are integral to the Siekopai’s gastronomy, their medicine, knowledge, storytelling, and cosmovision. And the process of making each ceramic piece—whether a bowl, a clay pot, or a tiesto (a pot to prepare cassava bread) —is vital to transmit the knowledge of its millennial culture across generations of women. But it’s not just about a link to the past; it is also an important tradition for the present, providing women a space to be with each other, strengthen their bonds, and their ability to defend their homes in the Amazon rainforest.

“For us, clay represents territory, women, caring for family, and within it, we are caring for our environment,” says Yadira Ocoguaje, a ceramist and Indigenous leader of the Siekopai nation.

Yadira helped found Keñao, a ceramics collective for Indigenous women supported by Amazon Frontlines, the Ceibo Alliance, and Fundación Raíz-Ecuador-WCS Ecuador. Through Keñao, Yadira helps women revitalize their nation’s traditions. She is also at the forefront of the Siekopai nation’s Land Back movement, which is fighting for the legal title to their ancestral land and to return to their sacred homeland, Pë’këya. The Siekopai are a people on the edge of cultural and physical extinction, with only 2,000 members remaining across two countries. Yadira, like her fellow ceramists, knows that the women in their community are a major key to avoiding that fate.

Revitalizing and continuing the transmission of knowledge and tradition is the first line of defense against cultural disappearance. Without the art of ceramics being carried on and renewed by Indigenous women, the Siekopai and other Indigenous communities would feel their connection to their ancestors dim, and their ability to protect and live in harmony with the rainforest would weaken along with it.

Each time Yadira reaches into the clay, along the river or in the forest, lifts it, feels it, tests it for texture, taste, and smell, she is not simply setting out to mold an object; she’s recovering a piece of her grandmother, Jacinta, a respected ceramist who used to walk through the forest while singing. And she is honoring her grandfather, the great shaman Don Cesáreo Piaguaje, who helped Yadira find her way. She is connecting with the rainforest and with her ancestors. And each time she shares the tradition with others in her community and with the world, she’s building a future where their knowledge and legacies are kept alive thanks to the women guardians of ancestral knowledge.

Know Your Ceramics

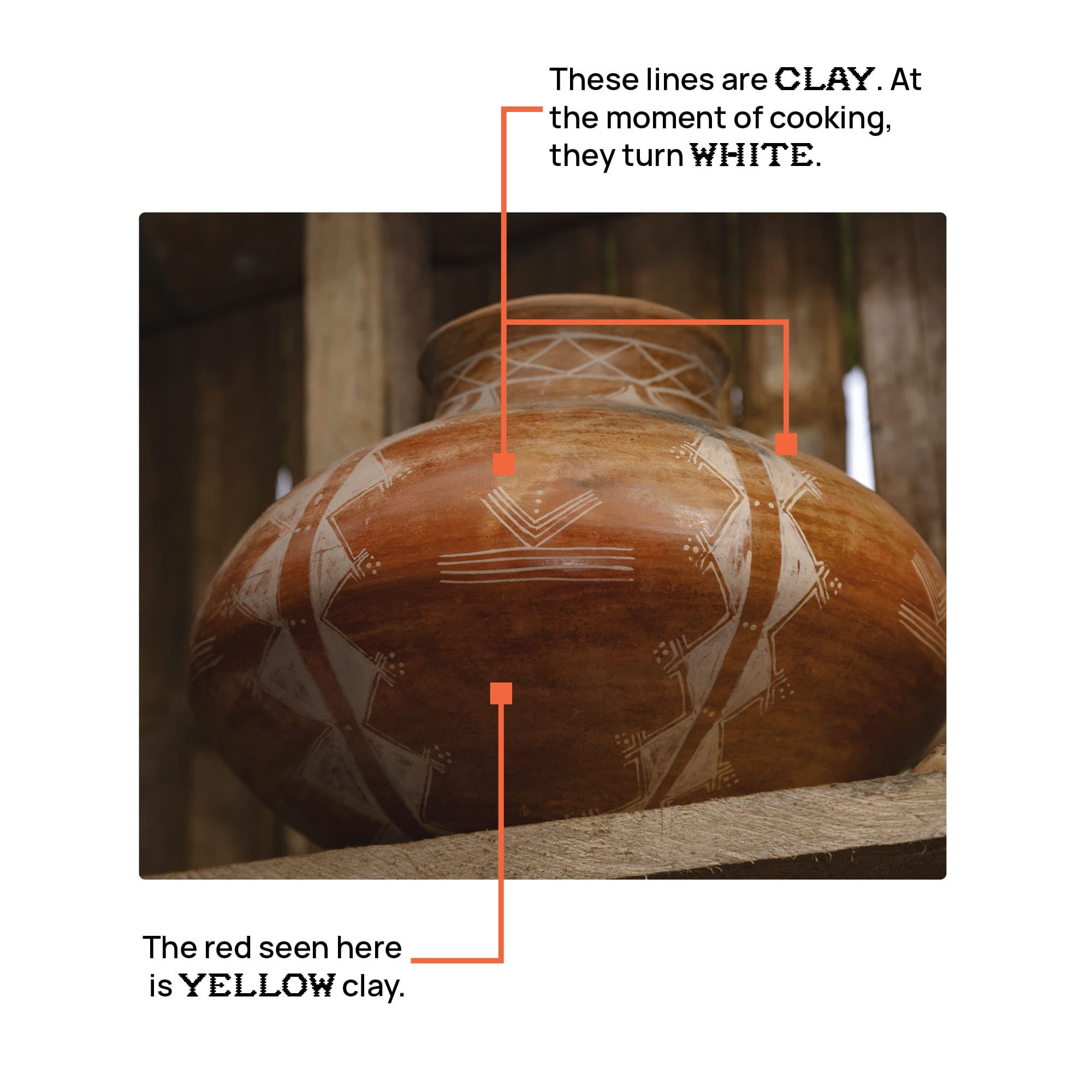

A Map of a Siekopai Ceramic

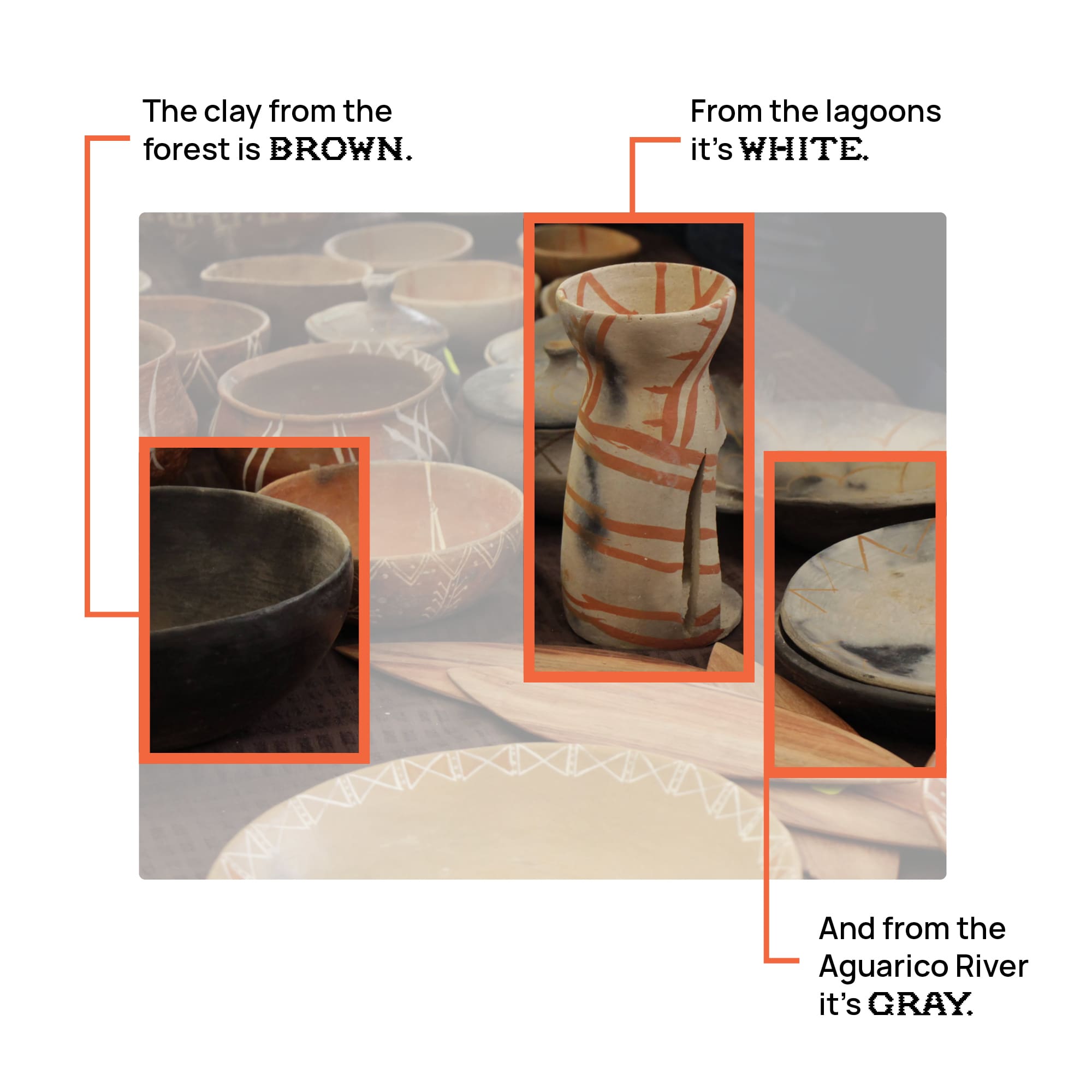

The Siekopai use 3 types of clay in the Amazon

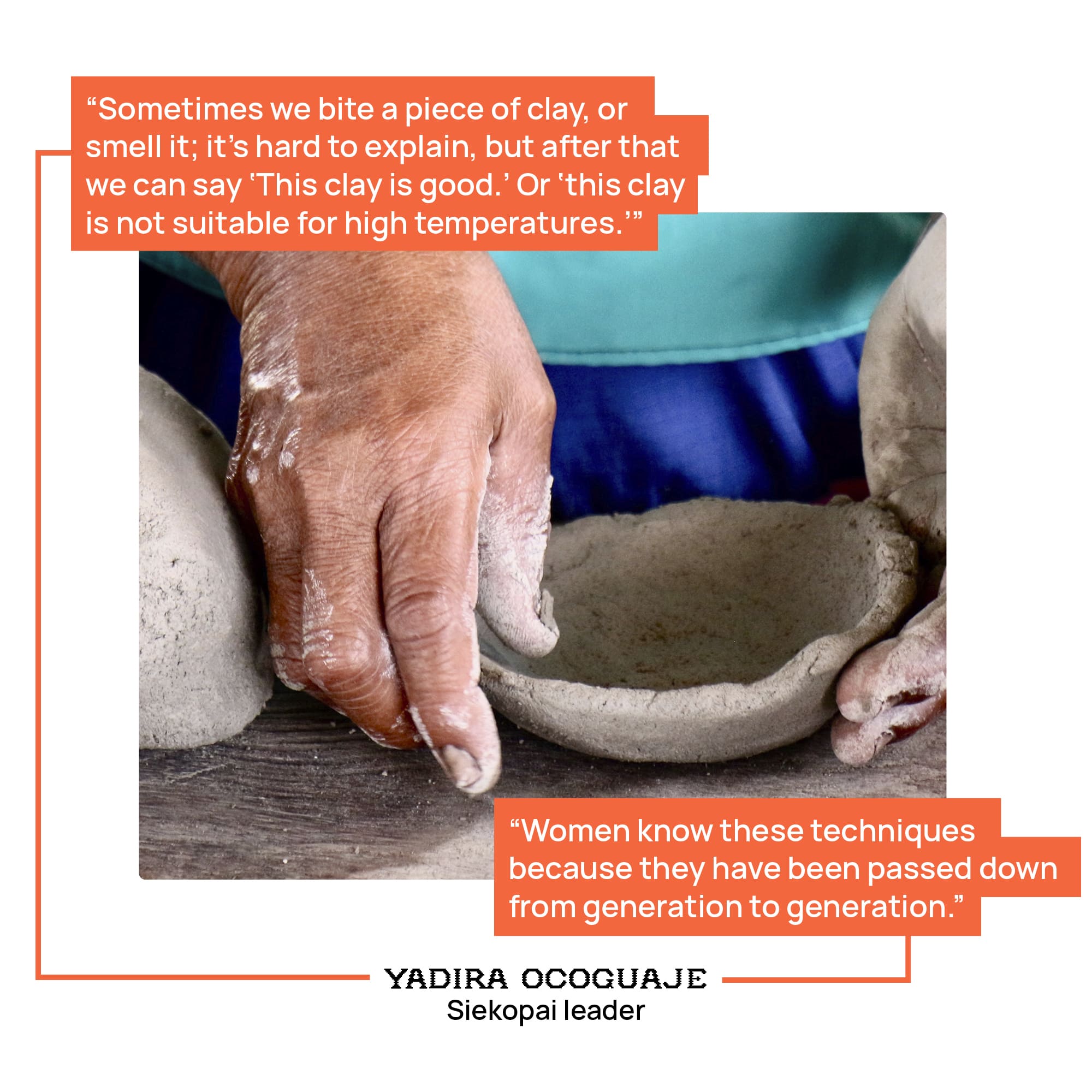

How to Identify Good Clay

The White Lines

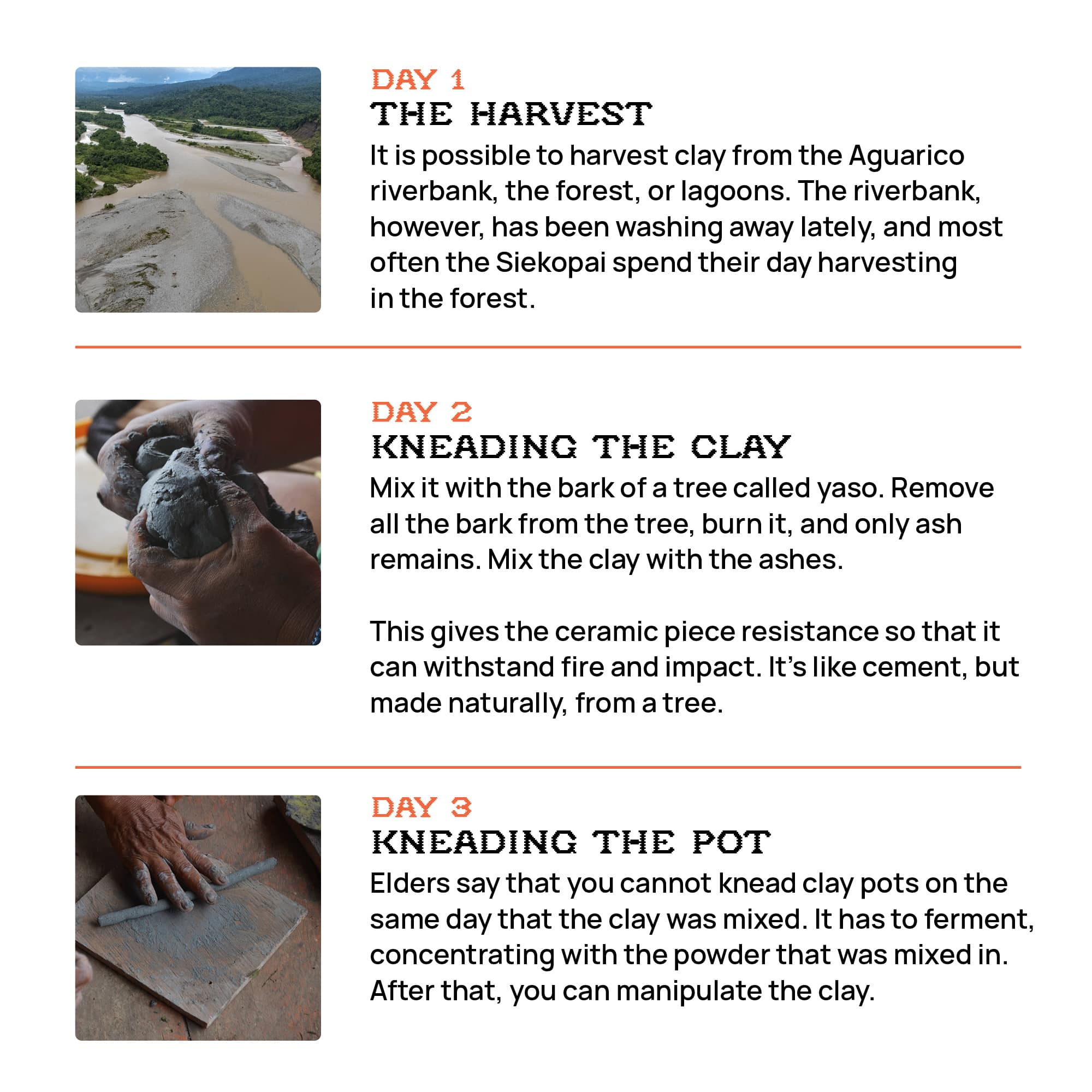

Siekopai Ceramic-Making is a Three Day Process

INTERVIEW

Yadira Ocoguaje, Siekopai leader: Clay is not just Earth or Mud

How making ceramics creates networks of care and protection for women and territories

Yadira Ocoguaje is a young Indigenous leader from the Siekopai nation, guiding her people’s struggle to recover and reunify their ancestral lands in the rainforests of Ecuador and Peru. She is the co-founder of the Keñao Women’s Association and has been recognized for her work in revitalizing ancestral pottery and empowering women in her community. Her efforts reflect her deep commitment to cultural and environmental preservation.

Tell us about the importance of clay and ceramics for the Siekopai people.

In the Siekopai cosmovision, clay is not just a piece of earth or mud. It is a reminder of the struggle our nation has faced since our ancestors. It is about traveling that territory. It’s about exploring and reliving the memory of our grandfathers and grandmothers, who were great walkers and drinkers of yagé [ayahuasca].

For us, clay represents the territory, women, family care, and nature, and through it, a safe environment is created for women that allows us to live in harmony.

Tell us about the special relationship women have with clay.

For us, clay is a woman. In our worldview, Sotowajëo (mother) and Sotowario (daughter), guardians of clay, are the two women who care for the territory. From a young age, we learn that there is a ritual surrounding the making of clay and that all ceramic-making is related to the care of women.

We know that during menstruation, we are stronger and more fertile, and that is the precise moment for making pottery. And during pregnancy, women make clay pots in a position that helps facilitate their delivery. This is all about nurturing a deeply caring relationship, first with each other, as women, and then with the land.

The clay guardians take care of us when we harvest the clay, and their teachings are sacred to us, just like the stories our grandmothers tell us.

When was the first time you heard stories about the guardians?

When I was a little girl, my grandmother Jacinta told me these stories while we were making our clay pots. I think that’s why I always went to her, to listen to those stories and to work the clay with her. Working with my grandmother, she taught me how to perfect my craft.

I liked being with my grandmother because it felt like a safe place for me. She listened to me; she didn’t scold me. If I played with the clay, she didn’t say anything; she let me be creative. And I also liked to harvest with her because she was patient enough to walk with me. If I played, she waited.

And her songs—I liked listening to my grandmother’s songs. I remember that the songs weren’t just memorized; they were also born from that moment. While my grandmother walked, harvested, or wove a clay pot, she sang. When she passed away, everything was gone.

It was as if she had taken all the pottery. Then, one day, my mother and I wanted to make cassava, but we didn’t have any pots. Cassava is made from yuca, grated, and placed in a clay pot. But we didn’t have any, and we wondered, “Where do we make it?”

And since then, you started making pottery with your mother?

Yes, at that moment, my mother and I said, “It’s very important to have this to continue preserving our gastronomy, our food.” Because if we didn’t have those ceramic jars—ceramics used for roasting food—we wouldn’t be eating cassava bread or any kind of dried food. So from the age of 12, I started working with my mother. And it struck me that only the two of us were working on this.

That’s how I met friends who invited me to teach ceramic workshops in the cities of Quito or Lago Agrio, until I created the Keñao Women’s Association. I created it because I thought, “If I continue working outside the community, this knowledge will be lost.”

Can you describe the clay harvesting process and its importance to women?

A typical day of clay harvesting is:

First, we gather and drink yocó, an energy drink that our grandparents have been drinking for many years. We go in a group, each carrying her basket and shigra (a woven bag). Each woman carries her shovel and machete to do this work as well.

And then, we start walking. There are different routes, along the Aguarico River or on foot through the jungle. Once we arrive, the landowner allows us to enter to harvest clay. And there, we always respect our worldview. For example, if a woman is on her period or pregnant, she cannot enter the water.

And that’s where we spend the day. Sometimes the women bring their chicha (a type of juice) or chucula (an ancestral plantain-based drink). And while we’re harvesting clay, we also share not only the chicha, but also knowledge.

What types of knowledge do you share?

In this space, the women sing, laugh, and if a woman has problems, she shares them. If she’s going through a difficult process, it’s also a space to vent. And if a woman feels bad toward another woman, she also opens up to share what’s happening to her.

For us, working with clay is a deeply sacred space. And we always say: “This conversation stays here, it doesn’t leave this space.” If we bring up that conversation outside, we’re breaking our grandmothers’ rules. We have to respect them.

And I think we’re on the right track now because we respect those beliefs, those memories. When we’re finished, each woman takes her clay home, or if we’re harvesting clay for the association, then that’s like a minga (an ancestral community practice of collective work for a common good) for us, and the clay goes to the association.

Do you sell your ceramics?

When a woman makes her ceramic piece, she’s giving all her energy. My grandma used to say, “It’s like when you’re forming life in your womb.” It’s the same when you start kneading a clay pot; you’re giving all your feelings, all your thoughts, because you’re focused on it.

And for me, when a woman gives me a ceramic, it’s incredibly sacred because she made it with so much love, with so much affection, and she’s giving me that ceramic because she gives me all her energy, all her good vibes. It’s difficult for us to sell our ceramic pieces. Many women say, “No, I made it with so much love, and I don’t want my piece to be in hands that don’t value it.”

That’s why we want our ceramic pieces to reach the hands of people who understand our work, and who truly understand the role of women and the energy they put into each piece of ceramics.

At the same time, as women, we’re always looking for alternatives to generate income through various means, so that we’re not just reliant on cutting down trees or planting crops—that’s where everything is lost. And if we destroy the forest, we wouldn’t have anywhere to harvest clay. Then, where would that ancestral knowledge go?

That’s why our grandmothers used to say, “Where there’s good clay, good yocó, that’s a good place to live.” Clay is used to make clay pots to feed the family, and the sacred medicine, yagé, is also cooked in clay pots. We provide for the family in clay pots. Everything is connected to clay, and it also represents a circle of care.

What do you hope for the future of your community, and what role does ceramics play in it?

We want our territory to be in harmony and have a better future, which is why we have formed the Keñao association. We are 26 women, but the work isn’t confined to the association; it’s the Secoya Remolino community, and our work also represents an entire nationality.

Currently, human beings are suffering the consequences of climate change because we lack respect. We are always focused on meeting our needs and forgetting to care for nature. The grandmothers always said that you should only pick what you need to knead a clay pot. You can’t harvest something that you’re going to waste. So, as women, we listen. We are taking care of our clay, and this also means taking care of each other, of women.

Credits:

Text: Erika Castillo and Allison Keeley | Editor: Allison Keeley

Design: Omar T. Bobadilla | Photos: Daris Payaguaje, Michelle Gachet, Nixon Andy and Luke Weiss