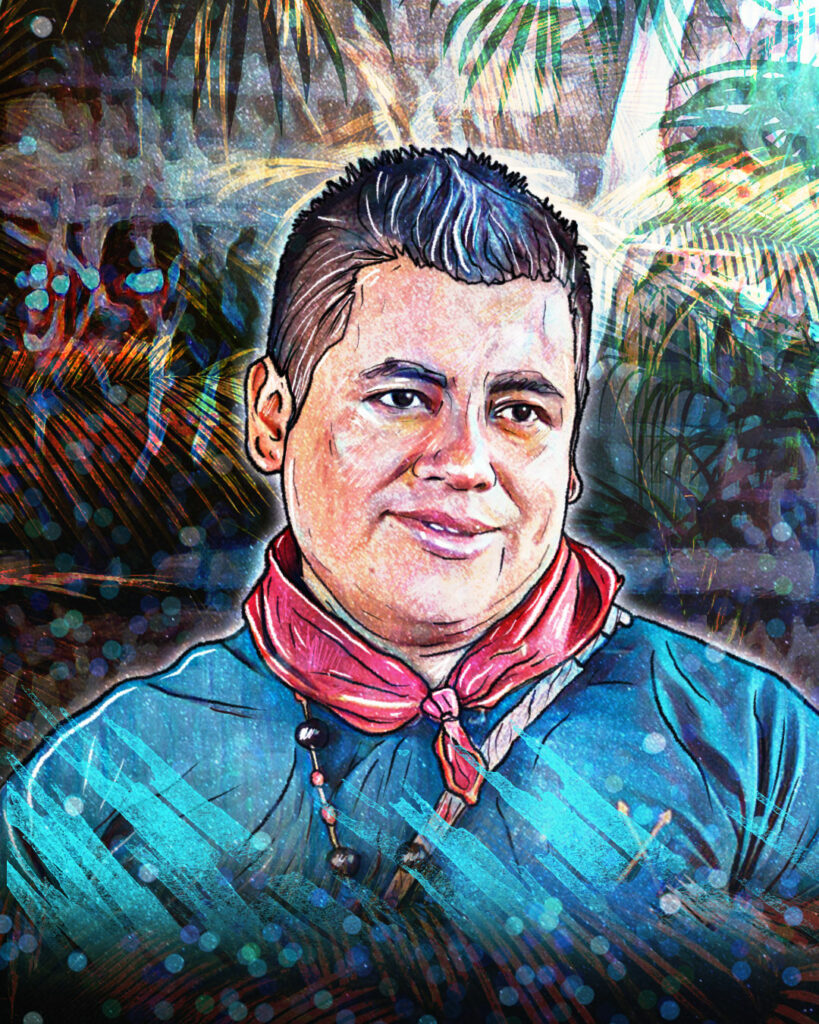

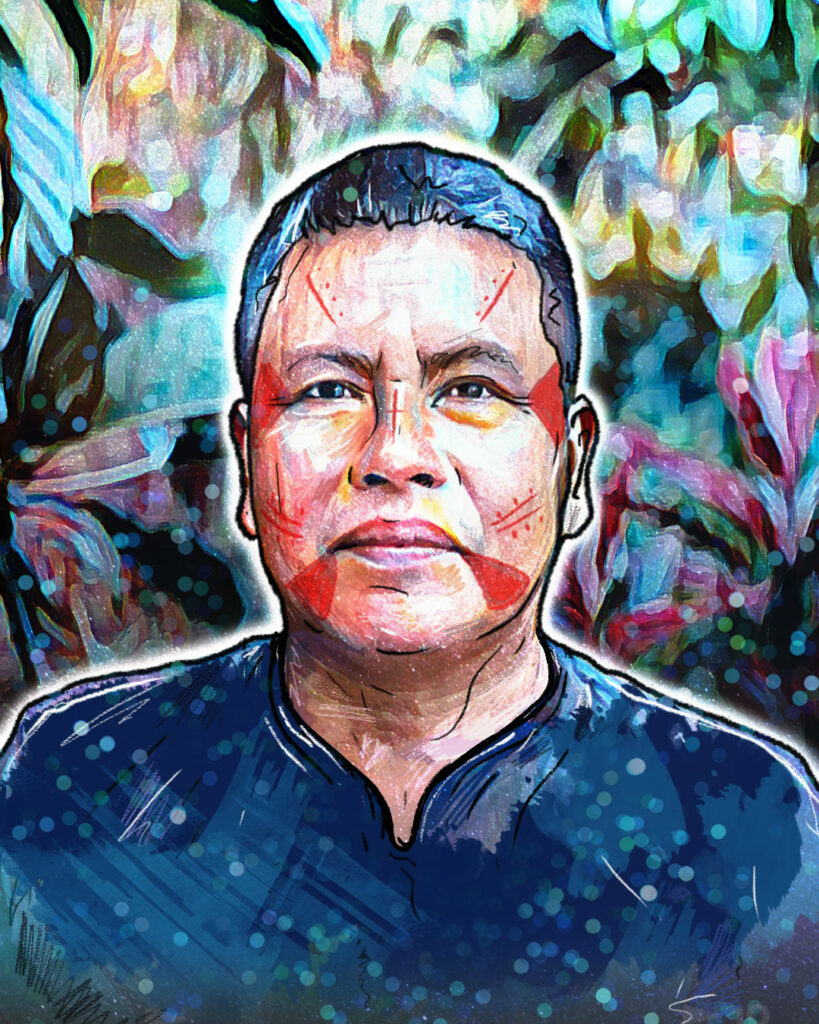

By making a sieve, a child learns mathematics. By recognizing the plants in their territory, children learn botany. By learning, youth are proudly Siekopai: this is how Justino Piaguaje visualizes the future with community-led education, something very distant from his own educational experience, which he explains to us in this interview, as well as the proposal that seeks to guarantee Siekopai cultural survival.

Q: What do you remember about what going to school was like for you?

A: We had a single classroom separated by a curtain. On one side the youngest children, up to third grade, learned in Paaikoka with a teacher from the community, and on the other side the older children learned in Spanish with a Hispanic teacher from Latacunga in the Ecuadorian mountains.

I still spoke in Paaikoka, but I learned to say hello, I asked permission to go out, make some sentences, the basic things in Spanish until I finished school. I remember that they taught us geography, history and all these topics linked to national history such as the discovery of America, of the Amazon by Francisco de Orellana, but no stories of the Siekopai. Rather all those stories I learned at home with my grandmother.

Q: How did you go to school and what was your experience like?

A: A missionary from the Summer Linguistic Institute (SIL) wanted to play Chinese checkers. I knew how to play very well since I was little. We played: I beat him, in the rematch he beat me and in the tiebreaker I won. Then he asked me, do you want to study at school? I told him that we had no money, we had to pay for boarding school and the uniform; My father separated from my mother, so we were alone and did not have the resources. He told me – I support you – he did it for three years and after that the priests of the Capuchin mission helped me.

The school was quite difficult for me, that is, I did not know how to speak Spanish more than what was necessary. I spoke in my language. I thought that everyone knew how to speak Paaikoka, so I was surprised that some spoke Spanish, others spoke Kichwa and others Shuar. Spanish was the language of interrelation. They also taught us Kichwa, that’s how I learned and continued with my studies until high school.

Q: Do you think that the education you received during your time at school affected your culture in some way?

A: There was a kind of interethnic racial discrimination, like the Kichwas felt superior to the Siekopai, they began to make fun of our language, they treated us like cushmas because of our tunic. Of course one feels humiliated, discriminated against, ashamed of our own language. We couldn’t talk, I practically stopped speaking Paaikoka for almost a year. I also stopped wearing my tunic.

When I had interacted in my language in my community, it was a little difficult for me to pick up Paaikoka again. However, I never forgot it, after – I don’t know, about five minutes – it felt like my tongue was hard, but when I spoke, I spoke fluently.

“What we are trying to create here is an education that plants their roots, their feet on the ground, so that they are not ashamed of their culture, their different forms of learning, for example with Yoko, with Yagé, which are much more linked to spirituality and communication with nature.“

Q: Do you perhaps feel that this model of education that you received sought to eliminate your own culture?

A: Maybe not as an objective aimed at that, but it did influence in some way to reduce our self-esteem, to generate a kind of insecurity regarding our own clothing, our own culture.

I felt that there was no respect. In 1993 the topic of bilingual intercultural education appeared and I had to take on a pedagogical area of the topic, there the teachers talked about different cultures, so I questioned them: “I am from a different culture, but why am I supposed to be taught only Kichwa, I have to learn in my own language, my language also has its own linguistic structure” – I told the teacher – “instead of sending me to do the work in Kichwa, send me to do it in Paaikoka.”

Q: What do you consider were the negative and positive aspects of having received this traditional Hispanic education?

A: The negative thing is that they overshadowed us, they interrupted our own linguistic development and then they adapted us to their own way. The good thing is that I ended up learning something from other cultures to see how the world is different from mine. I began to want to understand what is happening in this diverse world.

However, I have always felt that there was a void. When I went to university I arrived empty, empty of my culture, my own knowledge and wisdom. And I have had to go back to studying, to practice these self-education processes. Now I think that the new generation will learn from its roots from the beginning and will contribute a lot to us.

Q: How would you describe the community-led education process that the Siekopai Nation is building?

A: What we are trying to do here is an education that sows their roots, their feet on the ground, that they are not ashamed of their culture, their different ways of learning, for example with Yoko, with Yagé that are much more closely linked with spirituality and communication with nature.

We do not want to ignore other cultures and other ways of conceiving the world like the Western one, we want to build bridges of understanding from this community-led education: recognizing in depth our own worldview, and from there, understanding what is foreign – that we understand, and are understood.

Q: Are you working on your own curriculum, and can you tell me about it?

A: When developing the curricular elements, it is important to ask: what are the most important areas for the Siekopai? Let’s talk about the topic of spirituality: what content should Siekopai spirituality have? Let’s talk about nature: how do we articulate ourselves, how do we understand each other, how do we interrelate with the river, with the water, with the trees? It’s important they no longer make us see a money tree, but a tree of life, a tree where the spirits are, where science is, where wisdom is.

Of course, reading and writing are necessary, but it has to be done from one’s own cultural practice. I am going to give an example: we Siekopai have about seven ways of weaving the sieve and each one is a model, each one of those ways. It is mathematics that our grandparents did, our own mathematics from our own conception. The mathematics that we can absorb from the Western world does help, but it must be transferred to our reality.

So the curricular elements have to be written as a life plan, like a great Siekopai Maloka (ceremonial house).

“Education and the territory go together, they go together because without the territory there is no education.”

Q: What does the Siekopai Nation need to implement this community-led education process?

A: We need to start designing and developing our teaching materials much closer to our reality, with cultural relevance. We also need to have our own educational autonomy, including administrative autonomy, so that it is not the Ministry of Education that makes decisions without the knowledge or without the participation of us as a nationality.

We also have to investigate living sources, making sure our grandparents participate, teaching us how to make a pot, how to make the sifter, the juicer, all of this focused on didactics, in this transmission of knowledge.

Q: How do you envision a young person who is educated with this new self-education, what do you think?

A: A child who develops in this educational proposal has to be a person who understands ethnobotany, they must understand what they have in their territory, what they have as their culture, this is the most important thing.

We would like them to be excellent biologists, excellent doctors, excellent communicators, excellent lawyers who can defend their people in the future, but for that, we want to form intellectual development in these issues.

Just like our grandparents, the best healers and experts of the jungle, the best biologists, we want to aim there. That they do not forget their culture, that they are authentic, that they are their own without needing to imitate, without needing to be other people, that they know how to think and act like Siekopai.

Q: How is community-led education linked to defending the territory?

A: Community-led education goes hand in hand with defending the territory. It originates from the territory. When we go along the river, we are doing education, when we are taking a rod to fish we are taking from the territory to educate for our subsistence, when we paddle and canoe we are also making use of that territory, therefore community-led education and the territory go together, they go together because without the territory there is no education.

Q: What messages do you give to people around the world who are going to read and listen to this, to these blogs and media products we’re making, what message would you give them?

A: We want to tell the world that we – native nations of the Amazon – exist and are fighting so that we can all continue existing as a generation of the human species. We contribute to that, so that all beings in the world can continue to coexist and defend, above all, our big house, which is this universe. That is why we invite you to participate in this great collective work where we all contribute toward generating less damage upon nature and upon the lives of human beings who want to live in a different way.