The Amazonian fires that captured the world’s attention in late August 2019 are a calamity of monumental proportions for our shared climate, biodiversity loss and health. While mass media attention has begun to shift its focus elsewhere, the fires have not abated and only risk worsening as the lower Amazon heads into mid-dry season. A study released September 11th by the Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Project (MAAP) demonstrated that over 40,000 ha of forest were both cleared in early 2019 and then burnt at the beginning of the Amazon’s dry season, as land owners claimed new land for agriculture and pasture using the slash-and-burn technique. This finding confirms that fires are happening on land that was previously forested, as opposed to being primarily part of an ongoing agricultural cycle, as some tried to claim.

This blog presents some of the science behind the disastrous consequences of these deliberate fires, which are but the most recent and palpable manifestations of the systematic and systemic pressures that the Amazon faces daily.

First, a point of clarification. From the Amazon basin to Africa and the Boreal region, there are forest fires raging across the globe in a prelude to our collective future. ALL of these fires are important and serious in their own right. However, some forests, for example the Boreal Forest, have adapted to repetitive cycles of fire. Indeed, the seed of the Lodgepole pine, which grows throughout most of the interior of British Columbia, Canada, is so thoroughly sealed with resin that it will only germinate when the high heat of one of the recurrent fires mollifies the pitch allowing it to open.

The Amazon forest has never been exposed to fire on a large scale. In its natural state, it is too humid to burn out of control. Thus, most Amazonian plants are what is referred to as “fire-naïve;” they cannot withstand the assault. While localized, controlled fires are traditionally used by certain indigenous groups in dryer regions for very specific purposes, such as clearing small plots, hunting tortoises or smoking out bees, the tragedy that we are all witness to now is a human-caused explosion in the number of large fires set primarily to make room for cattle. A combination of dryer conditions triggered by deforestation and climate change and its natural history leave the Amazon defenceless to this new, manufactured inferno.

Accelerating Biodiversity Loss

A view over the Amazon rainforest, Ecuador

The first victims of the fires – in what is an obvious statement – are the plants that are scorched and the animals that are driven from their home. In the Brazilian Amazon, there are on average 250 different species of tree per hectare. Imagine trying to play rugby – a rugby pitch is roughly one hectare – with 250 towering competitors each from a different team on the field. Living on and among the trees are multitudes of insects, frogs, fungi, mammals, birds and epiphytes. The number is not only unknown, but unimaginable. The individuals that are lost in the fires deserve their own unsung songs, but there is no salve for the biodiversity lost. Alas, some of these species live in just a few hectares of this uneven mosaic of a cathedral-forest. When their hectare-kingdom is gone, when their very body is defiled, and their entire biological cycle is destroyed, they are gone – forever. A recent UN-linked report by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) has highlighted that 1 million species are at risk of extinction across the planet and that the main driver in Latin America is habitat destruction of intact ecosystems by agricultural expansion, primarily for beef. Between 1980 and 2000, 42 million hectares of natural landscapes were lost to cattle production across the region.

The Yaku Glassfrog (Hyalinobatrachium yaku), a 2 cm see-through rainforest amphibian recently found by scientists and spotted here in ancestral Siona territory, Ecuadorian Amazon. Frogs breathe through their skin making them most sensitive to environmental changes

Threatening Our Shared Climate

Climate change as an issue has suffered from its “hereafter” and overly-technical image.

This changes now.

A confluence of recent events, beginning perhaps with the bravery of one girl – Greta Thunburg – and crowning with the highly symbolic nature of the recent, ongoing fires, has opened eyes to our shared climate future and saddened hearts across the globe.

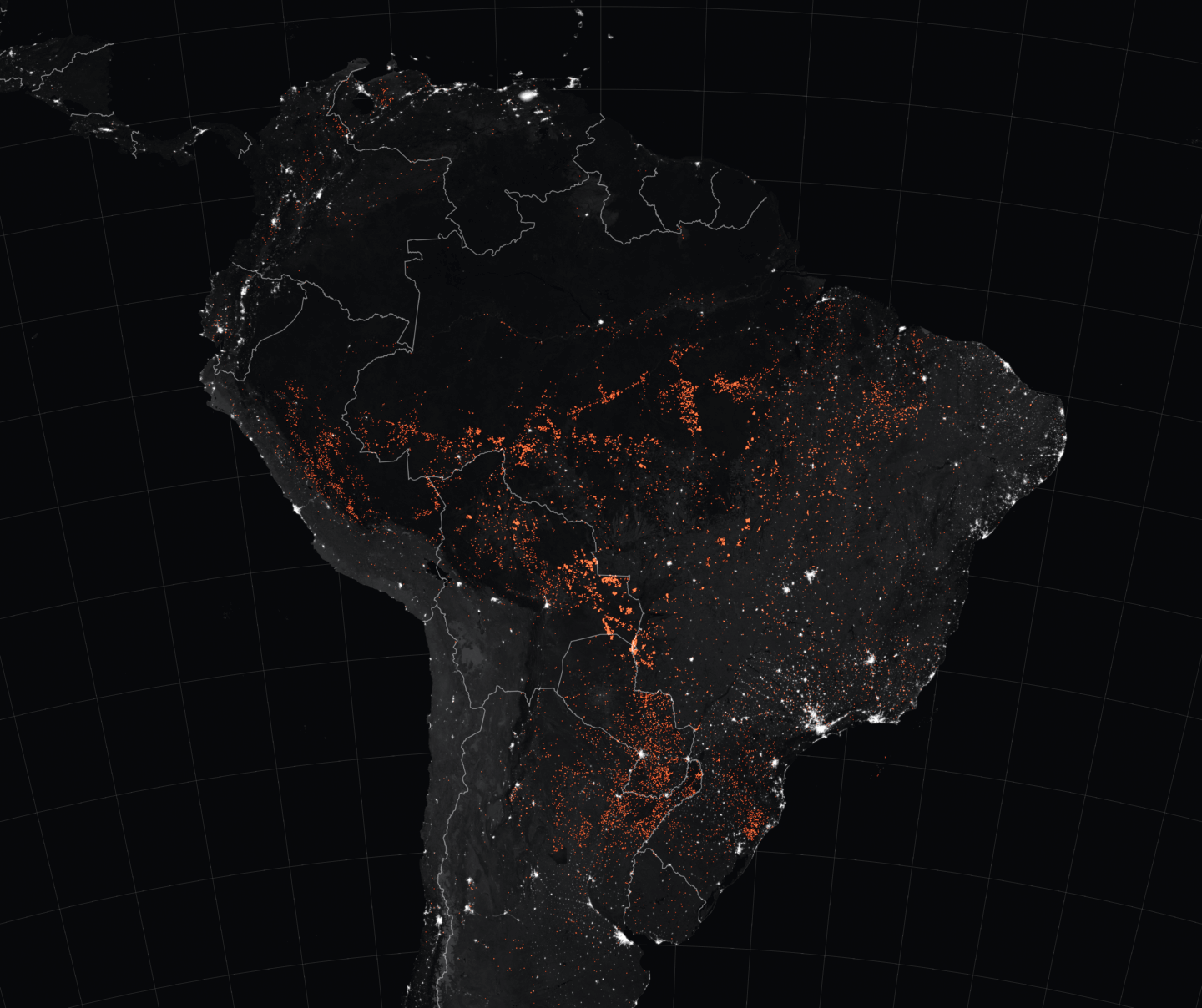

This map shows active fire detections in the Amazon rainforest in South America as observed by NASA’s Terra and Aqua MODIS between Aug. 15-22, 2019

The Amazon stores the vast majority of its carbon in the forest, as opposed to other ecosystems, such as the Boreal Forest, where much of the carbon is stored in the soils. While it will take time to know the true carbon cost of the 2019 Amazon fires, very preliminary estimates put the carbon released this year – only part way into the dry season – at 228 megatonnes (Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (Cams) via BBC). This is the equivalent of over 48 million passenger cars driven for a year.

A view of Indigenous Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau land in the Brazilian state of Rondônia being burned on Sept. 24, 2016. Photo: Gabriel Uchida

Yet, the perils are far greater than this initial carbon release. The Amazon acts as a huge carbon sink, which our planet desperately needs right now to absorb the carbon we continue to produce through our collective, voluntary blindness to the basic facts of climate science. The Amazon is currently still providing this invaluable service to us humans and the rest of the planet. However, prominent climate scientists Lovejoy and Nobre (2018) have implored us to open our eyes to the fact that a tipping point exists: a point at which the Amazon no longer acts as a carbon sink because the process that keeps it moist, and thus capable of capturing so much carbon, breaks down. This process of evapotranspiration – dubbed the Flying River – is essential to the functioning of the Amazon, but standing forest is also essential to its maintenance. It is the classic positive feedback loop, and when it breaks down the Amazon becomes a carbon source instead of a sink.

Deforestation in general breaks down the cycle of evapotranspiration by removing the trees that act as a biotic pump and “exhale” moisture to the atmosphere; but, forest fires have two impacts in addition to their role in tree removal. First, fires parch the remaining forests, which then create less rain (Lovejoy and Nobre, 2018) and become more vulnerable to future fires. Second, fires lead to “rain shadows.” Particles released into the air darken the sky making cloud formation more difficult and bind to water molecules in existing clouds, which are then less likely to release their moisture (Cochrane and Laurance, 2008).

Lovejoy and Nobre (2018) predict that the evapotranspiration system breaks down once 20-25% of the Amazon has been deforested. At this tipping point there simply are not enough trees to feed the Flying River. We are already dangerously close to this point. According to new research (Brazil INPE via The Washington Post), 80.7% percent of the original Brazilian Amazon remains, in other words, 19.3% has been cleared, leaving a buffer of 0.7 to 5.7%.

Endangering Health

The health of the entire world is impacted by the burning of the Amazon through the loss of climate regulation services as far as Northern California (Medvigy et al. 2013), to the disappearance of as-yet undiscovered medicines hidden in the Amazon Basin. But none are more impacted than the first peoples of the Amazon: the countless tribes that call the forest home and who are watching their memories, their stories, their futures go up in flames. This is unmeasurable.

An indigenous Waorani man hunting in ancestral Waorani territory, Ecuadorian Amazon

The tree stands, rivers and streams, and soils are forest people’s bulwark. Their entire traditional way of life depends on the integrity of these interrelated systems for food (plants, fish and game), building materials and crops. What might be carbon to some, or undiscovered medicines to others, are actual life support systems that have sustained thriving cultures for millennia. Amazonian soils are surprisingly poor for all that greenery. In fact, most of the nutrients in the system are in use at any given time, caught up in the verdant groves of tropical plants. Slash and burn not only unleashes copious amounts of carbon into the atmosphere, but it also casts off much of the nutrients that are usually cycling through the ecosystem (Compte et al. 2012), jeopardizing not only the natural forests’ ability to regenerate themselves, but also local people’s ability to cultivate crops.

Indigenous children in a Waorani community, Pastaza, Ecuadorian Amazon

Lastly, research has begun to document the direct harm caused to local people by pollutants released from fires (Machin et al. 2019). Fires and the drought that they cause have been linked to respiratory problems, especially among children. In periods of dry weather, hospitalizations for respiratory complaints soar throughout the Brazilian Amazon due to irritating particles billowing up from dry soil and forest fire fumes. (Smith et al. 2014). Furthermore, a very alarming observation was made by the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (Cams) and NASA’s Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) of a cloud of carbon monoxide – a highly toxic gas – leaving the borders of South America.

How to help

- The most important thing that you can do to help is to resist feelings of apathy and non-responsibility. The 2019 fires in the Amazon are NOT something that DOESN’T concern you. They concern us all – the carbon sequestration services that the Amazon provides regulate climate for all of us – and the list goes on. From this space of empathy and understanding of our interconnectedness, the other actions follow.

- Eat less beef. 80% of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon is human-caused clearing to make way for cattle. Most of this meat is consumed in Brazil, but 20% is exported and exports have grown 25% in recent years, much faster than the rise in domestic demand. Watch especially your beef consumption in processed and fast foods, which are more likely to contain meat from far away places, such as the Amazon.

- Share what you know and believe with those around you. Inspire people to care.

- Donate to the people who have demonstrated their commitment and ability to conserve rainforests through the ages – the indigenous peoples of the Amazon. By donating here, 100% of proceeds will go to local indigenous allies in Brazil, Bolivia, and Paraguay on the frontlines of these fires.

References

- Cochrane, M. A. and W. F. Laurance (2008). “Synergisms among Fire, Land Use, and Climate Change in the Amazon.” AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment 37(7): 522-527

- Comte, I., R. Davidson, M. Lucotte, C. J. R. de Carvalho, F. de Assis Oliveira, B. P. da Silva and G. X. Rousseau (2012). “Physicochemical properties of soils in the Brazilian Amazon following fire-free land preparation and slash-and-burn practices.” Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 156: 108-115

- Lovejoy, T. E. and C. Nobre (2018). “Amazon Tipping Point.” Science Advances 4(2)

- Machin, A. B., L. F. Nascimento, K. Mantovani and E. B. Machin (2019). “Effects of exposure to fine particulate matter in elderly hospitalizations due to respiratory diseases in the South of the Brazilian Amazon.” Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research 52

- Medvigy, D., R. L. Walko, M. J. Otte and R. Avissar (2013). “Simulated changes in Northwest U.S. Climate in response to Amazon deforestation.” Journal of Climate 26(22): 9115-9136

- Smith, L. T., L. E. O. C. Aragão, C. E. Sabel and T. Nakaya (2014). “Drought impacts on children’s respiratory health in the Brazilian Amazon.” Scientific Reports 4: 3726.