The Waorani lived as semi-nomadic hunter gatherers and defended one of the largest indigenous territories in Ecuador well into the 1960s, when American evangelical missionaries began to make inroads into the Waorani’s territory. The missionaries relocated the Waorani into permanent settlements, opening the territory up for oil exploration and extraction, changing the Waorani’s way of life forever.

Waorani hunters use traditional methods near Bameno

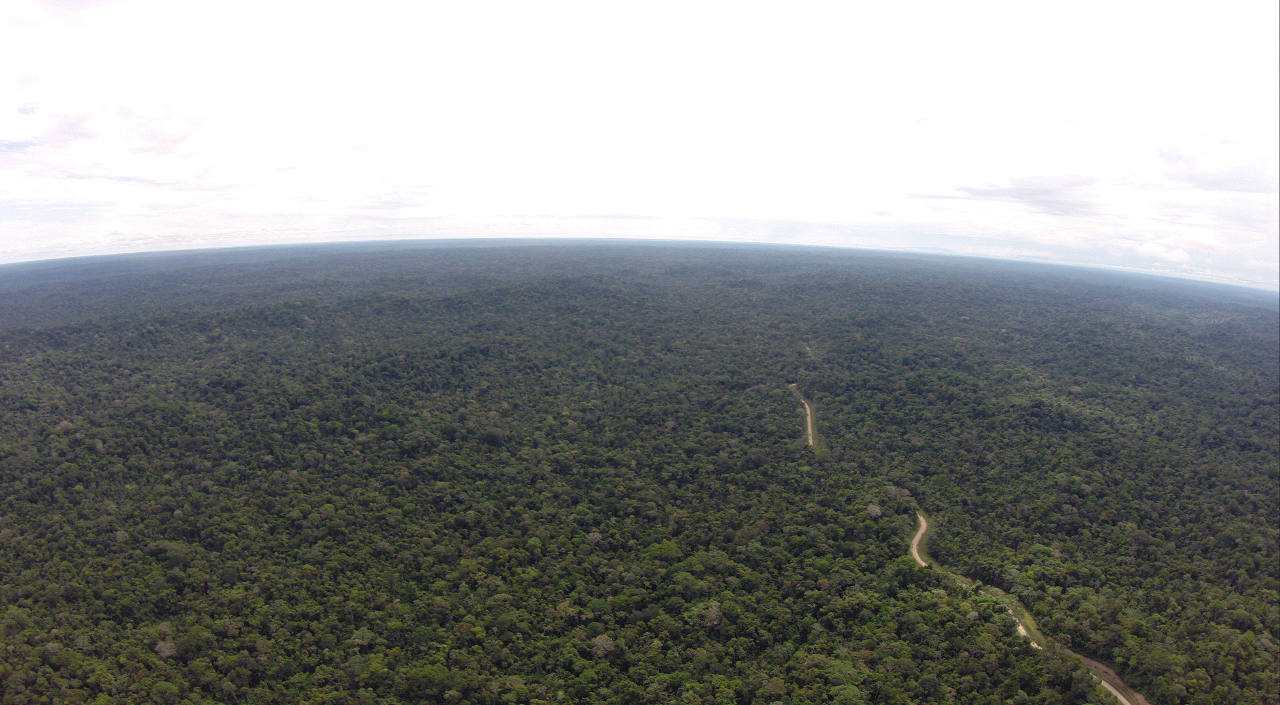

The Via Auca, named for the Kichwa word for Waorani, meaning “savage”, was the first and most extensive oil road to be built in the territory. From the Via Auca, smaller roads began to dissect the Waorani’s ancestral homeland, opening up more and more tracts of primary forest for drilling, deforestation, and colonist settlement. Today, dependency on the oil companies, violence and addiction plague many communities. Oil companies continue to encroach deeper into Waorani territory, including Yasuni National Park, considered by rainforest scientists to be among the most biodiverse places on Earth and home to the Tagaeri and Taromenani: Waorani clans who have resisted contact and whose territory grows smaller by the day.

Access to clean drinking water is precarious in many Waorani communities, especially those located along the oil roads. Along the Via Maxus oil road in Yasuni National Park, where streams have been contaminated by nearby oil operations, Waorani women clutching plastic jugs line up at dawn to receive their daily ration of water from the oil company, passed to them by a hose through a barb-wire fence.

The Via Maxus oil road in Yasuni National Park

The Waorani, whose cultural survival has reached a critical point, are also one of the most inspiring examples of hope in the history of the ClearWater water project. Young Waorani coordinators have led the installation of rainwater catchment systems in their communities, and to date 297 systems have been built, providing families with access to clean water in 22 communities.

Waorani coordinators, technicians and villagers working together to build rainwater catchment systemsk

Now the communities along the Via Maxus don’t have to rely on the oil company for their water. It may seem like a small thing, a metaphorical drop in the bucket when compared to the massive threats that face the Waorani’s traditional way of life, but this step is one of many that Waorani communities are taking with the support of the Ceibo Alliance. Waorani youth have been trained as mappers and are currently leading community mapping initiatives that will help their communities gain legal protections for their remaining pristine rainforest territories. Waorani women are working together to build alternative economies around the sale of their traditional jewelry. Waorani technicians, trained by the Ceibo Alliance, have already installed dozens of solar panels in communities so that families can access electricity without having to rely on the oil companies to provide them with gas powered generators.

These are just a few examples within the movement that the Waorani are building through the Ceibo Alliance, a movement that started with communities working and nationalities working together for clean water.