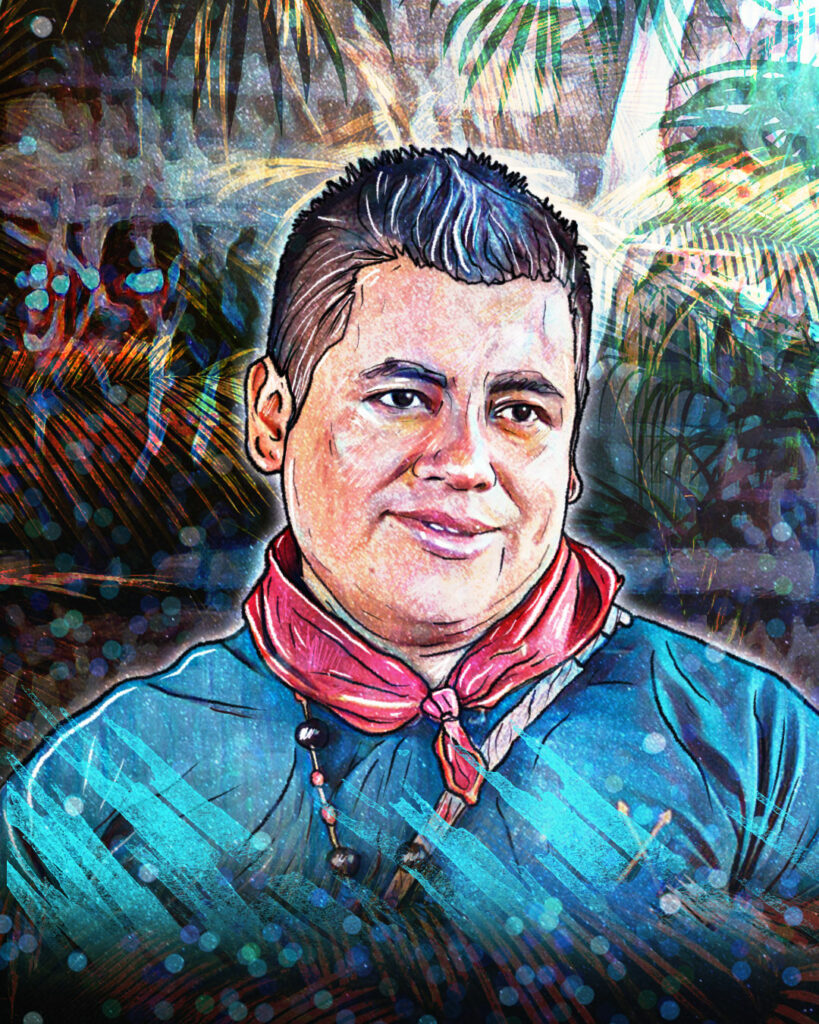

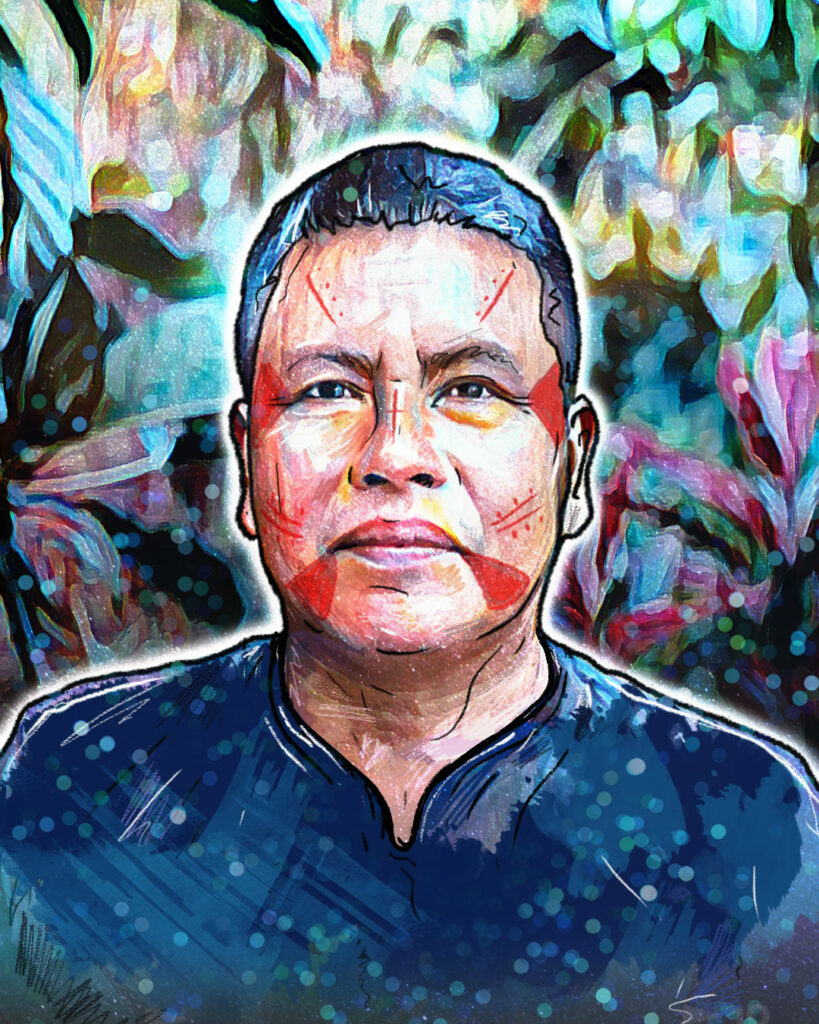

Despite the fear he had of the Cowori (non-Waorani people) as a child, Gaba Guiquita went to the little school in his Kenaweno community, where a Cowori teacher taught, with the little she had at hand, the classic school subjects in Spanish. Gaba and his classmates only spoke Wao Tededo, so they did not understand what their teacher was trying to teach, but they had to learn if they did not want to be punished with a ruler.

With a lot of effort from himself and his family, Gaba completed high school, and was later hired by the Ministry of Education as a teacher for the small school in his community, where he worked until 2013. His experience allowed him to learn about the difficulties and needs of education in the territory.

Gaba Guiquita is the current education leader of the Waorani Organization of Pastaza (OWAP) and from that position he works on the development of a proposal for community-led education. He dreams that this process will be a factor of social cohesion for the Waorani communities of Pastaza and that Waorani girls, boys and young people will reach the highest levels of education. In this interview, Gaba tells us what is being developed and why it is so important.

“The first path to community-led education is territory; without territory it cannot function”

Q: What was your experience as a teacher at your little school in Kenaweno?

A: I must tell the truth: a high school graduate does not have the training to work with students. I have felt it. I didn’t know how to plan, how to make the guides, I didn’t even know about the MOSEIB – Model of the Bilingual Intercultural Education System – which is the implementation instrument in the territories. I was only able to plan and work from what I remembered from the teacher who taught me in my childhood.

In my first year as a teacher, I received a total of five training sessions: two in the territory, another two in the city of Puyo and one more in Macas, Morona Santiago, managed by our own organization. Leaving the territory for the training was very difficult, you had to fly or go by canoe, and we had to fund it ourselves. The flight at that time cost about 200 dollars, and my salary was barely 150 dollars.

I learned a lot in the workshops. The most experienced teachers, some of whom have since passed away, taught us a lot. I was afraid of speaking in public and there I learned how to do it, I learned how to plan.

Q: How did the proposal for community-led education arise in the Waorani communities of the province of Pastaza?

A: Community-led education was born out of the territory in 2019 with 176 representatives or delegates and presidents of the communities and with the OWAP. This proposal comes right from the bases.

Q: What are the main teachings that Waorani community-led education proposes?

A: The first path of community-led education is the territory; without territory, it cannot function. There must be healthy forests, healthy waterfalls, the songs of the Pikenani [Waorani traditional leader], the ways of living of the Pikenani, ways of living of the young people, of the children. It must be in our language, that is very important; wherever they want a Waorani to be, they must speak their own language and in case a Waorani does not speak in their own language, then it means that they lose their own living culture.

One must learn from medicinal plants. If a Pikenani dies, we will not know what they know because Pikenani are like our teachers, like our scientists who have a lot of knowledge and vision; with them, it’s like receiving knowledge in natural sciences. So a student should go with the Pikenani to see a plant, then plant it in the school garden, name it in the Wao Tededo language, in Spanish, and also with its scientific name. The child must learn which plants are for fever, for diarrhea and they must also learn the Cowori ways. They are two worlds that we must continue to advance and build. And we are already working very well and advancing with the school gardens.

“If students do not know the territory, they cannot be defenders. Years ago when we were students at school, they gave us the map of the world, the continents and countries. The student and the teacher must first learn the map of the communities”.

Q: You are developing your own curriculum – what has that construction process been like?

A: We have been working to make our curriculum based on the MOSEIB – it is our bible . Making a curriculum is very difficult work, very hard. We have made several tours in each community such as Daipare, Kenaweno, Nemompare and now with Tepapare, Teweno and Gomataon to have for the first time a curriculum that is adapted to two languages, that is, Wao Tededo and Spanish. In that way, a student must share their experiences with the Cowori, and the Cowori must share their experiences with the Waorani.

There are many young people who in their Facebook posts have written: “Education is in vain.” This isn’t true! That is why we want this curriculum to become a reality and we want it to be approved by the Ministry of Education. We want to replicate it in each community so that teachers can work calmly with these guides, so that children, young people, and teachers know that we have a community-led education system which allows us to be autonomous and have self-determination.

Q: How has the application of the self-education proposal progressed? Is it approved by the Ministry of Education?

A: The Minister of Education and the Undersecretary were given information so that they could understand what is happening in the Amazon region, the lack of funds for teachers, training, and we also talked about community-led education. We haven’t gotten any updates since then. We are building the framework so that once it is ready, we can present it and have it approved.

Meanwhile, we have carried out workshops in several communities. Now we have our own Wao volunteer teams, we have the Daipare process where there is a Montessori classroom where children learn, do dynamics, sing, laugh, and always walk. There is a Pikenani who also teaches the Cowori professor, and Cowori also shares with us. We have materials from their own environments and also from the Western world, so they work with both parts.

For the weekend, a Pikenani always plans to work with crafts to teach how to weave chambira, how to make a spear, how to paint colors, how to dance and tell stories, legends, myths. We want all of this so that the Waorani culture does not end!

We have evaluated among the government councils, the community, students and teams of young pedagogues who support us, and we have seen that we are truly strengthening the best path forward.

I have always said that OWAP is willing to dream. Today we have about six Waorani university students. I always tell them, you are going to study, get your certificates and then you must return to lead the organization and be the best example for other communities. If we unite all the communities we will be perfect, and over time for future generations, perhaps even have a university within the territory.

Q: What are the main challenges you have as an organization to implement community-led education in the communities?

A: First the approval, that is my first important point, that the curriculum is approved and then I want to hold an assembly for all Pikenani together with the teachers and the children to have a great celebration. With that approval we can begin to replicate in the communities, advise the teachers and the community so that we are all on the same path.

The teachers must always be with the Family and Parents Committee, the families must watch over the teachers as well as the president of the community, they must all be in unity. We can always improve in unity. If we are separated, community-led education does not work.

Q: How is this process of community-led education linked to the defense of the territory?

A: If students do not know the territory, they cannot be defenders. Years ago when we were students at school, they gave us the map of the world, the continents and countries. The student and the teacher must first learn the map of the communities.

We are all working in unity: leaders of territories, of sovereignty and of education, in order to prepare these proposals. The territory leader knows very well how many Waorani communities of Pastaza exist, how many inhabitants and how many teachers, where there are areas in danger of mining, where there are hunting areas, so we are working on all of this on the maps to be able to replicate it to other communities so that the Cowori students or teachers can also learn.

We must continue fighting. If we do not fight and defend our territory, others will come to end it. The Pikenani are right, we should not just obey the miners or the oil workers because we have defeated the Ecuadorian State; we must continue working in unity.

As a leader, I am very proud to walk among these various communities, to know and share the processes with our brothers from neighboring countries like Colombia. Many pedagogues, we have listened to each other, we share this struggle with the Cofán brothers, Siekopai and Siona. If I ever stop being a leader, I hope, God willing, I can continue being an advisor because I want to continue promoting community-led education.