This story was originally published in El Pais.

___

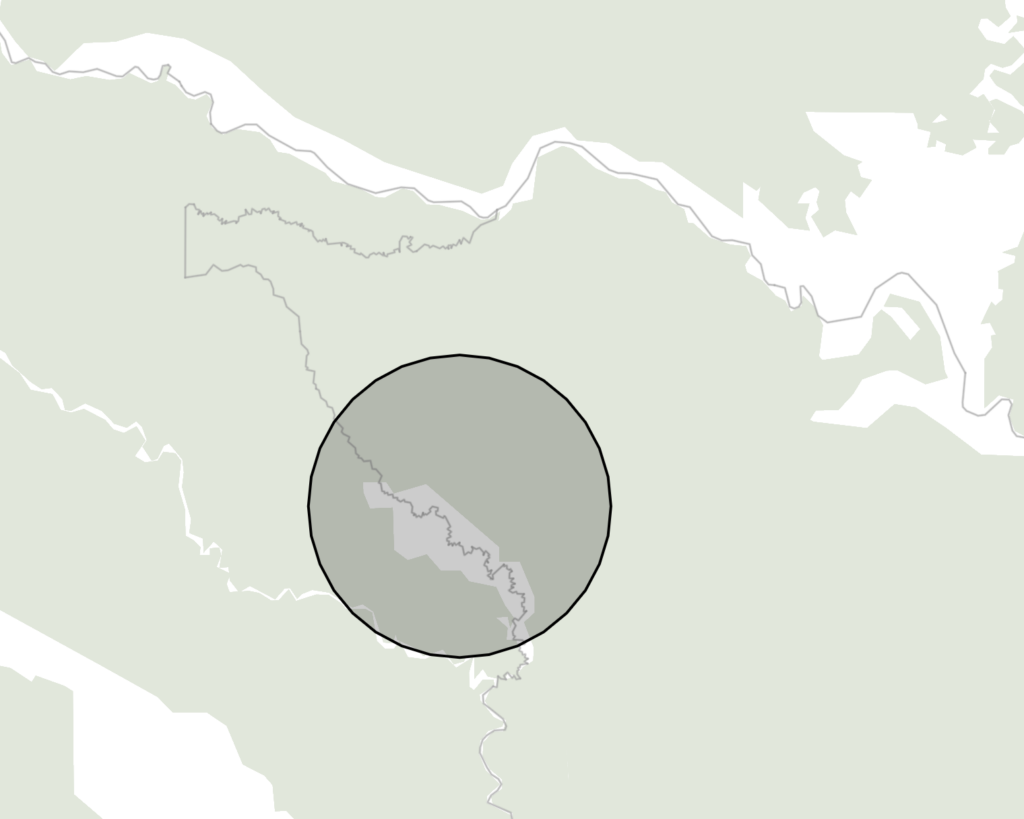

The Siekopai people will finally be able to return to their ancestral home, to Pë’këya, a territory within Ecuador, along the border with Peru. The area is where this Amazonian tribe lived for centuries, until they were expelled in 1941, due to the war between the two countries. According to a ruling issued on Friday, November 24, the Ecuadorian government has guaranteed them ownership of a piece of the jungle: a total of 42,360 hectares, also known as Lagartococha. The judicial decision (the second one related to this case) is “historic,” explains Justino Pianguaje, the head of the Siekopai Nation, who spoke with EL PAÍS by phone. For the first time, Ecuador has recognized an Indigenous population’s right to “possess a territory that has been declared a protected area.” Pianguaje points out that this ruling can serve as a precedent for other Indigenous communities that are trying to regain control of their land.

The 2008 Constitution of Ecuador recognizes the right of “Indigenous communes, communities, peoples and nationalities to maintain possession of ancestral lands and territories and obtain their free allocation.” But there was an exception: the spaces included in the National System of Protected Areas, for which the regulations contemplated transfer (essentially, the ability to reside on the lands), but not full ownership. In 2017, the approval of the Organic Law of Rural Lands and Ancestral Territories opened the door for protected spaces to also return to the hands of their original owners — something that has just happened with the return of Pë’këya to the Siekopai. The community has about 720 people in Ecuador. There are more than 1,000 in total, with members of the tribe living in Peru.

The court has also obliged the Ministry of Environment, Water and Ecological Transition of Ecuador to apologize publicly to the Siekopai, in a ceremony set to be organized within its territory. The judges ruled that the ministry “failed to fulfill its obligations to guarantee the rights of the Siekopai Nation.”

“This piece of land is what will allow us to continue existing as an ancient people.”Justino Pianguaje, head of the Siekopai Nation

According to Piaguaje, the recovery of Lagartococha was the “key” to preventing the disappearance of a community that has been struggling to return home for more than 80 years… a community that was doomed to “disappear.” “This piece of land is what will allow us to continue existing as an ancient people, as a people who have shown that we are Amazonian, with a different culture, a different wisdom and a different language,” explains the head of the Siekopai.

The connection of this town with its land and its past is intrinsic to its essence and its reason for existing. “Many believe that we want to return for the sake of beauty, but that’s not the case. My grandfather was there, drinking yagé (ayahuasca); my grandparents’ home was there. That’s why we continue to feel [a connection] and want to return. It’s not a problem of land — it’s a matter of the spirit, of not suffering anymore,” argued Maruja Payaguage, before the three judges of the Provincial Court of Justice of Sucumbíos, who ruled on granting ownership of Lagartococha to the Siekopai.

Piaguaje was able to share the ruling in an assembly with his people this past Monday. The text recognizes the suffering that Payaguage mentioned, which was particularly experienced by the Siekopai elders, due to not being allowed to return safely to their territory. “Cesario Piaguage Payaguage — at 112-years-old — wished he could die there, to be able to fulfill his ritual cycle. Like him, many other grandparents died without being able to be at peace spiritually,” the document states. “Cesario died on April 5 without seeing his dream come true,” Piaguaje laments.

Upon restoring the land to the Siekopai, the Ecuadorian court also mentioned the testimony of “children, adolescents and women. [They demonstrated] how knowledge about the name, location and use of plants, fishing or hunting practices, goldsmithing — and even ritual practices related to the transition to adulthood, gestation, or upbringing — and the explanation of their origin as a nation are only possible to know and experience in the Pë’këya zone.”

Pë’këya, the ancestral territory of the Siekopai

Also known as Lagartococha

A long battle

Of the 100,000 hectares that originally made up Lagartococha — where other Indigenous groups now live — the Siekopai have recovered just over 40%, a total of 42,360 hectares. “Fortunately, they contain the largest number of sacred places for us, where our link with the lagoons and the spirits of the jungle is,” Piaguaje explains. Among those places, the head of the Siekopai Nation mentions Ñañokomasira, where the ancient wise men of his community “reached an agreement with the mythological beings of water” to settle a war. There’s also the sacred river Emuña, as well as Kwiñajaira, “a historical site where our grandparents found medicinal plants to defend themselves against diseases,” Piaguaje notes. It’s precisely in this location where the ancestors of the Siekopai made kwarawëko (“syrup” in the Paikoka language). Their descendants used this during the Covid-19 pandemic. Piaguaje claims that it worked much better than “modern medicine.”

This fight — according to Piaguaje — was started by his grandfather, Cecilio Piaguaje, when the Ecuadorian-Peruvian War ended in 1942. “After the conflict — which separated Siekopai families between Ecuador and Peru — he wanted to return to his territory. He began to look for a way to reunify his people, but he never succeeded due to harassment.”

The sentence itself recognizes this persecution. “This Amazonian people had to leave Pë’këya for reasons beyond their control resulting from the war between Ecuador and Peru in 1941 [and also because of] other conditions of dispossession. They have attempted to permanently return since then, despite the threats, harassment and obstacles that have existed, derived from the militarization of the border and the subsequent creation of the Cuyabeno Wildlife Reserve.”

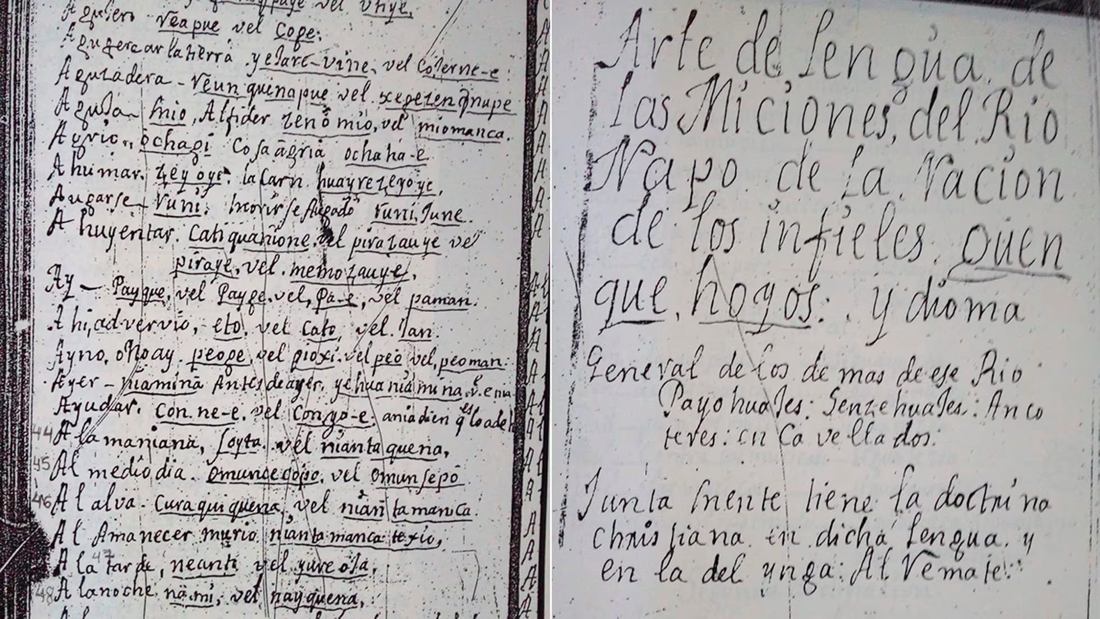

To recover the land, it was necessary to demonstrate that they were the original inhabitants. Coming from a culture that has an oral tradition, this meant that they had few materials to support their claim. However, several Jesuit documents — including an anonymous manuscript from 1753 — demonstrated that the Siekopai had been living in Lagartococha for centuries. The text — preserved by the New York Public Library — contains about 1,200 words in Paikoka. “The oral tradition of the Siekopai is very precise, but in this document, [the translation from Spanish to Paikoka is strong],” affirmed Argentine researcher and anthropologist María Susana Cipolletti, during a phone interview with EL PAÍS this past May. She participated in the judicial process as a witness.

For “the right to restitution to exist,” it’s essential that “the Indigenous people maintain contact or a relationship with these ancestral territories in one way or another,” according to the Ecuadorian judges. The ruling states that this condition has been proven: “It has been demonstrated that the Siekopai Nation is the ancestral owner of the territory of Pë’këya, with which it has maintained a historical, spiritual, cultural and material relationship that has been essential in the creation and development of their cultural identity and worldview and that is essential for their physical and cultural survival.”

“I finally feel an internal peace, for having demanded respect for the rights of the Siekopai and having guaranteed this territorial space for current and future generations,” Piaguaje celebrates. He is convinced that this result will allow his people to “avoid extinction.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition