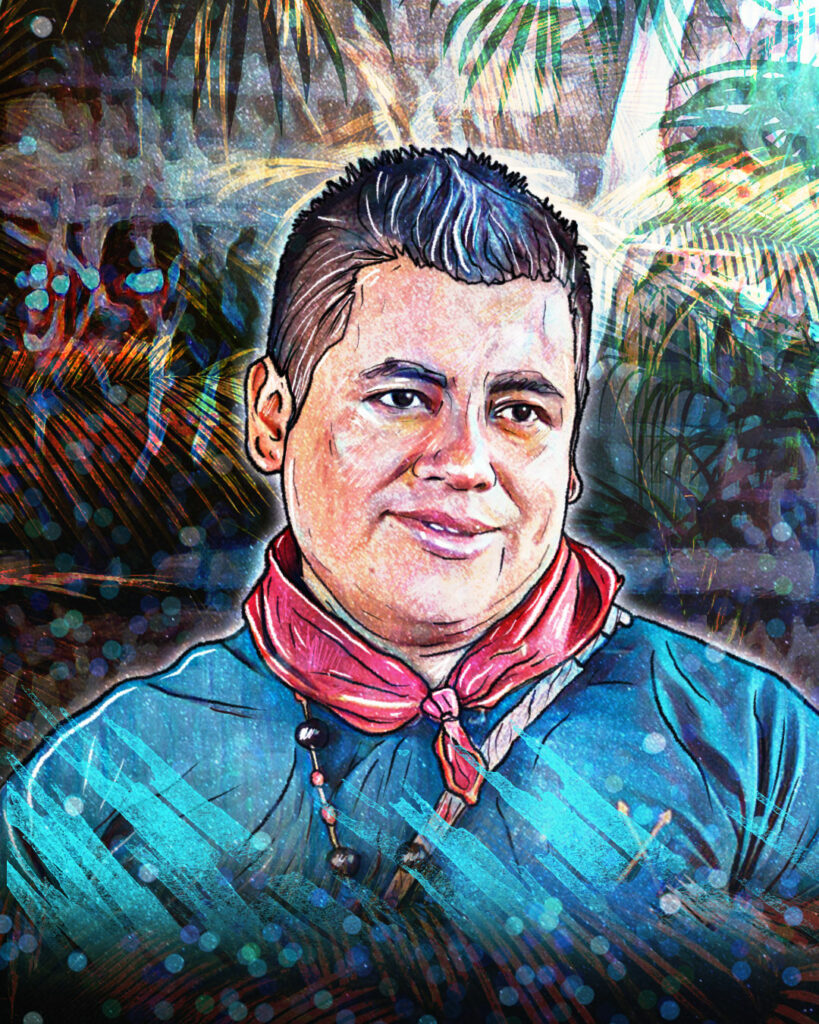

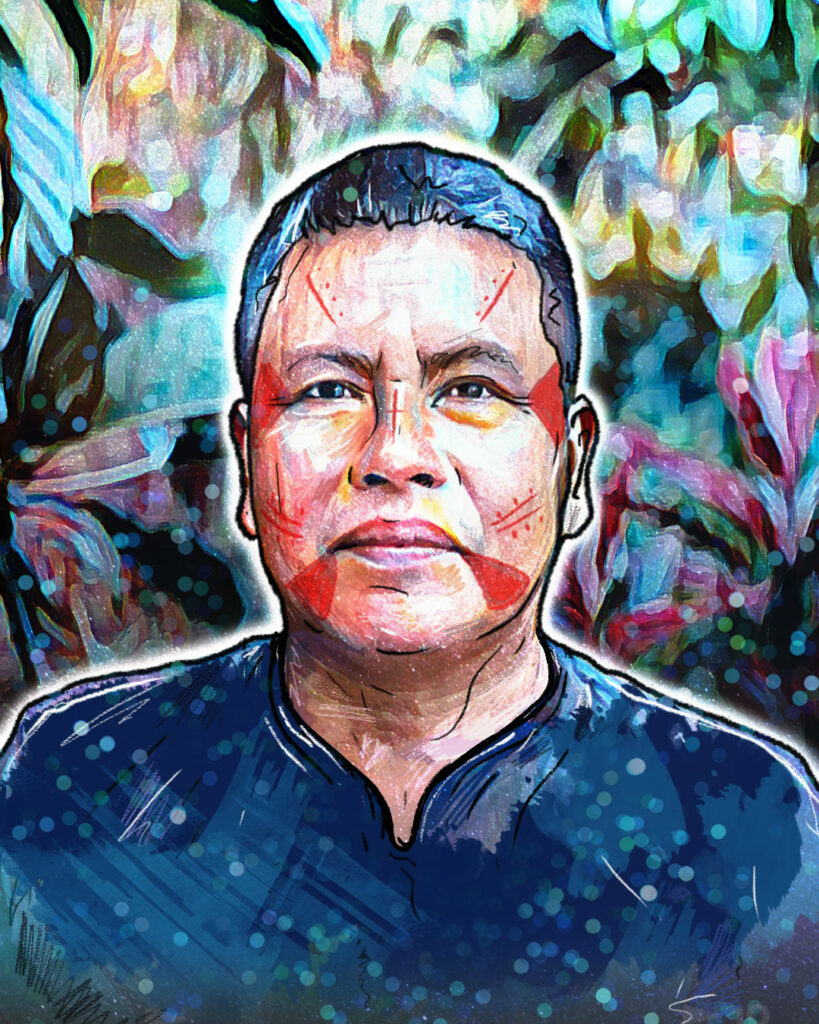

Waorani leader Nemonte Nenquimo travels the world spreading the word on how essential it is that Indigenous knowledge be incorporated into strategies for mitigating climate change, due to the intimate relationship of Indigenous peoples with their territories and the ancestral wisdom that has allowed them to take care of the largest areas of forests in the world. But what would you think if we told you that community-led education is one of these strategies?

In this interview, Nemonte tells us about the dream and the fight for Waorani boys and girls to learn in freedom, in the forest, recognizing the territory to be able to defend it, and at the same time having the tools to communicate with the outside world, without this exterminating their culture. She tells us why the educational system must change.

Q: What was it like for you to go to school?

A: It was very difficult. We had to get up early, comb our hair, put on our uniform, get in formation, sing the national anthem, go into the school and then the teachers very quickly explained the letters and mathematics and literature and drawing. If we didn’t understand, the teacher would punish us with a rope or send us outside. They were teachers who came from Puyo and Ambato [cities 75 and 138 km away, respectively]. They spoke Spanish, and when I was six years old, I didn’t understand the Spanish language that well. Speaking, writing, and reading were very difficult for me.

Q: How did the education you received influence your life?

It was a positive thing to learn to read and speak the Spanish language. That was a very important tool to be able to communicate to the world. But what I saw in my childhood wasn’t enough for me. Why couldn’t they also teach me in Wao Tededo, why only in Spanish? For me it was a little confusing. I grew up thinking that I was obliged to learn within that education system and it was very difficult for me because I wanted to be free, learn outside, singing, laughing, and feeling free. Otherwise, I felt oppressed having everyone sitting in the classrooms, locked up, memorizing, shouting the letters. That kind of learning made me uncomfortable.

It is very important to have education from outside, but it is also very important to have our own education, our territory, our language, our songs, our knowledge through the forest, the environment, all the interculturality for our autonomy.

“The Ecuadorian State system is not designed for the territorial cultural context. Children have to learn from their own context, not by being in the classroom memorizing, learning theory, but by doing practical work in their environments.”

Q: Do you feel like perhaps the education system was trying to eliminate your culture? What do you think education should be like?

A: I think so. The thing is that the Ecuadorian State system is not designed for the territorial cultural context, I have seen that since my childhood, but it is a system that is very strong.

Children have to learn from their own context, not by being in the classroom memorizing, learning theory, but by doing practical work in their environments: by going for a walk, for example, in natural sciences they can be explaining where there is water, where there is the forest, by walking, doing activities with the children. In mathematics they can count the branches, the stones, the seeds; these are material objects from the environment, hence there is another way of counting, other ways like our grandparents did. The Law on Bilingual Intercultural Education already speaks of the right to be taught in the environment, according to our worldview, but that is not fulfilled.

Q: How do you see the education that Waorani children and young people are receiving now, and what made them decide to begin this immediate process of community-led education?

A: There have been difficulties because the Waorani teachers have been trained in the system of the Ministry of Education, which does not have our cultural context, but rather that of the culture of the Ecuadorian Sierra, which is only translated for other nationalities, and they have already gotten used to working that way.

That is why when I was president, the first female president of the Waorani organization of Pastaza (“OWAP”), the need to work on education issues for our communities emerged. So we made a diagnosis with the teachers, with the students, with the mothers, then we held a consultation assembly with the communities that have schools in Pastaza. There the parents saw that it was necessary. They said, we want our own education! Our children should not lose the connection with our grandparents, that appreciation and value they should have for the jungle. Then we started working on our own curriculum.

We are building that to improve, so that children can feel good, and free, so that their parents and young people can feel part of it. That education is the way out, and with which they will not lose their territory, their language, their environment. They will be teachers or leaders who link their territory and their culture. I am happy because we are already on that path.

“We are going to continue demanding our right for our girls and boys, that they feel their own education and that they feel free and happy“

Q: Why is it so important that the curriculum you are now designing be approved by the Ministry of Education?

A: The law already speaks about the right for all nationalities to build their curriculum, so the Ministry must respect that, that is what we are asking for. If they do not respect this, it means that the Ministry of Education is violating our rights, those of boys and girls, communities and Indigenous nations.

The Ministry has to listen to the needs of each of the nations. The government platform cannot be the most important, that for me is like colonization. As the evangelicals did by bringing and saying – Jesus is salvation, your beliefs are bad, dark – they disconnected our beliefs. The same is going to happen with the issue of education. The State system is important, we have to comply; but at the same time, there is the right of Indigenous peoples to build their own autonomy, their own worldview.

We are going to continue fighting until they approve our education, we are not going to wait for the ministries to tell us what to do, we are not going to allow that. We as peoples and communities are going to continue demanding our rights for our girls and boys, that they feel their own education and that they feel free and happy. Until then, we will continue demanding.

Q: How is this proposal of community-led education related to the defense of the territory?

A: I think that it is very clearly and strongly related. It is very important for children to know why their grandparents defend the territory, why the forest is important, why water is important, what the plants are, who you should go to when you get sick, what you should do. So you help connect the children, help them value their culture that sustains the transmission of knowledge that can generate their children in the future. Otherwise they will disconnect from their realities, from their own complex contexts that exist within the territory. They will only depend on memorizing another culture.

Community-led education is a tool we can use to take decisions about what happens in our territory, otherwise we weaken, we disconnect from our roots, from our culture and we will only be singing the national anthem instead of singing our culture: “ eeee eeee…….” [“our grandparents defend this territory, thanks to our grandfather we still have a forest that gives us food and water”].

The Ecuadorian State does not understand what education represents, it believes that the lack of education is resolved by making a cement school. It assumes we are going to memorize and that’s it, it thinks that this is quality education. No, I believe that the government’s education system has to change, they have to respect the rights of Indigenous peoples.

Q: How do you imagine community-led education? What will a boy or girl who is educated in this new model be like?

A: I believe that the child should be speaking and teaching their knowledge in their language to other boys and girls who are also learning. Our dream is that they are the men and women who are teaching in their territory giving their knowledge, their value, their culture, their identity. Our dream is that they speak their language, sing their language, who has an understanding and a knowledge that helps to defend their territory, their environment, their culture and to value its context and its beliefs, not simply accepting what is from the outside system and extinguishing their own culture.

Q: What messages do you want to give regarding community-led education?

A: I give the message that community-led education, for each of the nationalities, is the only form of resistance in order to be in contact with our nature, with our culture, with our ancient knowledge. Otherwise, if we do not have that education, that system will exterminate our culture and our territory. That is more important; to have our own education is to continue living and be free and happy in our territory.