Facing the fiery scenario in South America, we have seen the need to express ourselves publicly and denounce the dramatic situation in which these affected groups live. We are Indigenous Organizations, Allied Organizations and specialists working to protect PIACI (Peoples Living in Isolation or with Initial Contact) living in the Amazon and the Great Chaco.

PIACI are under constant threat. Current fires aggravate their situation and put at risk their physical integrity. A predatory development model, along with the negligence of the state to protect these peoples have resulted in an increase of their socio-epidemiological vulnerability.

Peoples Living in Isolation have a condition of vulnerability in the context that drives Western society. Among the conditions that have created this situation, we highlight the constitutional dimension, related to the development policies implemented in the region that are associated with autonomous and / or illegal initiatives. They constitute vectors that increase the life threatening situations of these populations. For this reason, governments don’t feel the need to give special attention to PIACI.

We publicly defend the PIACI and demand that the governments of Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru and Venezuela take immediate measures to counteract such fires and, in coordination, implement special protection measures for these peoples, respecting their self-determination and decision to continue living in isolation.

We are aware that behind the burning of the Amazon, the Chiquitanía and the Great Chaco there is a million dollar market In Brazil, “setting fire to an area of 1,000 hectares costs around 1 million reais in the black market.” Who pays and what do they earn?

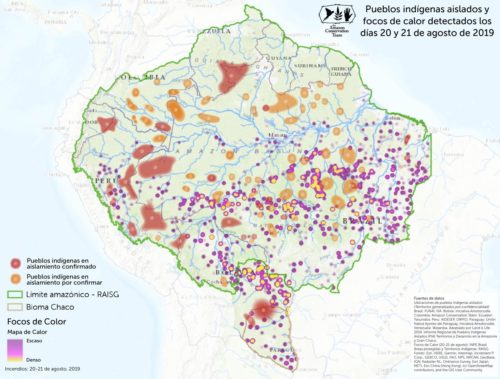

We, the Indigenous Organizations, the Allies and the experts of PIACI present in collaboration an overview of the seven countries of the Amazon Basin and the Great Chaco in Paraguay. We have identified 185 records of isolated indigenous peoples in the region, from those, the existence of 66 has been confirmed.

Bolivia

So far in 2019, 1 million hectaresi of forest have officially burned. From the end of July to August, the forest fire of the Chiquitaníaii devastated 780 thousand hectares. The most affected territories comprise the region of Chiquitanía and the Ayoreo, Chiquitano and Monkoxi Territories. Dry forests have also been severely affected and have disappeared along the border with Paraguay. This area had been decreed with intangibility for Ayoreo Isolation Peoples and the Guaraní Territory. These areas represent the last refuges for the survival of PIACI and are increasingly threatened by agribusiness and the government.

Brasil

The Brazilian Government’s answers to these problems have been completely disrespectful to the constitutional principles. For months, the president of the government, Jair Bolsonaro, has delivered speeches against indigenous peoples and the environmental movement. He has disrespected environmental legislation. The government is subject to international repercussions in the face of Brazilian scandals and the pressure of the G7.

Given this, a crisis cabinet was instituted and thereafter initiatives were taken; discussion and contempt were the only two pronouncements of the president and his team to the international community and especially before the civil society organized in favor of Brazil.

Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon since July (or prior), is 278% greater than during the same period of 2018. These are official numbers of the INPE. Between August 15 and August 20 of this year, 131 Indigenous lands have burned in Brazil. These numbers keep increasing because every day there are new fires. These data have been collected by Ananda Santa Rosa and Fabrício Amorim based on the Fire Information System.

The most dramatic situation is that of two groups of indigenous peoples in isolation. In Brazil there are 114 records of communities of Peoples Living in Isolation, of which 28 are confirmed by the official indigenist government agency or FUNAI. How many fled the fire? The information collected suggests that 15 fires were counted in lands where there are records of Isolated Indigenous Peoples, especially in the states of Mato Grosso, Pará, Tocantins and Rondônia. FUNAI still doesn’t have reliable data to determine how many were affected.

Colombia

In most countries, fires are a result of the interests of the development model implemented. The Institute of Hydrology, Meteorology and Environmental Studies of Colombia – IDEAM, registered 138,176 hectares deforested in the Amazon in 2018iii. Although the fire season in Colombia is usually between January and February, the accelerated deforestation affects the corridor between the Andes mountain range -Amazon – Orinoquía. From 2016 to 2018 the Colombian Amazon has lost 478,000 hectares of forest of which 73% (348,000) corresponds to primary forest, and, so far in 2019, alerts indicate the additional loss of 60,600 hectares, of which 75% (45,700 hectares) was primary forest. These mainly impact four protected areas: Tinigua National Parks, Sierra de la Macarena, Nukak National Reserve and Chiribiquete mountain range.

The Serranía de Chiribiquete National Park, home of at least two isolated villages still pending confirmation, the Carijona and Muruiiv peoples, lost 2,600 hectares since their expansion in July 2018, of which 96% corresponds to primary forestv.

On the other hand, despite not being directly affected by the fires, the Río Puré National Natural Park, which houses the thick tropical rainforest, and pending confirmation of the peoples of the Yuri – Passévi, is under pressure from exploitation and hydrocarbon explorationvii, the advance of the agricultural frontierviii, the development of road infrastructureix and miningx.

Ecuador

In Ecuador there have been no large fires in the Southern Amazon. However, mining activities are mainly conducted on indigenous territories in the South Amazon of Ecuador, causing a huge loss of biodiversity, water pollution and the displacement of Shuar indigenous communities.

It has been observed through satellite images that in recent years there has been an increase in rainfall and the creation of flood zones in the northern Amazon. In the past decades, these have been destroyed and contaminated by oil activities. The advance of the agricultural border and the local government-driven development strategies encourages deforestation in this area. The opening of new roads encourages colonization and displacement of Waorani and Kichwa indigenous communities.

The Yasuni National Park has not been affected by fire, but the exploitation of oil by new roads and platforms puts at risk the survival of the indigenous groups living in isolation, such as the Tagaeiri and Taromenane.

Paraguay

In Paraguay, the agribusiness production model is primarily responsible for the large fires that consume the natural forests of the Great Chaco. The use of a fire management system that was applied to natural environments in the past, which was limited then and with less destructive impact, today poses one of the greatest threats to life.

One million hectares of forests have disappeared in the past week, all vital areas for the isolated Ayoreo people in the Great Chaco region, the second largest forest in South America after the Amazon.

Nature reserves represent the few remaining shelters for isolated Ayoreo groups, as farms “devour” all forests based on capital production from livestock and exploitation of natural resources.

The absence of the Paraguayan state in the control of nature reserves and in the protection of the nature and life of people living in isolated regions is proof of its lack of interest in the conservation and protection of the country’s heritage, as well as the lives of people who choose a sovereign and sustainable lifestyle with nature, in its most literal and profound sense.

Perú

Most forest fires have occurred in mountainous areas (Cusco and Ayacucho), however reported jungle fires, though currently few, are directly linked to the PIACI territories. These are having a serious impact on the conditions of the territory and on the quality of air and natural resources. These fires are affecting the rights to life, health, and food security of the people that inhabit these lands.

One of the detected fires is located in the proposed area for the creation of the Western Divisor Mountain Indian Reservation (Ucayalí, Loreto), which already has the official recognition of the isolated peoples who live there and overlaps the Serra do Divisor National Park, also connecting with the Isconahua Indigenous Reserve. The second fire is in the Iñapari district (Tahuamanu, Madre de Dios) near the Alto Purús National Park and the Mashco Piro and Madre de Dios territorial reserves, being part of a larger PIACI displacement area known by indigenous organizations such as: Corridor border area Pano-Arawak (Peru, Brazil).

Although these fires are already under control – according to official information provided by the Madre de Dios and Loretoxi Regional Emergency Operations Center – the concern is compounded by the fragile territorial protection of these reserves and the lack of prevention for such emergencies. In Peru one of the main territorial threats is the increase of deforestation and illegal activities within them.

It is important to note that the PIACI territories in Peru are located mainly in areas of international borders – especially along the border with Brazil, where the proliferation of fire sources has been registered. For this reason, there is a chance that the fires will move towards the west in certain sectors, posing a serious risk to PIACI and their territories in Peru.

Venezuela

In Venezuela there are groups of three indigenous peoples in voluntary isolation or initial contact (Hoti,Uwottuja and Yanomami) in the Amazon region, specifically in the Amazon and Bolivar states. The Venezuelan Amazon region covers a total of 453,950 km2 in what is also called Guiana, which is inhabited by more than 25 different indigenous peoples.

There are currently no reports of fires affecting areas where peoples living in isolation are located. However in both the Amazon and Bolivar states, the government entities developed illegal mining activities involving different actors. These include irregular armed groups that guard the mining camps and in many cases they threaten the members of the indigenous organizations that denounce the problems. The Amazon state has a total of approximately 6,000 miners exercising gold and coltan mining.

This situation particularly affects groups in isolation or initial contact, since these illegal activities take place in areas near their habitats, impacting their possibilities of physical and cultural subsistence. Currently the Wataniba Association together with the Regional Organization of Indigenous Peoples of the Amazon (ORPIA) make efforts to make the situation visible and make the State of Venezuela assume protection policies towards these isolated groups and their territories.

Signed by

- Asociación Interétnica de Desarrollo de la Selva Peruana – AIDESEP (Peru).

- Central de Comunidades Indígenas Tacana II – Rio Madre de Dios – CITRMD (Bolivia).

- Coordinadora de las Organizaciones Indígenas de la Cuenca Amazónica – COICA (Regional).

- Coordenação das Organizações Indígenas da Amazônia Brasileira – COIAB (Brasil).

- Confederación de Nacionalidades Indígenas del Ecuador – CONAIE (Ecuador).

- Confederação das Nacionalidades Indígenas da Amazônia Equatoriana – CONFENIAE (Ecuador).

- Conservation Team Colombia – ACT (Colombia).

- Fondo Ecuatoriano Populorum Progressio – FEPP (Ecuador).

- Federación Nativa del Rio Madre de Dios y Afluentes – FENAMAD (Peru).

- Grupo de Trabajo Sociambiental de la Amazonía – WATANIBA (Venezuela).

- Iniciativa Amotocodie – IA (Paraguay).

- Land is Life.

- Organización Payipie Ichadie Totobiegosode – OPIT (Peru).

- Organización Regional de Pueblos Indígenas del Oriente – ORPIO (Peru).

- Organización Regional de Pueblos Indígenas de Amazonas (ORPIA) (Venezuela).

- Organización Nacional de los Pueblos Indígenas de la Amazonía Colombiana -OPIAC (Colômbia).

- Pueblo Kichwa de Sarayaku (Ecuador).

Notes

- i https://www.hoybolivia.com/Noticia.php?

- IdNoticia=300903&tit=un_millon_de_hectareas_quemadas_ruben_costas_dice_que_es_imperioso_aceptar_la_ayuda_internacional

- ii Reporte especial de Fundación TIERRA al 22 de agosto de 2019, sobre el incendio de Chiquitania. En: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eGP-YSW3fss

- iii IDEAM. http://www.ideam.gov.co/web/sala-de-prensa/noticias/-/asset_publisher/LdWW0ECY1uxz/content/por-primera-vez-en-la-ultima-decada-el gobierno-reduce-la-deforestacion-en-un-17-

- iv ACT y PNN. 2017. Amazon Conservation Team (ACT) y Parques Nacionales Naturales de Colombia (PNN). Referencias a pueblos indígenas en aislamiento y amenazas sobre su territorio en la zona de ampliación del Parque Nacional Natural Serranía de Chiribiquete. Convenio 001 de 2013 suscrito entre la DTAM y ACT Colombia.

- v Finer M, Mamani N (2019) La deforestación impacta 4 áreas protegidas en la Amazonía colombiana. MAAP: 106.

- vi IDEAM. 2018. Subdirección de Ecosistemas e Información Ambiental (SEIA). Sistema de Monitoreo de Bosques y Carbono (SMByC). Alertas Tempranas de Deforestación. Boletín 13, Cuarto Trimestre de 2017.

- vii Agencia Nacional de Hidrocarburos ANH. Diciembre 17 de 2018. Mapa de Áreas actualizado (Mapa de Tierras) Disponible http://www.anh.gov.co/Asignacion-de-areas/Paginas/Mapa-de-tierras.aspx

- viii González, J., Cubillos, A., Chadid, M., Cubillos, A., Arias, M., Zúñiga, E., Joubert, F. Pérez, I. y V. Berrío. 2018. Caracterización de las principales causas y agentes de deforestación a nivel nacional período 2005- 2015. Instituto de Hidrología, Meteorología y Estudios Ambientales – IDEAM-. Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible. Programa ONU-REDD Colombia. Bogotá. En imprenta

- ix Botero García, Rodrigo. (2018). Frontera Agropecuaria en la Amazonía: La infraestructura de gran escala como motor de la ampliación en función de los mercados de tierras, energía y minería mundiales. Revista Semillas. Conservación y uso sostenible de la biodiversidad Derechos colectivos sobre los territorios y soberanía alimentaria N° 71/72 – Junio. 2-6 pp. Disponible en: http://semillas.org.co/es/revista/frontera-agropecuaria-en-la-amazonia-la-infraestructura-de-gran-escala-como-motor-de-la-ampliacin-en-funcin-de-los-mercados-2

- x Tierra Digna – Centro de estudios para la justicia social. Áreas estratégicas mineras. ¿qué son las áreas estratégicas mineras (AEM)? Disponible en http://tierradigna.org/aem/index.html

- xi Reporte Complementario N° 1763 – 14/08/2019 / COEN – INDECI y Reporte Complementario N° 1882 – 25/08/2019 / COEN – INDECI