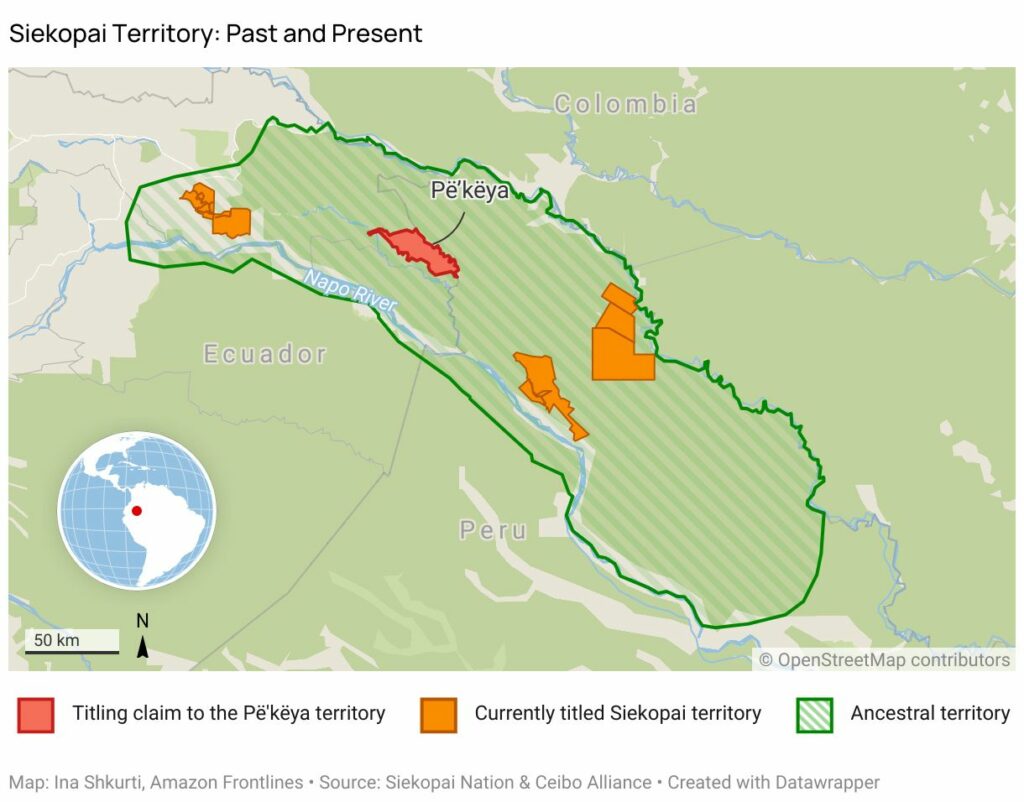

- For decades, Siekopai communities have fought to regain territorial rights over their ancestral homeland. This September, they’re taking the Ecuadorian state to court over its failure to uphold their rights.

- Lagartococha or Pë’këya, is the ancestral territory and spiritual heartland of the Siekopai people. In 1941, the majority of the nation was displaced during the Ecuador-Peru war.

- The rights of Indigenous communities to their ancestral territories is upheld by international and national law. Protecting this right through formal titles is crucial to protect communities and the ecologies they sustain.

Pë’këya: the heart of the Siekopai people

“Pë’këya is the soul of the Siekopai…There is everything that is important for a Siekopai person…that territory has power and value for what’s in it. Many stories I grew up with are from there and they are not only story, they explain who I am as a person and what my family is…I was denied the right to live there, and I see my children grow without understanding what it’s like to be a Siekopai, without a Siekopai soul because the soul is there.”

– Wilmer Piaguaje, Siekopai youth.

Indigenous territories are indivisible from Indigenous peoples’ past, present and future. Pë’këya, also known as Lagartococha, is the ancestral territory and spiritual epicenter of the Siekopai people. A knotwork of lagoons, islands, rivulets and rivers, it teems with life; the name itself, Pë’këya, refers to the sheer number of alligators living in the river.

From left to right: Siekopai community members stand alongside a Ceiba tree. A woman prepares a freshly hunted caiman.

Indigenous territories are indispensable for collective survival and the continuity of culture. Stretching over the borders of Ecuador and Peru in the Western Amazon, Pë’këya is the nucleus of Siekopai spirituality, memory, and knowledge. A space of mobility, connection, rituality, and cultural education. A realm of inestimable cosmological, mystical and historical value. A source of medicine, construction materials and foods. As Siekopai leader Justino Piaguaje notes, “[Pë’këya] is our territory, our blood, our birthplace, the basis of our worldview”’

Lagartococha is close to the sacred site of Ñañë-Jupo, the waterfall where the Ñañë-Paina God lived, and a site of proximity to the Ñañë-Siekopai, the mythic beings that hand down the legacy of Siekopai culture, give meaning to Siekopai life and allow for Siekopai people to feel, think and act as Siekopai.

“Pë’këya is the most sacred part of the territory, it holds my umbilical cord and the bones of my father, my mothers, and my grandparents. There I started the trails of the journey towards the full wisdom of the Siekopai, undisturbed, until the first intruders and strangers came to our lands to spread terror and diseases…” – Don Cesario Piaguaje, Siekopai traditional leader & shaman

Pë’këya is a space of exceptional biodiversity even within the Amazon, the world’s most biodiverse forest. Bio-cultural memory – the practice of protecting the library of life, nourishing it, and learning from it – is central in Siekopai culture. Siekopai ethnobotanical and ethnobiological knowledge is renowned and regarded as one of the most important in the Americas. Pë’këya is the nucleus of this understanding, home to unique species and environments that can only be found there. Each seed, each species, each being – is a summary of a relationship, a history of experienced interaction.

These beings – concentrated in Pë’këya – are indispensable for Siekopai architecture, spirituality, nutrition, and healthcare. The Wankuneo (aniba) trees, crucial for building the roofs of the tuikë (maloca, spiritual house), or for obtaining the insect-repellent wood necessary for homes. The yatzo, used for making bowls and other ceramics. The guazay mangrove, used for making fishing equipment and for healing fractures. The nutritious edible fruits of aunpoo, tsasa, or tara trees. Lagartococha’s unique topography allows for a high concentration of gosa (ungurahua palm), whose fruits are rich in nutritional value, and are used to help young infants grow. Elders such as Erodia Payaguaje travel multiple times a year to Pë’këya to harvest these fruits.

Leorvis Payaguaje, a Siekopai mother, paddles along the Aguarico River towards Lagartococha on the Ecuador-Peru border.

Pë’këya also hosts the multiple beings relevant for sacred yagé (ayahuasca) ceremonies, indispensable for centring and communicating with ancestors. The specific river fishes such as bunitya and pacu, which feed on fruits and flowers, that yagé drinkers must feed on to prepare for ceremony. The conoguako, wasoka, and cuje plants used for sacred incense, perfumes, and candles. The sojo tree, whose essence is mixed with resin from the wansoka tree (sorva), to be used to cleanse ceremonial houses. The Ëko plant, which grows on the lagoon shores, and is necessary for purification.

From left to right: Siekopai leader Justino Piaguaje helps to gather plants and tree barks in Lagartococha during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Accomplished herbalists experimented with different combinations of medicinal plants to develop an effective remedy, which helped community members overcome the virus.

Pë’këya, especially in the Kwiñajaira area, has been a site of medicinal provision, over the course of centuries of resistance to disease brought by colonisation. During the most aggressive periods of the COVID-19 pandemic, Siekopai community members followed the tradition of their ancestors, returning to Pë’këya to find medicines, both for their community and others, and to seek shelter. Oral memory recalled ancestors turning to particular plants during the time of the Spanish flu. Drawing on this remembrance, medicinal plants such as the toñajora or cinchona plants were collected, and their knowledge shared with many other Indigenous communities.

“Lagartococha represents me as a place…because here, the Siekopai people feel like a native people.” – Alfredo Payaguaje, Siekopai grandfather

In Siekopai cosmology, Pë’këya – through its waters, swamps, spirits, and beings that travel throughout – represents a sacred portal into the aquatic world and its ancestral wisdom. As 112-year old shaman and traditional leader Don Cesario Piyaguaje explains, “[For the Siekopai people] Pë’këya is the home, the abode of the aquatic world. It is what is known as great biodiversity, because there is a lot of water, trees, animals. In the cultural conception, biodiversity is made up of spirits that are procreating, and it constitutes a door, a way out of this to another world, the aquatic world.” This realm is also the burial ground for many Siekopai elders. As Maruja Payaguaje explains, “[Lagartococha] is the umbilical cord of my grandparents – that is why we want to return. It’s not a problem of lands, not of where to go live, it’s a question of spiritual essence, from [Lagartococha] we weave our relationship to other peoples.”

Siekopai youth paddle in a canoe in Lagartococha.

Historically, Lagartococha was a point of encounter, knowledge exchange and shared yagé ceremonies between different Siekopai families and communities, given its unique proximity to water, forest, and sky spirits. Since times of early colonisation, Pë’këya was also a space of refuge, accessible only through labyrinthine routes, to protect life and the continuity of Siekopai culture from white people and threats.

Indigenous communities need protected territories, for they offer communal protection. The Siekopai community today, with a population of around 700 people, are at risk of cultural extinction, resulting from forced assimilation and displacement. As Don Cesario Payaguaje notes, “it’s vital, the sacred territory of the Siekopai in Lagartococha, for young people to not stop being Siekopai and so they continue transmitting our culture from generation to generation. It is the territory chosen by our God Ñañë-Paina.”

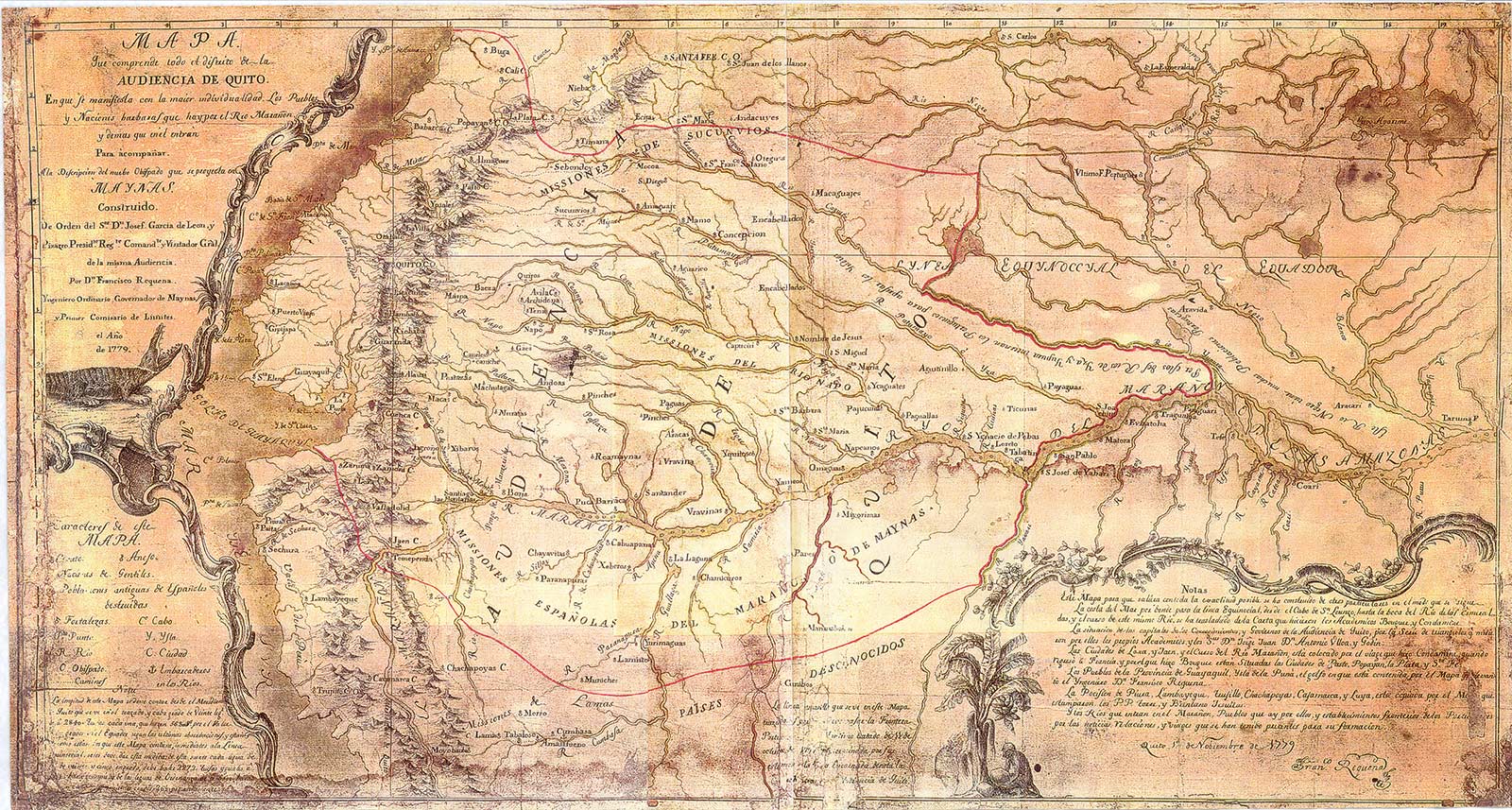

Yet for decades, the Ecuadorian state has refused to recognise and deliver an ancestral land title over Pë’këya to the Siekopai community. In a world governed by a Western conception of laws, where formal private property rights are supreme, juridical protection is the cornerstone for the protection of ancestral territory. Siekopai oral memory recalls that generations have lived in Pë’kë’ya for many centuries; old Spanish colonial maps from the Royal Court of Quito in 1779, which precede the existence of the Ecuadorian state, also note the presence of Siekopai in Pë’kë’ya.

1779 map of the Spanish military general Francisco Requena presented to the Royal Audience of Quito. The Lagartococha river is shown as the “Puquilla” river, a Hispanicized interpretation of “Pë’kë’ya”.

Part II: The drivers of displacement and oppression

Since colonisation, Siekopai people, like all Indigenous peoples across the Americas, have repeatedly been subjected to violent attempts to displace, dominate and suppress the community. Colonising missions, rubber corporations, warring governments, and most recently, attempts by states to create “protected areas” for conservation, have all sought to uproot centuries of Siekopai existence.

In the mid-1860s, Jesuit and Fransiscan missionaries, followed by rubber tappers, brought illnesses such as flu, smallpox and measles to Siekopai populations. Rubber plantations imposed enslavement and debt bondage, decimating the community.

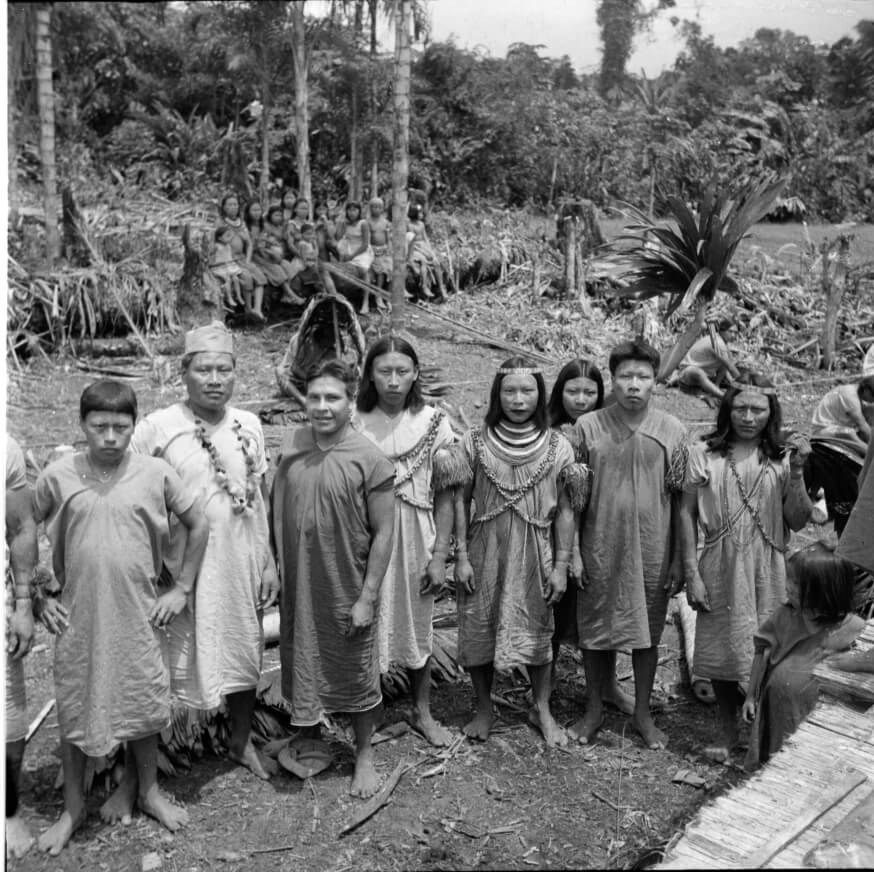

From top left to right: Siekopai community members in traditional dress; Siekopai men with instruments; Siekopai family members with an evangelical missionary, Orville Johnson; Siekopai family members receive copies of the New Testament translated into Paicoca language. Photos from the 1990s by Instituto de Lingüística de Verano

In 1941, war broke out between Peru and Ecuador. The ancestral territory of Pë’këya, located on the borderlands of both states in the conflict, was declared an area of “national security interest” and was swiftly militarised. Military encampments and outposts were established where there were spiritual houses.

The war was an enormous blow to the social-territorial fabric of the Siekopai nation, and their fluid borderless existence. Both national armies deemed the Siekopai nation as spies. A militarized border was erected between Peru and Ecuador, driving families apart, and uprooting the Siekopai nation from their home. Many families – siblings, cousins, parents, children – were split and splintered. Some would never be reunited; others would only see each other after decades.

Many Siekopai, according to the oral memory of elder Mariano Piyaguaje, fled their territory to avoid being conscripted into the war. Over the next decade the Lagartococha river would become a military supply line, and its shores would see periodic fighting. Displaced Siekopai communities were forced to settle far from their ancestral homeland, removed from the plants, animals, and sites that have given them life and clarity. Many of those displaced families remain today on depleted territories, surrounded by oil companies and palm plantations.

For decades, during and after the war, Siekopai tried to return to their homeland, only to face detention and abuse by military authorities. Yet even during the most violent and militarized periods, many Siekopai families risked their lives traversing hidden routes to constantly return to Pë’këya, to fish, gather food and conduct ceremonies.

“We are not fighting for a quantity of lands – it’s the area, it’s the place, it’s the spirit, it’s what someone as a Siekopai person can feel being there that doesn’t happen anywhere else, only there can a Siekopai feel free.” – Alfredo Piaguje, Siekopai grandfather

In 1979, the creation of the Cuyabeno Wildlife Reserve, a protected area in the northeast of Ecuadorian Amazon, brought another blow to Siekopai sovereignty. In 1991, it was extended to include Lagartococha. From 1992 onwards, Siekopai communities have been petitioning Ecuador’s Ministry of the Environment, to find an agreement for Siekopai families to return to Lagartococha. In 1998, the signing of a peace agreement between Ecuador and Peru, encouraged the Siekopai to intensify their efforts.

Part III: Struggles for Justice

For decades, the Siekopai have struggled for justice, demanding the Ecuadorian state uphold international law and Ecuador’s constitution, which recognise that ancestral territories are property and possession of Indigenous communities.

Siekopai leader Justino Piaguaje during a meeting with government officials from Ecuador’s Ministry of the Environment.

Why does proper titling and the protection of ancestral territorial rights matter? From the perspective of Western law – a land title gives communities juridical security before third parties. As Jorge Acero, an Amazon Frontlines lawyer collaborating on the case says, “it guarantees for Indigenous communities the peaceful stewardship of their territories.”

The right to ancestral property is intimately tied to other rights: the right to self-government, to autonomy, to food and medicine.

Lagartococha is today considered by Ecuadorian law a “protected area”, following a decision by the country’s Ministry of the Environment, taken without any prior consultation of the Siekopai people. Over the last decades, thousands of acres of Indigenous land, without consent, were designated “protected areas”. To this date, the Environment Ministry has not designated or handed over a single ancestral property title deed in a protected area.

The Ecuadorian state and especially the Ministry of the Environment is clearly culpable for ongoing violations of Indigenous rights, enshrined both in Ecuador’s Constitution and international law. The Ministry of the Environment has claimed it lacks the technical ‘instructive’, the detailed technical guidance on how to make an ancestral property title deed. But both international law and the Ecuadorian Constitution are clear: rights violations are not excusable by the absence of any technical guidance. In addition, technical guidance even for complex legal procedures, with the right political will, can be defined in a month or a few months.

In 2017, the Siekopai nation formally solicited the delivery of a title deed to an ancestral territory from Ecuador’s Ministry of the Environment. After delays from the Ministry, in 2019, the community presented a case at Ecuador’s Ombudsman around communal rights violations around the failure to deliver the title. The Ombudsman ruled in the community’s favor, urging for an urgent delivery of the property title.

Yet the Ministry of the Environment, despite this case being known for decades, despite being fully aware of the violations of rights, despite the formal request for a title being submitted in 2017, despite the Ombudsman’s ruling, has still failed to act.

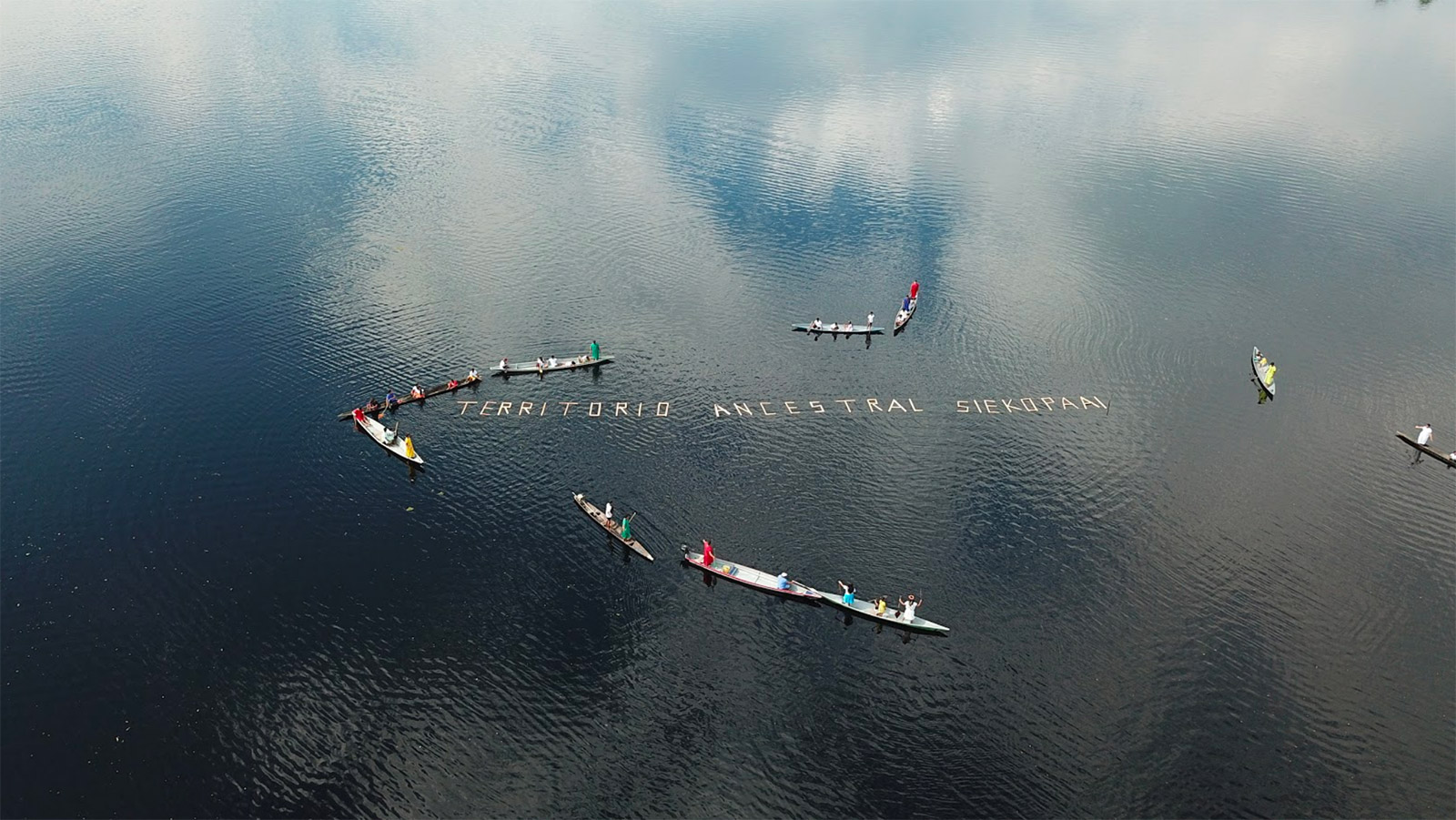

And so, yesterday, the Siekopai nation decided to take the Ecuadorian government to court over the violations of their right to ancestral property in Lagartococha, denouncing the state for its failure to protect their rights, an obligation outlined by international and national law.

Left: Siekopai people march towards the Provincial Court to file their lawsuit against the Ecuadorian Government, September 2022. Right: Five Siekopai children are plaintiffs in the lawsuit.

The legal claim to obtain a property title over around 104 000 acres has been grounded in a communal mapping process. Using cameras, GPS receivers, satellite imagery, aerial drones, and many other instruments, the community has collectively geo-referenced and documented the scope of their ancestral territory.

After centuries of colonial injustice, and 81 years since the war that forcibly displaced the Siekopai from Lagartococha, it is inadmissible for the Ecuadorian state to drag its feet on the delivery of territorial rights. The state’s actions and inactions have deepened the historic marginalization of the Siekopai nation and the systematic violation of Indigenous rights. Ancestral territorial rights are pathways to survival. Only by protecting their territory and guaranteeing Siekopai sovereignty, can the multiple rights of the Siekopai people be protected.

Part IV: International Implications

Juridical protection secures the rights of Indigenous communities to their territories before third parties. It is crucial for multiple reasons: for reasons of justice – communities deserve to have their rights respected; for reasons of protection, as formal titling can limit the possibility of encroachment by corporate interests taking advantage of unclear ownership; for reasons of cultural revitalisation and survival, as territorial protection is indispensable for enabling communities to create and recreate culture; and for ecological reasons, as titling is critical for protecting the Amazon, one of the world’s largest carbon sinks.

Titling is not a concession, but a recognition of ancestral links to territory, an acknowledgment that an Indigenous community is first in right because it was first in time. Titling and the right to territory remind us of the interdependence of rights. A territory is what enables a community to guarantee its physical and cultural survival. The right to life, the right to food, the right to medicine, the right to a spiritual relationship with land, and so many others – all fall under the right to a territory.

Siekopai elders and youth stand united to reclaim their ancestral heartland, Lagartococha.

To obtain the ancestral property title over Lagartococha is an essential step for Siekopai people to have guarantees over the spaces indispensable for their cultural persistence.

It is up to us to help shed light on the systematic violation of territorial rights, and put pressure on the Ecuadorian state to recognise the Siekopai’s ancestral territory, repair its historic abrogations of Indigenous rights, and take concrete actions to protect the relationships of communities to their territories. The struggle stretches to many other territories too. Over 3 million acres of Indigenous territory are caught up in Ecuador’s colonial and inept national park system, and still without title.

Through their struggle, the Siekopai hope to reclaim their ancestral land and set a precedent for dozens of other indigenous groups in Ecuador that have been “parked out” of their ancestral territories. The vitality of Indigenous cultures relies on the vitality of landscapes, and the strength of their mutual protection. Indigenous communities the world over are the primary guardians of bio-cultural memory and diversity. Territory – where memory meets land, where culture is indistinguishable from nature – is sacred and worthy of protection, everywhere.