For elders living in Waorani territory of Ecuador’s Pastaza Province, a ½ million acre roadless wilderness still untouched by the perils of oil, mining and logging, the forest contains nearly everything that is needed for a happy and healthy life.

▼ Here, Pava Yeti, an elder from the village of Kiwaro, makes a basket from palm leaves for harvesting and carrying wild fruits, such as petomo (ungurahua) and nontoka (peach palm).

Woven together by hundreds of miles of trails that connect birthplaces with burial grounds, gardens with villages, hunting camps with fishing holes, plant medicines with sacred sites, and backwoods creeks with big water rivers, Waorani elders know every nook and cranny of their immense rainforest home.

In the Oil Fields of the Amazon

Further to the east however, decades of oil extraction have converted thousands of acres of ancestral hunting grounds, fruit orchards and sacred sites into a patchwork of oil fields, logging camps, roads, and colonist settlements.

► In this picture, on the edge of Yasuni National Park famous for its rich biodiversity, a family of Waorani from the Via Pindo oil road walk back to their village along pipelines to avoid the hazards of speeding oil-company 18-wheelers.

And further to the north, in the borderlands with Colombia and Peru, more than a half-century of oil operations and colonization has devastated the ancestral lands of the Kofan, Siona and Secoya peoples.

▼ Here, Emergildo Criollo, a Kofan leader, recalls the first time he saw the oil company helicopter arriving in his people’s ancestral land. “Since then, the oil company has brought nothing but sickness and death to our people,” he tells Nemonte Nenquimo, leader of the Waorani people of Pastaza.

Upon arriving at an oil platform outside the industry town of Shushufindi in Ecuador’s Amazon Waorani women sing to the oil well: “We walk lightly in the footsteps of our ancestors, we will not let you into our land.”

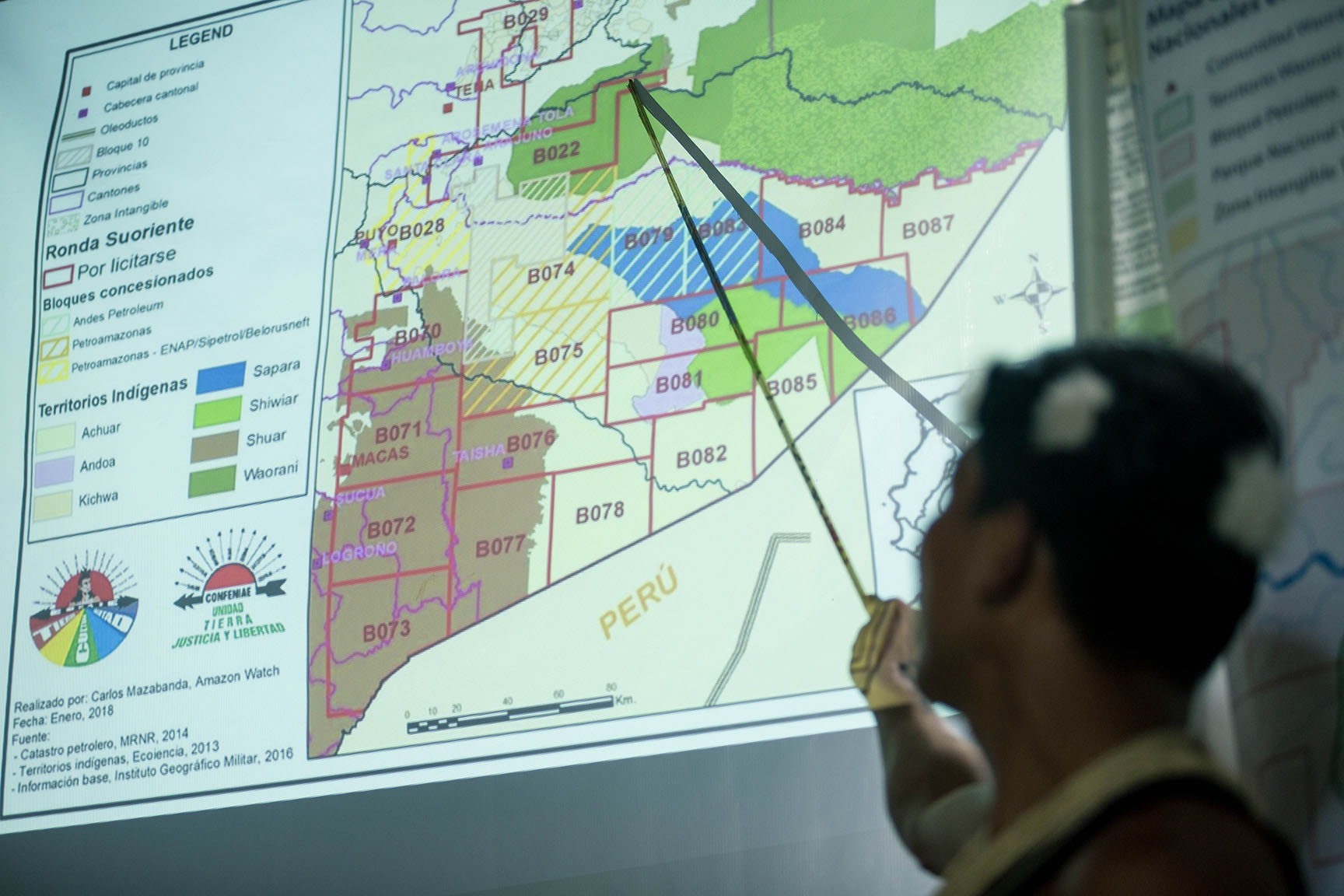

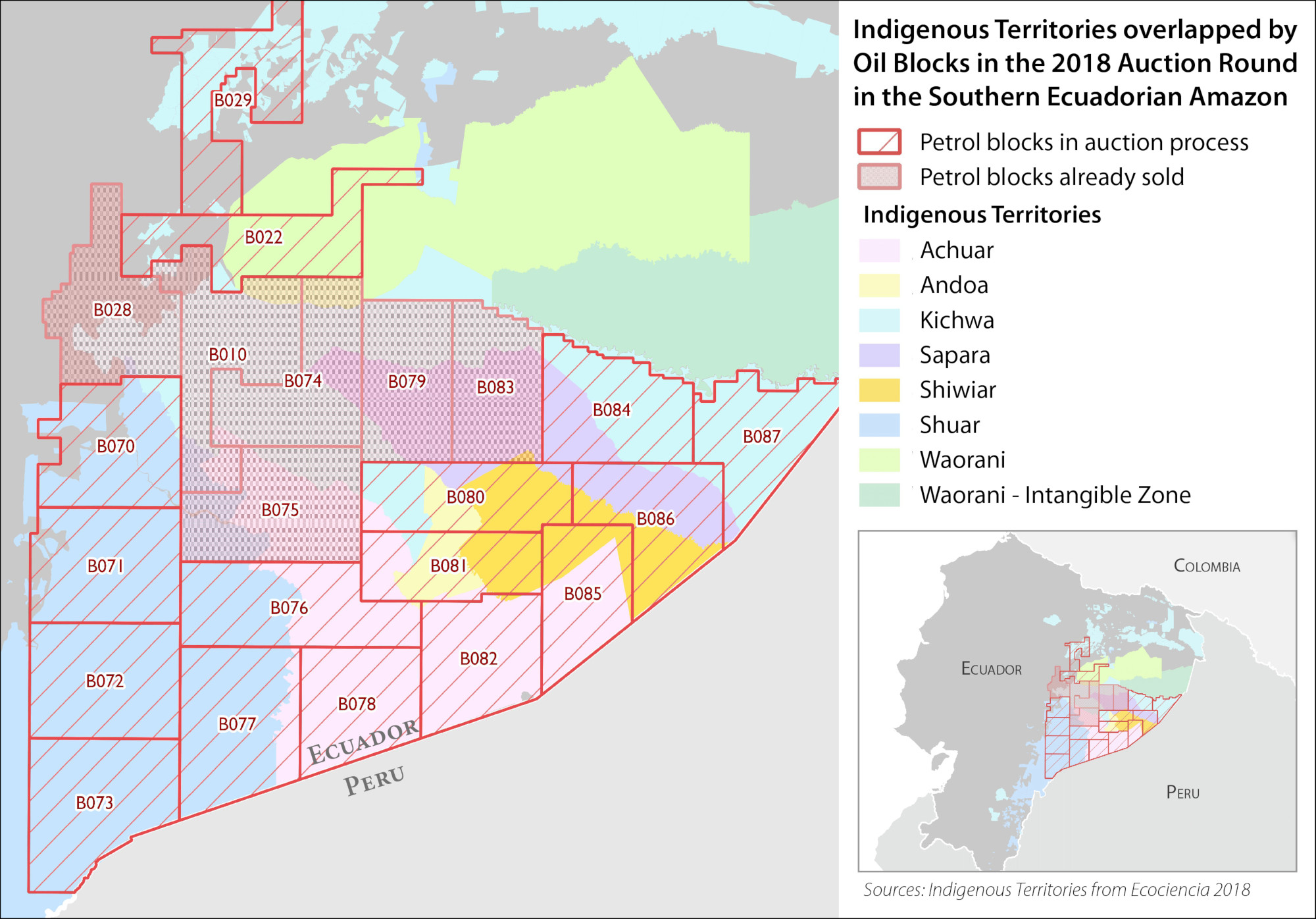

In 2012, the Ecuadorian Government announced plans to auction over 7 million acres of indigenous lands in the southcentral amazon to the oil industry.

Included in the oil auction was the newly denominated “Oil Block 22”, a half million acres of primary rainforest that the Waorani have called home for centuries.

Despite a slick government sponsored campaign to promote investment, many oil blocks, including Block 22, were not successfully sold at auction. Oil investors cited “risks” associated with community opposition and unattractive financial terms.

However, for the Waorani the “failed” oil auction was a warning. And a call to organize.

► Here, Omene Iwa, from the community of Tzapino tells how his ancestors defended the land with spears.

For Waorani elders, the current threats are too great to confront with spears alone, and so the youth must find new ways to defend their territory against unrelenting global pressures.

▼ In this photograph, youth leader Oswando Nenquimo reads a message to the Ecuadorian Government:

“We do not recognize what the government calls Oil Block 22. Our forest homeland is not an oil block. It is our life.”

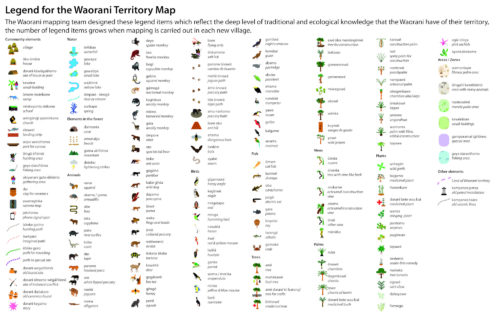

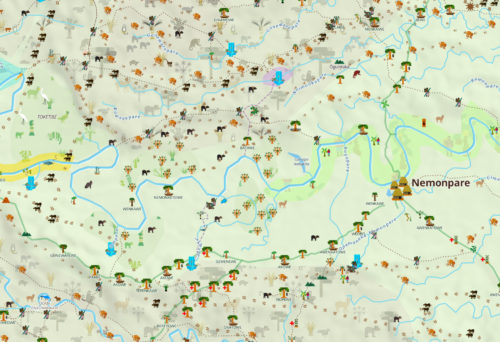

As a strategy of resistance, from 2015-2018, Waorani youth and elders set out to document and demonstrate life in their territory by creating a “living map” of their connection to the land, using GPS, film, camera traps, drones, and a customized mapping program that allowed them to work offline in remote forest.

Whereas the maps of oil companies only show petroleum deposits and major rivers, the maps that the Waorani created tell the story of their people’s relationship with the plants, the trees, the water, and the animals.

▼ Their maps identify historic battle sites, ancient cave-carvings, jaguar trails, medicinal plants, animal reproductive zones, important fishing holes, creek-crossings, and sacred waterfalls.

▼ In this photograph, school kids in the village of Nemonpare display their drawings of what they like most about life in the forest.

In 2018, the Ecuadorian Government announced renewed plans to auction million of acres of the southcentral Amazon to the oil industry.

▼ Here is a map illustrating the 16 proposed oil concessions, and their overlap with the ancestral territories of 7 indigenous nations.

“Oil Block 22” was once again up for sale to the highest petrol company bidder.

▼ In a public hearing in the village of Nemonpare, the Ecuadorian Human Rights Ombudsman takes testimony from youth and elders in preparation for the lawsuit.

Dozens of hours of interviews revealed that the government’s “consultation process” relied on time-tested tactics of manipulation and deceit, and was designed to keep Waorani villagers in the dark about the potential impacts of oil operations in their territories.

− Wina Boyotai from Kiwaro ►

− Oswando Nenquimo from Nemonpare ►

▼ Here, in the community of Nemonpare along the Curaray river, villagers prepare banners to take to the city to defend their rights and make their voices heard.

Victory for the Waorani

On February 27, 2019, hundreds of Waorani villagers from “Oil Block 22” marched to the courthouse in the Amazonian frontier town of Puyo to file their landmark lawsuit against the Ecuadorian government. ►

▼ In these photographs, Waorani women lead the march to the courthouse.

Many indigenous peoples from across the Amazon traveled to support the Waorani peoples’ historic fight to protect their lands from oil drilling. ▼

▼ In this picture, Nemonte Nenquimo, President of the Waorani Organization of Pastaza, carries the lawsuit in her hands, as Amazon Frontlines lawyer, Maria Espinosa addresses a crowd of supporters.

▼ In these photographs, the Waorani enter the courtroom to face off with the Ministry of Hydrocarbons, the Ministry of Non-Renewable Resources, and the Ministry of the Environment.

Photography was not permitted during the court proceedings.

▼ On April 26th, just hours before the landmark verdict in the Waorani trial was announced, Nemonte Nenquimo addresses a crowd of supporters and media on the front steps of the courthouse. “No matter what the court says today we will not let oil in our lands. Our land is not for sale!”

▼ Here Nemonte Nenquimo shares details of the historic verdict at a press conference outside the courthouse. The three-judge panel ruled that the Ecuadorian government had violated the Waorani’s rights to prior consultation and self-determination.

▼ In these photographs, the Waorani joyously march through the streets of the Amazonian town of Puyo during a torrential downpour. The court’s ruling immediately halts the government’s plans to sell their land to the oil industry, and sets a precedent for other indigenous nations to do the same.

Back to the Forest

After the historic court ruling whichprotects a half-million acres of their ancestral land from oil drilling, the Waorani returned to their forest homes.

And drank from the freshwater creeks.

And enjoyed the beauty of the waterfalls.

The Waorani’s landmark legal victory protects their ancestral homeland from oil and sets a powerful precedent for other indigenous nations to do the same, but this watershed moment could be snatched away in the next two months by a legal appeal. The Ecuadorian judicial system is not immune to political influence, especially with millions of acres of “untapped oil reserves” at stake and the Government’s keen interest in undoing this powerful legal precedent for indigenous rights.

We must seize the momentum, and turn national and global attention into an even bigger victory for indigenous peoples, the Amazon and our climate.