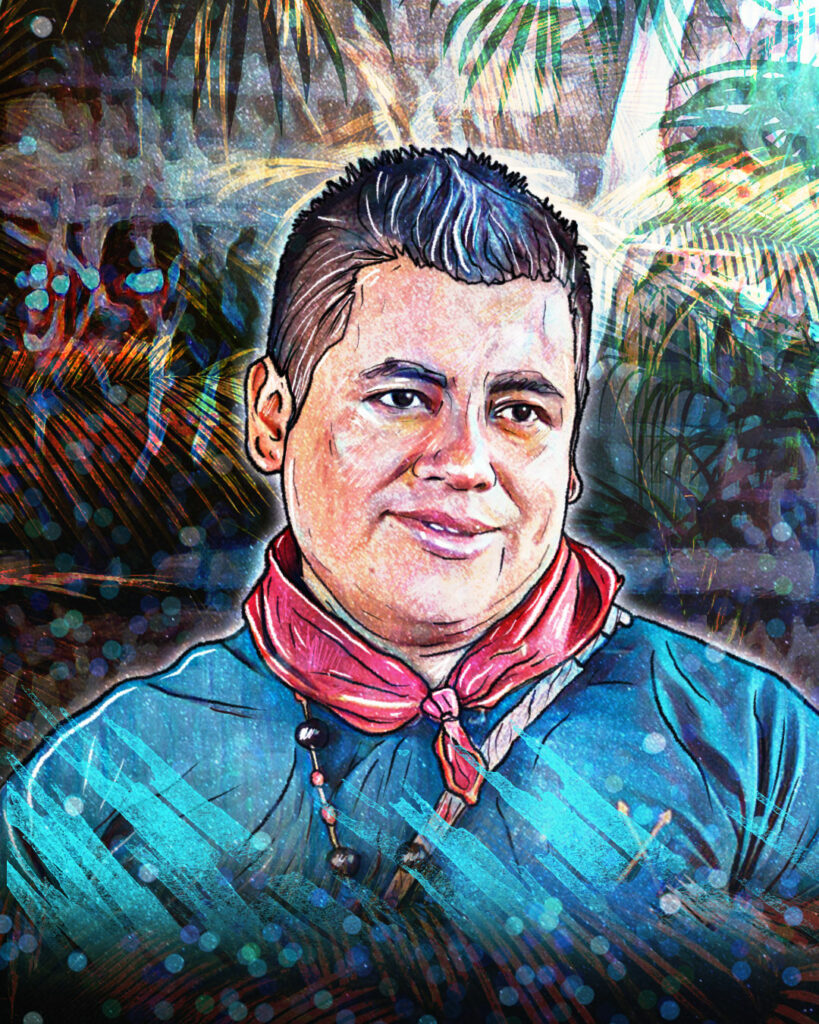

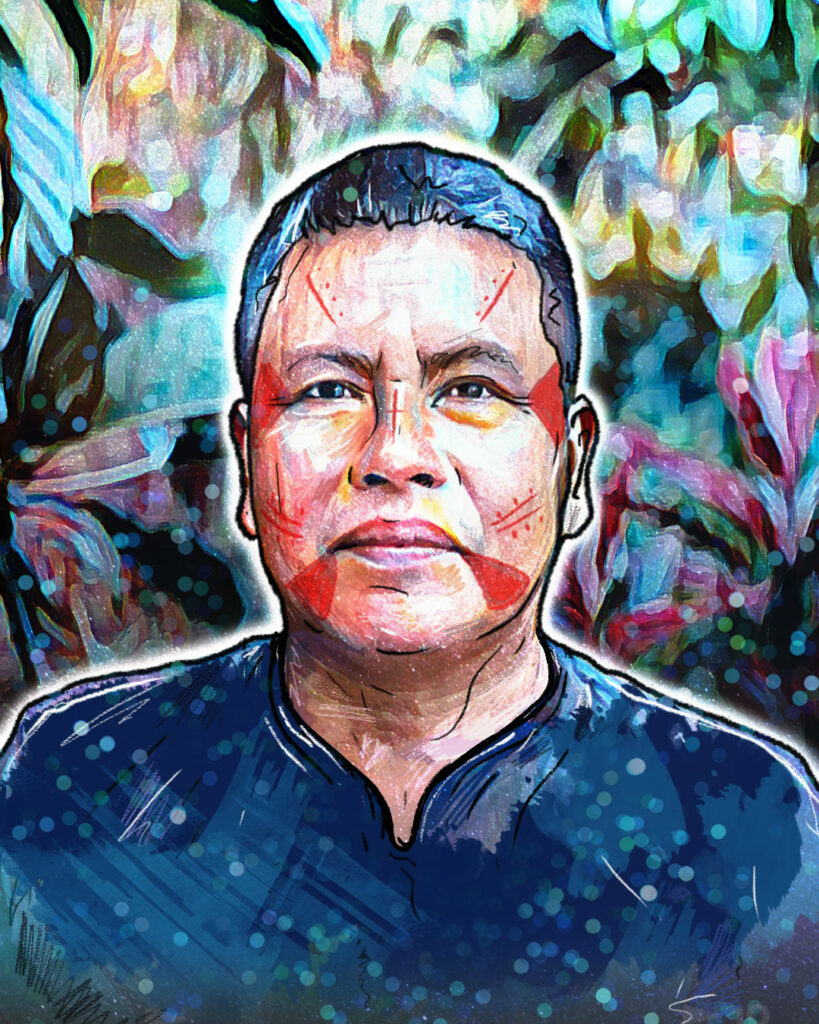

As a teacher in Siekopai communities, Wilmer Piaguaje wanted to make sure that the boys, girls and young people he educated did not go through the same difficulties he experienced as a child, and that they could recognize their culture. Today, Wilmer is both the education leader of the Siekopai Nation, and through Alianza Ceibo he also coordinates the community-led education initiative for his nation. His work seeks to consolidate learning spaces within communities that prioritize Siekopai culture so that girls and boys can live it with pride.

In this interview, Wilmer narrates his own educational experience and that of his father, as well as the process and needs involved in implementing Siekopai community-led education.

Q: What was the education you received as a child, how do you remember it?

A: In our small school, we first had a strict teacher, somewhat militarized, who had a civic and patriotic way of thinking towards Ecuador, not for the Siekopai Nation. He taught us about colonialism. His biggest concern was that we knew how to read, write and do mathematics.

The second teacher we had was Pablito. He was from the community, he graduated from the Limoncocha Institute. We had more confidence in him. He had that mindset of teaching more about community work, participating when we had mingas (communal encounters to come together around shared labor), even if it was just for a few hours. He took us to the meeting that was held by our community. That influence was good, to understand how we are and who we are, at least for me, it represented growth.

“What traditional education has given us is good, such as knowing how to read, write, and technology; but no more. It does not have in-depth knowledge of the Siekopai Nation, our own teachings. “The proposal of community-led education is based in cultural survival, in a worldview, in spirituality.”

Q: What level of education was there in the community and how did people continue their studies?

A: In my community, we could study between first to sixth grade in school. To continue my studies I had to look for a place to stay, because we had to travel by motorized canoe for three or four hours to get to Lago Agrio, Coca, Limoncocha or Shushufindi to study. That’s why my dad looked for a boarding school for me and took me to the Limoncocha boarding school, even though he himself had suffered a lot living at the boarding school with the Catholic missionaries in Nuevo Rocafuerte.

Q: Tell me a little about the education your father received?

A: Where my father lived on the banks of the Aguarico River there was no place to study. At that time, the priests from Nuevo Rocafuerte arrived and offered my grandfather an education for my father. My grandfather rowed him for two days in a canoe until he reached the Napo River and left my father at the boarding school. He suffered a lot there in the new environment. He could not speak Spanish. The treatment was very harsh. He tells us that they had to eat food that he was not used to, and at certain times, and so many portions, and if he did not eat, he received punishments or tasks that were too harsh. For any simple thing, they received punishment. He was forced to learn the masses and all that religious stuff. And that was quite intense he said; he didn’t like that at first, but as time went by, he started practicing Catholicism.

Q: And what was your experience with the boarding school?

A: Still quite critical, the first suffering was the food. Then, being with other people that I didn’t know. There were so many of us and all at different levels of education. They had the little ones like baby chicks, we all lived in a single pavilion. It was difficult for me to understand – we had to have everything first in Spanish, second in Kichwa and third in English. I was traumatized by the linguistic issue and told myself, well, we have to learn! Sometimes I didn’t even know what language to answer in, because there was so much linguistic interference. I would start speaking in Kichwa and end up speaking in English.

During the final years, in the fifth course, we were trained as teachers. We had as a subject the model of bilingual intercultural education – MOSEIB – where we had to learn the curriculum. That was a pretty good orientation for the community, because once we had finished, we had to impart the material to the children.

They gave me the opportunity to be a teacher and by now it was a different way of teaching, not like my first teacher who taught by shouting, with a ruler. We wouldn’t do that anymore! We came with the thought of singing, playing. The young people I taught now thank me as they learnt more with me than with other teachers; they learnt to read, write and understand the community organization, our rules. Some of them are now leaders.

Q: Currently, how does the education provided by the Ministry of Education work in the communities?

A: In the last ten years the curriculum has been completely changed; the teachers have to teach this and that, at certain times and certain subjects. We used to have community gatherings, we would go out to teach how to observe a real tree, not just draw the branch, and not just the structure of the tree, but what benefits it has. Those things have been taken from us in recent times. The Siekopai language is a subject, but it is not just about grammar, but about the sense of where and who we, the Siekopai, are. That is what we are working to change with community led-education.

Q: How is the community-led education proposal different from the education offered by the Ministry of Education?

A: What traditional education has given us is good, such as knowing how to read, write, and technology; but no more. It does not have in-depth knowledge of the Siekopai Nation, our own teachings. The proposal of community-led education is based in cultural survival, in a worldview, in spirituality

From the Siekopai worldview: the subsoil, the water, the terrestrial space where we live, all form part of the nine spaces of Siekopai cosmological knowledge. Children must learn, for example, topics such as: what is the subsoil for Siekopai people? What spirits does it have? Where do we come from? From a Western perspective, what do you have there underground? There is oil, silver, gold, there is groundwater. Children must have these two pieces of knowledge, that is what we want in the curriculum: that they do not only learn what is from the West, and that they do not lose what is their own.

“I feel that the work of community-led education is the main basis to sustain the existence of the Siekopai Nation. We are defending and sustaining our ancestral knowledge.”

Q: Are the elders also going to be involved?

A: They are part of our teaching. The education we propose doesn’t envision only a teacher, now we are involving the elders, the wise community members to help us with the guidance of children, the transmission of stories, the taking of the yocó, respect based on cultural practice. These are all things that we have to apply in educational centers.

Q: Why is it so important that the Ministry of Education approves this framework?

A: The Ministry has to understand that ancestral knowledge is learned in practice. The Ministry’s curriculum says that children have to spend 5, 8 hours in classrooms. We have found in the diagnoses that there are certain hours when boys and girls are simply not learning, because the Siekopai way of learning is very different.

More than that, no other type of framework was possible before because there were no materials, there was no path, no guide. What is happening now with the teachers is that they only have texts from the outside. How does a teacher create a class about the Siekopai Nation if they don’t have materials? So you have to work on texts, on books based on your own curricular framework.

What we ask of the Ministry is to allow a community-led autonomous administration of the Siekopai Nation. Regarding the materials, we do not want them to give us already made ones, but rather that they provide the financing so that we as a Siekopai nation develop our own materials, so that the technical pedagogical teams can develop recreational material and elaboration of the texts. We want to work on all of this in the territory. We do not want them to bring us materials from somewhere else.

Q: In what way do you think that community-led education is linked to the defense of the territory?

A: What negative influences have we received from the West? Colonization, oil, palm cultivation. All this that has been done on a large scale, how has it affected us? Or perhaps, how could it benefit us? These are things that we have to teach our children so that they respect their territory and take care of it as the only thing we have. Otherwise, the territory will be seen as a business, or as an opportunity to extract natural resources that are not eternal. We should teach about climate change, and from our ancestral knowledge, the spirits that trees or animals have. If we do not help them understand that, they will just see another animal, another tree, and we do not want that. That is why community-led education helps a lot in the defense of the territory.

Q: How do you imagine the children who have studied with community-led education will be like?

A: Young people who leave to study at school and university, if they go with Siekopai knowledge already planted in them, they will have that connection with the territory and will want to return and not get lost. They will not say “I don’t know who I am and where I am.” Wherever they are, they will have that Siekopai identity in their heart and in their daily practice.

I feel that the work of community-led education is the main basis to sustain the existence of the Siekopai Nation. We are defending and sustaining our ancestral knowledge, because otherwise, as many anthropologists have told us, in 30 to 50 years, the Siekopai are going to disappear. We don’t want that.

May the teaching practices through Yagé and Yocó not be lost. May the children begin to understand that they are transmitters of culture, so that their children and grandchildren will also be the same. It is a chain of life that we are building through this Siekopai education.

We are already developing two pilot programs in which two educational centers will have their maloca (ceremonial house), where the little ones will be able to share the songs, the weavings, and all that we have planned.

Q: What message do you want to send to the world about self-education?

I would invite them to join and visit the territory so that we can work together in different technical areas, so that they know how they can contribute. We are here to work, fighting for existence.