Two scientific articles recently published by Amazon Frontlines staff are contributing to a growing body of academic literature, demonstrating how and why Indigenous peoples are leaders when it comes to conserving biodiversity and defending against climate change.

Indigenous Peoples, a unifying term for an immense diversity of cultures and values, live in all corners of the world. Through the plurality of their practices, understandings, and relationships with their territories, they also happen to hold the keys to many of the solutions to the crises we are facing. Not only do their ancestral territories overlap with the world’s remaining intact forest landscapes and key biodiversity hotspots, their ways of life, governing institutions and land rights contribute to lower rates of deforestation, increased carbon storage, and higher levels of biodiversity compared to lands managed by either government or private entities.

It is perhaps fitting then that scientific studies are increasingly finding that Indigenous Peoples are the most effective at conserving biodiversity compared to ‘western’ forms of conservation, such as protected areas (ie. national parks). The key to this effectiveness is the intimate relationship Indigenous communities have with their territories and the diversity embedded within ancestral knowledge. This integral relationship encompasses elements of the ‘spiritual’, historical, and most importantly the day-to-day reciprocal connection with nature (material and immaterial) for meeting the basic necessities of life all of which was acquired over thousands of years of ancestral presence and learning. The knowledge of landscapes and ecosystems, such as forests, provides the basis of this connection, generating its value and consequently its protection.

This relationship, system of values and knowledge are represented through their governing institutions: systems of interacting, deciding and regulating which ensure harmony is maintained between the community and the living territories they call home. Through autonomous governments, councils and other customary decision-making processes, Indigenous communities come together to discuss and formulate strategies that allow them to adapt and respond to the threats they perceive and experience on a daily basis.

Despite living on the frontlines of climate disruption and threats from extractive industries, Indigenous communities continue to lead responses to the ecological crisis, all while receiving little to no financial support, and being actively marginalized by global institutions and policies. A wealth of evidence now shows this must change, with direct funding, tenure rights and recognition for Indigenous Peoples and local communities representing the major routes to effectively address biodiversity and climate crises.

A typology of Indigenous peoples’ and local communities’ roles in conserving biodiversity

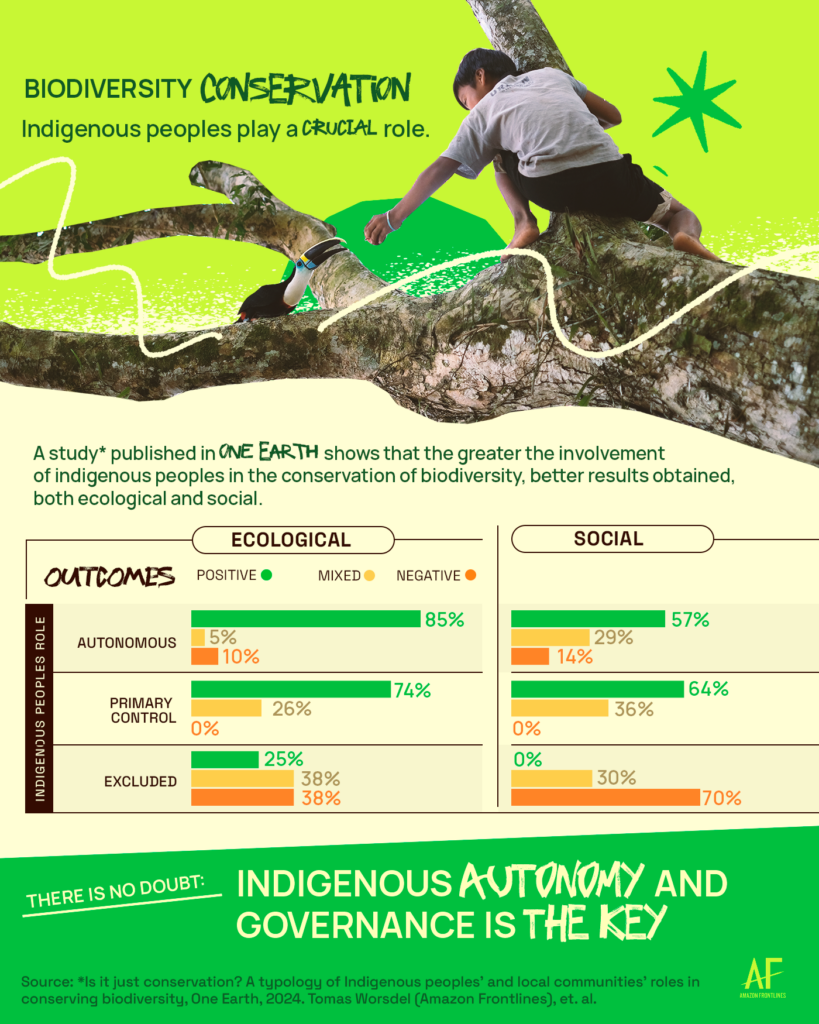

It is this current reality, of systematic exclusion despite exemplary leadership, which motivates our work as researchers and coordinators at Amazon Frontlines. Our first study, drawing on nearly 650 scientific articles, was guided by two principal questions: How are Indigenous Peoples and local communities involved in conservation? How do their influence, knowledge and actions contribute to conservation efforts?

What our research found was that conservation success is fundamentally linked to the quality and level of Indigenous engagement. When Indigenous Peoples are excluded or involved only as participants or stakeholders, they may find themselves unable to influence decisions of great importance to their daily lives. They may also have their rights violated, or be denied access to lands of cultural importance. In these cases, the majority of ecological results are far from effective or even counter-productive.

In contrast, when Indigenous Peoples have greater control and freedom to live according to their cultural values (cosmogony), ecological success goes hand in hand with improved social outcomes. Communities can freely live and defend their territories in accordance to their spiritual and cultural values in order to live in harmony, strengthen their institutions, equitably share benefits improving their quality of life, both individually and collectively. These findings echo previous research demonstrating how positive outcomes for both collective well-being and conservation come from cases where Indigenous Peoples play a central role in conservation decision-making.

Reviewing 50 years of conservation science: Knowledge production biases and lessons for practice

Our second recently-published article highlights another profound issue in conservation science: the production of conservation knowledge. Analyzing the same database mentioned earlier, we uncovered strong biases in knowledge production, suggesting a persistent colonial power dynamic in conservation science as well as important potential conflicts of interest. Our findings show that knowledge production about the Global South is largely produced by researchers in the Global North, who represent 64 % of lead authors. Additionally, issues of independence are prevalent in 14% of all scientific studies about conservation and crucially this suppresses the otherwise clear relationship between the leadership of Indigenous and local communities and successful conservation.

The production of scientific knowledge can be extractive and even dismissive of Indigenous knowledge. Equity in conservation practice should be advanced not only for moral reasons, but because it can enhance conservation effectiveness and this extends to how conservation knowledge is being produced.

Rethinking the production of knowledge on conservation requires us to value knowledge in its plural forms. Ancestral knowledge rooted in territories is what holds the key to the abundant positive climate and biodiversity impacts occurring within Indigenous territories around the world. This is why the protection of ancestral knowledges, autonomy of the governing institutions and the territories they rely on is at the core of our work here at Amazon Frontlines. Safeguarding Indigenous ancestral knowledge means defending Indigenous rights, recognizing and titling Indigenous territories, protecting traditional education systems, and ensuring Indigenous sovereignty in all its forms and governing institutions.

Achieving all these is a daily struggle, given constant extractive threats to Indigenous territories, and the continuous exclusion of Indigenous groups from national and international policy spaces. So what does taking back control and countering these power asymmetries in the conservation space look like?

Power asymmetries

Our work at Amazon Frontlines reflects the findings in these two papers. For example, the Siekopai Nation and their active Indigenous guards are in the process of completing a biodiversity base-line study which intertwines their ancestral knowledge with scientific methodologies. This study will form a basis and guide for their territorial governing processes as well as create a set of rules for cohabiting with the biodiversity they share their territories with, and coordinating actions to ensure impacts of an encroaching extractive world do not cause disharmonies in their territory. This is an example of how Indigenous communities can apply an active and effective form of territorial defense and biodiversity conservation when their governing institutions and territorial rights are respected, upheld, and freely practiced under their cultural authority.

We must think beyond the common buzzwords used in the global conservation space, such as “participation”, “community-based” or “co-management”. These might sound good, but they can have drastically different connotations depending on the type of relationships conservation actors have with Indigenous Peoples, especially when a community or nationality does not possess a land title. When we hear about Indigenous participation, we need to ask: who is participating in what? Who is doing the participating, and who is setting the agenda that requires participating in? Are specialists (biologists, ecologists, conservation practitioners) participating in an Indigenous agenda, or are the Indigenous Peoples participating in a project already pre-defined by a western agenda?

Rather than participation, Indigenous organizations and communities talk about “governance”. Governance and management are not the same thing. Management incorporates the actions needed to achieve certain goals or objectives while governance includes the decision-making behind setting those objectives, who makes them, how they are made and under what authority and legitimacy. If an agenda is made by a mission-oriented conservation organization with aspirations to provide a path whereby Indigenous Peoples can participate in its execution, it is ultimately not supporting indigenous autonomy to govern their ancestral territories through their institutions, cosmogony and authority.

Our two new scientific articles, as well as previously published papers, go further to suggest that conservation is most effective for both people and nature when Indigenous Peoples are setting the agenda, in charge of governance and recognized as leaders. Governance works when it is protected by a string of rights such as territorial sovereignty and autonomy.

It is high time for the implications of global research to be taken seriously by institutions across the world, from academia to politics. States have agreed to the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, which aims to increase the global coverage of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures to at least 30 percent by 2030. This goal, and the many other international agreements on climate change, rely on the work, knowledge, and expertise of Indigenous populations. A safe future for all of us on this planet relies on whether Indigenous governance, rights, and knowledge will be honored and recognized around the world. We should be wary of conservation initiatives that do not support the political processes that entail territorial autonomy, governance, and the titling of ancestral territories.