That same day, further inland, heavy rains pounded the Province of Esmeraldas, which is located on Ecuador’s northern coast and stretches from beaches into dense tropical forest. The rains led to a landslide, which caused the Trans-Ecuadorian Oil Pipeline System (SOTE) to break. It took hours for state oil workers to detect the rupture and shut off the pipeline, during which over one million gallons of crude oil gushed into the Esmeraldas River.

The oil spread fifty miles downstream before reaching the ocean, affecting two other rivers (the Caple and Viche), nine beaches, and more than 700 acres of farmland, according to Petroecuador, the state oil company. An estimated half a million people were left without drinking water and exposed to toxic gases; it was a humanitarian crisis.

That crisis would only deepen as the days and weeks went by. With the rivers, surrounding lands, and coastline all poisoned, thousands of people lost their jobs; tourism was cancelled, fishing decimated, and livestock killed. The oil reached a mangrove wildlife reserve. Along the more than fifty miles of the oil spill, thousands of species and entire ecosystems faced extreme peril.

A few weeks after the spill, Héctor Pincay told a reporter from Mongabay that he’d lost his crops, his livestock, his ability to work, and his food source. He’d spent hundreds of dollars on doctor’s visits and medicine to regain his sight. His life will never be the same. And Pincay’s story is just one of many, a glimpse into what hundreds of thousands of people face each time there is an oil spill, because this is not an isolated incident. This is oil extraction in the Amazon.

Video: Thomas Worsdell

Reckless Oil Extraction

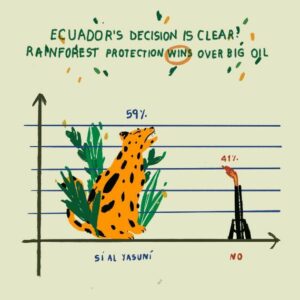

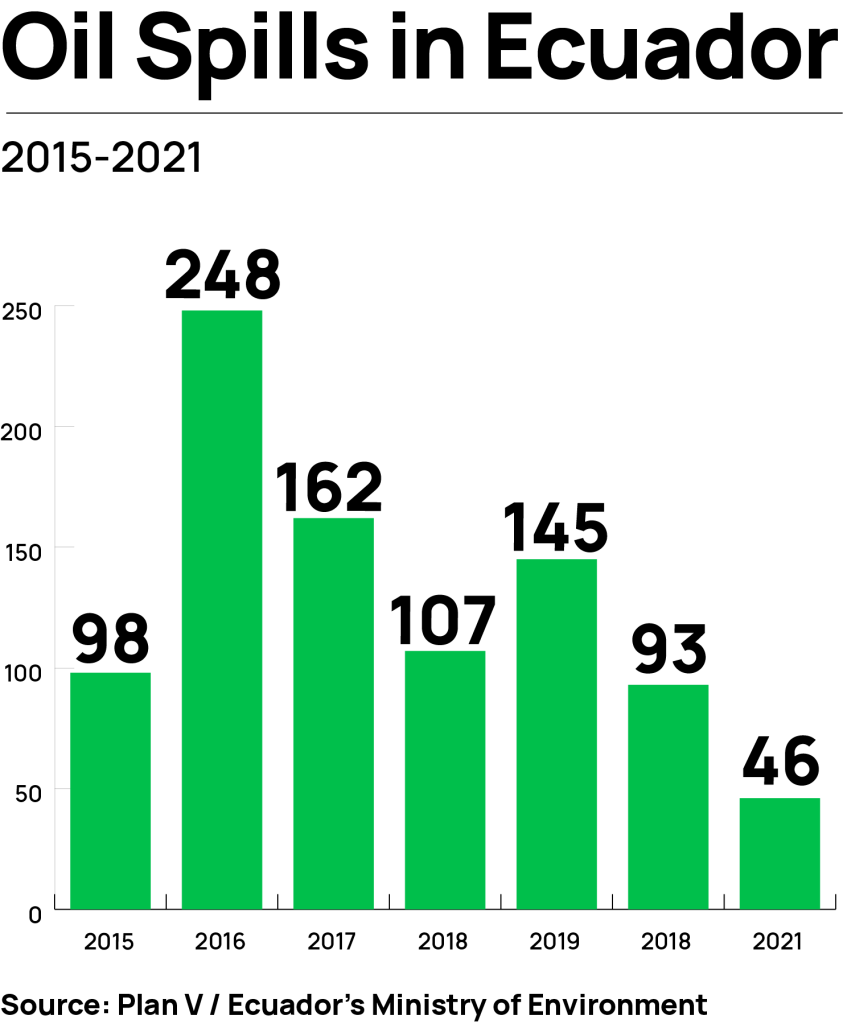

Between 2015 and 2021, there were at least 899 oil spills in Ecuador alone, the smallest of the oil-producing Amazonian nations. That’s two spills a week. The SOTE pipeline alone has had at least 77 oil spills in its 52-year history of operation, and those are only the spills that have been officially registered. The number doesn’t include the deliberate dumping of oil and wastewater on roads or the smaller spills across the 310 miles of the pipeline that don’t make the headlines. Even so, just taking into account the official number, the SOTE has dumped at least 32 million gallons of oil into pristine rivers, rainforest lands, and coastline; that’s almost three times as much oil as what was spilled in the Exxon Valdez disaster, which was one of the largest oil spills in U.S. history.

And oil spills are just one problem. Oil companies in the Amazon destroy ecosystems to build roads and pipelines, they routinely dump toxic waste in rivers and bury it underground where it leaches into the aquifers, killing plant and animal life, and filters back into the rivers. Texaco, one of the first oil companies to operate in the Ecuadorian Amazon, famously left behind a legacy of contamination—spills that the company never cleaned, toxic waste that Texaco, which was later purchased by Chevron, dumped, hid, and lied about—that led to a decades-long lawsuit and destroyed countless lives and vast expanses of rainforest. And now the Ecuadorian government and Big Oil want to do it all again, to double down on this devastating legacy. They are drawing up plans to expand oil operations across 8.7 million acres of old-growth Amazon rainforest, home to seven different Indigenous nations, including the last Indigenous Peoples living in voluntary isolation in Ecuador. What will this sacrifice of a vast, irreplaceable, invaluable natural world, and the people and cultures that thrive there, be worth?

Eight days of oil.

A recent analysis by our team shows that the oil reserves that might be found deep beneath these ancient forest lands could satisfy global oil demands—planes, trains, and automobiles, plastics, AI, and air-conditioning—for a mere eight days. This is the calculus of the oil industry and the profiteers who run it.

At Amazon Frontlines, we have been fighting together with Indigenous communities and environmental and human rights defenders in the Ecuadorian Amazon to seek justice and reparations for oil spills. The recent Esmeraldas spill and the speed with which it caused irreversible damage—to Héctor Pincay’s sight and life, to the farms it has contaminated and ecosystems it has seeped into—is another urgent reminder of the need to link these struggles for accountability and justice to the threats that lie ahead.

We must stop the illegal and forcible expansion of this toxic industry that is destroying the climate, life, culture, and nature, into the last reaches of pristine Amazon rainforest. We can do that by first making sure that oil companies will not be guaranteed impunity for the devastation they will inevitably cause.

Fighting Oil Impunity

On April 7, 2020, as governments across the world were imposing lockdowns to try and control the spread of COVID-19, three oil pipelines collapsed into the Coca River, leading to a nightmare within a nightmare for thousands of Indigenous families in northeastern Ecuador. Just as Ecuadorians were ordered to shelter in place, tens of thousands of people were stripped of their source of water, food, and livelihood. The spill poured more than 650,000 gallons of oil into the Coca and Napo rivers, indirectly affecting some 120,000 people and directly affecting over 27,000, most of them Kichwa Indigenous people.

The accelerated erosion along the banks of the Coca River that led to the collapse of the OCP, Poliducto, and SOTE pipelines was the result of another reckless government investment. In 2010, construction began on the Chinese government-financed Coca Codo Sinclair hydroelectric dam. The dam began operating in 2016, despite protests and numerous environmental impact reports warning erosion would increase downstream of the dam, directly endangering highways, bridges (like this one that collapsed in October 2020), and oil pipelines.

Within a few weeks of the April 7th oil spill, Amazon Frontlines, together with the Interprovincial Federation of the Kichwa Community of the Ecuadorian Amazon, the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of the Ecuadorian Amazon, the vicariates of the dioceses of Sucumbíos and Orellana provinces and some 120 people affected by the oil spill filed suit against the Ecuadorian government, Petroecuador, and OCP, a private pipeline company.

The lawsuit argued that the vast environmental, community, and personal damages of the oil spill could have been avoided. The government ministries, Petroecuador, and OCP were all warned about the instabilities of the region, particularly the increased erosion caused by the Coca Codo Sinclair dam. The collapse of the San Rafael Waterfall in February 2020 due to erosion even led to a series of specific warnings just two months before the spill. And yet, neither the government nor OCP took precautionary measures.

Even after the disaster, neither the government nor the companies took any urgent action, and they failed to provide the affected communities access to water or food, a situation made even worse because of COVID-19. The lawsuit sought immediate emergency relief supplies, such as potable water and food for the impacted communities, long-term clean-up and repairs, and guarantees that measures would be taken to prevent such future disasters.

Four months after it was filed, Judge Jaime Oña Mayorga of the local court in Orellana province called a hearing. The Kichwa Indigenous plaintiffs listened to the Judge through an interpreter as he threw out their lawsuit and denied relief for the impacted communities. There was undoubtedly an oil spill, the judge explained, but the plaintiffs had failed to provide evidence that their rights had been violated by that oil spill.

Our coalition of plaintiffs immediately appealed, and six months later, the Orellana Provincial Court rejected the appeal without listening to the plaintiffs. Then, Judge Jaime Oña went a step further, using the legal system to protect the oil industry over the constitutionally protected rights of Indigenous Peoples and the rights of nature. He filed a retaliatory counter lawsuit against various lawyers representing the victims, including Human Rights Defender and Amazon Frontlines attorney Lina Maria Espinosa and the Kichwa leader Carlos Jipa, accusing them of fomenting “social instability.”

The legal system had gone on the offensive, criminalizing human rights defenders, but our coalition did not back down. We brought our suit before the Constitutional Court, arguing that both the 2020 oil spill and the local and provincial courts’ refusal to address the case constituted systematic rights violations under the constitution.

Over four years after oil spilled into the Coca and Napo rivers—oil that was never recovered by the State or the companies that spilled it—the high court ruled in our favor. In November 2024, Ecuador’s Constitutional Court reprimanded the lower court judges (though not Jaime Oña Mayorga, who had been removed from office for “manifest negligence” in 2022). And it declared that the earlier decisions violated the plaintiffs’ rights to due process, failed to lawfully analyze the central issues of the complaint, and did not allow for true participation of the victims in the judicial process. The suit returned to the provincial court.

Five years after the oil spill Justice Clemente Paz Lara of Orellana Provincial Court called upon the plaintiffs and defendants to reinitiate proceedings and scheduled an intercultural dialogue for June 30, 2025. First the court evaded the Kichwa communities’ request that it be held in their territory. Then, five days before it was set to occur, the court abruptly postponed the dialogue for nearly a month, and set its location outside of Kichwa territory.

After half a decade of demanding justice, this delay won’t stop us. After all, we know Big Oil’s cycle of impunity all too well:

False promises, environmental devastation, community disintegration, sicknesses and deaths, followed by impunity for violations, legacies of contamination, poison, and abandonment of all responsibilities in its wake. Then, they repeat this cycle, often right next door.

Stopping the Southeast Oil Plunder

In 2024, Daniel Noboa, Ecuador’s young, banana-scion president, announced his plans to begin a new round of oil auctions in Indigenous territories deep in the Amazon rainforest. The government wants to drill for oil in fourteen designated “oil blocks” across 8.7 million acres of healthy, intact Amazon rainforest. It’s ready to sacrifice it all for the 8 days of oil that it might find. And while powering the world for 8 days will not enrich the country, it will certainly line the pockets of a few.

To get access to those 8 days’ worth of oil, the government says that it has already complied with Ecuadorian law by consulting with Indigenous communities in those territories in 2012. That sham consultation, however, was proven to be invalid when we worked with the Waorani of Pastaza to win their landmark court victory in 2019.

Now, we are strengthening our movement. On May 13, 2025, a delegation of Indigenous authorities and elders marched to the doorstep of the Constitutional Court in Quito to launch a new round of campaign actions to fight the government’s “Southeast Oil Round”, the euphemism for their illegal plan to auction off Indigenous territories to oil companies and start a new cycle of plunder, poison and impunity.

A Waorani warrior, Wiña Omaca Boyotai, in her late 80s, led over 120 members of her community through Quito while activist and actor Jane Fonda, 87, navigated Los Angeles traffic to arrive at the Ecuadorian consulate. The two elders both delivered the same letter, signed by more than 80 global figures, to representatives of the Ecuadorian government. In the letter, the stakes are clear:

The letter calls on the Constitutional Court justices to carry out hearings in Indigenous territories, as legally required by Ecuador’s principle of interculturality. “We demand hearings in our territory, with Waorani cultural interpreters, so that the judges understand that consultation is not a form to fill out, it is a spiritual pact with the forest and future generations,” says Luis Enqueri, president of the Waorani Organization of Pastaza.

It also calls for the Court to issue a ruling that generates binding, progressive, and novel jurisprudence on the right to consultation and Free, Prior, and Informed Consent and its relationship to the right to self-determination. The justices have an opportunity to declare that the only actors who can decide what happens in ancestral territories are Indigenous Peoples and nationalities.

Creating this progressive jurisprudence based on the Waorani legal victory of 2019 would effectively stop the Southeast Oil Round before it can begin. How? It would require the government to reinitiate the consultation process for Free, Prior, and Informed Consent in Indigenous territories. And the Indigenous communities of the southeastern Amazon have stated clearly and forcefully that they do not want any oil operations in their territories. They want their forests to be healthy, to live and thrive. “Our territory is not for sale and the world already knows it,” says Enqueri. The Court has the power to make sure the Indigenous nations’ decisions are not just heard, but respected.

Yet, we can’t wait on the Court. So, along with our allies, we will keep marching and finding new ways to protect Indigenous rights. Just this month, a delegation of Indigenous leaders was welcomed onto the floor of California’s State Senate, supported by our international campaign allies at the nonprofit Amazon Watch. There, they forced California to reckon with its reliance on oil from the Amazon, making it clear how expanding the oil frontier in the Amazon will cause more devastation and disaster.

While we keep pushing for Ecuador’s Constitutional Court to rule, and for governments to make changes, we have to make sure that the world, as Enqueri says, knows that the Amazon is not for sale. It took five years for our coalition to establish a hearing, which has now been delayed. It has been five years since the Constitutional Court took on the Waorani of Pastaza Case. And in those five years, more oil has been spilled, and more forestlands have been threatened. Just over a week before the publication of this essay, a new spill, predictable and avoidable, occurred again in the same area as the 2020 disaster. In another five years, things will be very different if the Southeastern Oil Auction moves forward or not. We do not want to imagine a world in which it does, because we’ve seen what that looks like.

We know that we can’t go back and stop Texaco’s arrival. We can’t stop the first machine from breaking ground for the Coca Codo Sinclair dam. We can’t warn Héctor Pincay not to wash his face with water from the Esmeraldas river, before his eyes burn and the river turns black. What we can do is continue to demand justice for individuals and communities. What we can do is join together to stop this deadly industry from spreading further into the Amazon rainforest, and from sacrificing so much for so very little.