By Mitch Anderson

One day, a few years ago, Romelia Mendua stood outside of her small house in A’i Cofán Indigenous territory in the northern Amazon with a bag of groceries. Representatives from Petroecuador, Ecuador’s national oil company, had just stopped by with the small care package, after dumping millions of barrels of oil into the Aguarico River. Mendua looked into the bag and saw rice, pasta, and cooking oil; the empty calories of colonization. It was insulting and painful: Many years before, two of Mendua’s small children had died in separate incidents after oil spills.

This is the logic of the oil industry: get the oil out of the ground and on the market at any cost. For those fighting the climate crisis, this cutthroat strategy is compounded by simple geography: the lands that the fossil fuel industry is determined to get to are the same lands that contain the forests, people and cultures that could protect us from the damage the climate crisis has already done.

That same day that Mendua opened the care package, I walked with her husband, Emergildo Criollo, along the river where he usually fished to feed his family. The memory of carrying his dying children weighed on him as he looked at the oily sheen over the surface of the water. We couldn’t see it all but we could feel it; all around us, the razed forestlands, oil fields, pumping stations, pipelines, roads and shanties of the oil industry, encircling the few remaining forests of the A’i Cofán Nation’s ancestral territories.

Today, years later, Ecuador’s government is grappling with debt and economic instability and sees oil as a lifeline. With past loans from China looming, Donald Trump and his oil barons again making decisions in the United States to “drill, baby, drill!”, and global energy markets shifting, officials are eager to secure new oil revenues. So they are gearing up for another round of oil auctions, planning to lease 8.7 million acres of Amazon rainforest to multinational oil companies known for leaving all manner of destruction in their wake.

Oil in the Ecuadorian Amazon

The upper Amazon region just east of the Ecuadorian Andes contains some of the most pristine, biodiverse and vibrant rainforest lands on the planet. Millions of trees there absorb thousands of tons of carbon from the atmosphere every year. It’s home to ten Indigenous Nations and to the Tagaeri and Taromenani peoples, both living in voluntary isolation. The region is bursting with life.

There is also a vast sea of oil under the northern Amazon. The Waorani call this subterranean sea their ancestors’ blood. It, like the forest itself, is sacred to them. When US oil companies first documented these oil reserves in 1964, Criollo was just a boy and his people hunted wild boar along the shores of a vast morete palm swamp. Soon, oil companies began drilling there as part of a wild-west rush to the region. Eventually, the swamp became an oil town called Lago Agrio, named after Texaco’s hometown of Sour Lake, Texas.

As the oil companies extended their operations during the second half of the twentieth century, the Indigenous A’i Cofán, Siona, Siekopai and many Waorani communities were surrounded by new roads, oil fields, and hastily built towns. The Tetete, a small Indigenous nationality living in what is now the Cuyabeno Wildlife Reserve, disappeared completely. The region succumbed to new diseases and high rates of cancer. Wildlife disappeared. Today, the largest oil producing provinces in the country, Sucumbios and Orellana, suffer from endemic poverty and high levels of deforestation. Thick canopies echoing the sounds of the jungle have been replaced by the constant hum of machinery.

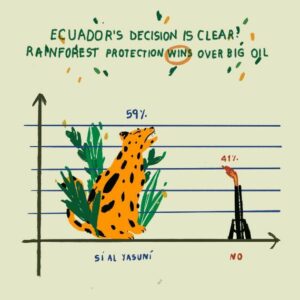

This history is devastating enough but what’s worse is that it hasn’t actually been relegated to the past. Eighteen years ago, the Ecuadorian government asked developed nations to pay Ecuador not to drill for oil in the Amazonian Yasuní National Park. It seemed like it might be the start of a new era but it turns out that the oil industry, nationalized or private, was dead set on further expansion. When other countries failed to pay Ecuador, then President Rafael Correa sent Ecuador’s state oil company into the park, with plans to drill.

In 2012, Ecuador announced an auction of new blocks of pristine Amazon rainforest, across an area of 10 million acres of forests in Yasuní. The announcement set off immediate protests among the Indigenous Peoples who have lived for thousands of years in those 10 million acres. Speaking to a crowd of oil executives, Ecuador’s oil minister focused solely on the oil: He said that anywhere between 300 million and 1.6 billion barrels of it could lie under the area, Indigenous Peoples’ homelands.

But the oil industry wasn’t sold. Indigenous protests spooked the corporate bigs and the government demanded a large portion of revenues. The investment necessary to get crude oil out of the dense rainforest suddenly seemed too high. The auction was unsuccessful. When the government tried to auction the lands again in 2018, Indigenous people once again took to the streets. And this time, they also went to the courts.

Ecuador prepares to launch a new oil round

In 2012, the Correa government claimed they had complied with Ecuadorian and international law by carrying out a series of consultations in the Indigenous territories they were putting up for auction. The government said it had fulfilled the requirements of “free, prior and informed consultation” among the Waorani people of Pastaza province, in order to drill and extract oil from these territories, which they called Block 22.

What they actually did was fly into Indigenous communities unannounced, hand out bread and sodas, ask people if they wanted a new school and then invite them to sign attendance sheets. They then used those signatures as proof that the government had consulted the Indigenous communities. People who signed their names that day heard nothing about their homes being leased to the highest bidder.

Nemonte Nenquimo, then leader of the Waorani Organization of Pastaza, along with four Waorani elders–Memo, Wiña, Omanka and Dika–and the legal team of the non-profit Amazon Frontlines, sued the government. In 2019, after years of legal battle, they won a landmark victory which invalidated the 2012 “consultation” and effectively stopped the massive oil auction in its tracks.

Since then, Ecuador’s Constitutional Court has had the 2019 victory on its docket, in order to enshrine the right to “free, prior and informed” consent into Ecuador’s constitution. When it rules, the Court can establish parameters for seeking consent.That could include features like carrying out assemblies in territories with proper prior notice, in Indigenous languages, and according to local practices. Flying in unannounced, under false motives with sign-in sheets wouldn’t work anymore. But the Court has not set this jurisprudence, which means that, despite their legal victory, Indigenous People’s rights remain at the whim of governments and the oil industry that care more about profit than life itself.

The current president of Ecuador, the banana scion Daniel Noboa, knows this. Ecuador recently announced its plan to initiate another “oil round,” the official euphemism for plotting the mass destruction of the Amazon rainforest and the Indigenous People who call it home. The government wants to drill for oil in fourteen designated “oil blocks” across 8.7 million acres of healthy, intact Amazon rainforest. Official documents describing these plans say that all the Indigenous communities in the area have already been consulted. Their proof? It’s the 2012 sham consultation that was legally invalidated in 2019.

Ecuador’s government knows their proof is unsound so, unlike in 2012, when Rafael Correa announced the oil round in the Amazon with bravado in Quito, Ecuador’s capital, this time officials are quietly trying to make bi-lateral deals on the fourteen “oil blocks.” These backdoor deals have a dual purpose: they make it harder for Indigenous Peoples to protest and they help to mislead the oil companies themselves. Drilling for oil deep in the dense, roadless Amazon rainforest requires major investment from these multinational corporations. The Ecuadorian government wants to convince them that those investments will be safe and profitable, unopposed by Indigenous Peoples. They won’t.

The Indigenous Peoples of Ecuador’s south-central Amazon are already organizing to derail this oil auction. Many of the region’s largest Indigenous organizations, including the Confederation of Indigenous Nations of the Amazon (CONFENIAE) as well as the regional federations of the Waorani (OWAP), Sapara, Achuar, Andoa, Shiwiar, Shuar (FENASH) and Kichwa (Sarayaku and PAKKIRU) have legal strategies and social protest plans prepared for whenever the auction officially goes public this year.

The Waorani people’s victorious 2019 lawsuit is the tip of a legal spear–both at the Constitutional Court and at local courts to stop this oil auction. Many Indigenous nations and international legal scholars are already submitting amici curiae (“friend of the court” letters) to the Court, encouraging the justices to enshrine free, prior and informed consent into nationally binding jurisprudence. The Court has an obligation to establish legal requirements for future consultations with true Indigenous participation in Indigenous territories, nationwide. If they fulfill this obligation, then each Indigenous nation would have to give their consent before any company or state actor could enter and exploit their territories. It would stop the oil auction in its tracks.

But even without waiting for that ruling, the 2019 victory is already in hand, and waves of new lawsuits by the Indigenous nations affected by the upcoming oil round will be filed at the provincial levels, jamming the auction up in the courts before it can even get started. This should—and will—raise corporate alarm around the world.

Indigenous Peoples in the Amazon have powerful international allies that will shine a spotlight on the Ecuadorian government. And if the current president, Daniel Noboa, remains in power after Ecuador’s ongoing elections, this will be an important year for him to polish his environmental credentials at COP30 in Brazil. As a candidate in 2023, Noboa famously opposed drilling for oil in Yasuní and promised that, if elected, he would respect the national referendum against it. Launching a new oil round in the Amazon which faces unified Indigenous opposition is not a good look for the press-obsessed leader.

Indigenous resistance on the frontlines of the climate crisis

Last year was the hottest in recorded history. The last decade was as well. And it’s not just the heat; in the last few years, climate change-fueled fires have destroyed millions of acres in the Amazon and entire neighborhoods in Redding, Paradise and Los Angeles.

As Amazon Frontlines recently explored in The Tipping Point: Is the Amazon Rainforest approaching a Point of No Return?, scientists estimate that the deforestation of between 20% and 25% of the Amazon could trigger a tipping point and endanger the survival of the entire region. It could transform the world’s largest rainforest into billions of tons of carbon dioxide lodged in the atmosphere and further accelerate global warming. We are poised on the edge of a very steep fall.

And the reason is simple: we’re the ones who continue to light the fires (and incite other extreme weather disasters) with our planes and cars, our smartphones and Amazon Prime deliveries. In November 2024, global fossil fuel emissions were on track to beat the previous year’s record high. Then, on January 20, 2025, Donald Trump signed executive orders withdrawing the United States from the Paris Climate Accords, defunding alternative forms of energy, freezing federal funding for programs to address climate change and promising, once again, to “drill, baby, drill.”

We are stuck in a truly vicious cycle:

We’re addicted to our way of life in our industrial societies, which are addicted to oil, pushing regional governments and multinational companies to reach into the most remote regions of the Amazon rainforest to extract the last drops of it, because it fuels their own addiction to profit. And it feels like there is nothing we can do to stop it.

But this year, in Ecuador, the world can take a step to break this cycle, by drawing a line and cutting corporations and governments off from the source of their profits. And Indigenous Peoples are leading the way.

We have to support Indigenous Peoples battle by battle as they make it clear to the Ecuadorian government and any corporation that wants to enter their territories for oil that their company’s bottom line will not be guaranteed, that their shareholders will not feel secure, that the land cannot truly be sold. And we’ll have to do this more than once, all over the Amazon: This year, there are more oil and mining concessions slated for Perú and Colombia that could have devastating impacts on more than 18 million acres of pristine forests.

But we can start here, in Ecuador, where Romelia and Emergildo still dream of their children, before the oil companies came, and where they stand strong protecting their territory for all those yet to be born there. We can help Indigenous Peoples to draw a line in the sand, to leave two spears crossed on the global oil industry’s trail: do not cross this line; do not “drill, baby, drill” in the heart of the Amazon rainforest; no more oil and mining in the Amazon, no more memories of dead children, no more disappeared cultures, no more fish floating belly up in the oil-slick rivers, no more rainforests scorched into savannas.

We have to draw a line not only because we fear the end of the world but because we know that the end of this world, the one addicted to oil, is possible. And we have to do it now.