For decades, the legendary Siekopai elder and healer Don Cesáreo Piaguaje had a clear vision: recovering the ancestral homeland of his people.

Over eighty years ago, as war broke out between Peru and Ecuador, the Siekopai people were forcibly displaced by militaries from their spiritual heartland known as Pë’këya (Lagartococha). Many Siekopai families tried to return, only to be met with abuse and detention by military authorities. Despite the setbacks, Cesáreo always insisted on dreaming of his people returning to their territory.

In the first days of April 2023, Cesáreo left this world. Just seven months later, on November 24th 2023, a northern court in the Ecuadorian Amazon delivered a historic verdict, ruling that the Ecuadorian government must return the ancestral territory of Pë’këya to the Siekopai nation, formally recognising it as theirs.

The verdict brought an outpouring of emotion, and a reaffirmed recognition of the leadership and vision of Cesáreo. His prophetic dream came true, leaving a legacy that opens a new chapter in Siekopai history, and lays down a landmark precedent that empowers Indigenous communities seeking to title and recover their lands from government hands.

In the wake of Cesáreo’s departure and the fulfillment of his prophecy, we share with you a heartfelt tribute, written by Luke Weiss, a long time friend of Cesáreo’s, and the coordinator of Amazon Frontlines’ Cultural Recovery and Territorial Mapping programs.

Tribute to Don Cesáreo Piaguaje

Photo: NAISEPAI.

On the afternoon of April 5th 2023 in the Ecuadorian Amazon, the great elder and yagé ukukë (shaman) Don Cesáreo Piaguaje departed from this world. According to him, he was now embarking on a red canoe that would carry him on his journey along the river Ume Tsiaya in the eternal realm.

I want to take a moment to honor the sacred memory and teachings of this Siekopai spiritual leader with you. My name is Luke Weiss, and I spent over a decade living next to Cesáreo’s home, learning from his incredible knowledge of the forest, Siekopai tradition, and ritual healing techniques.

I want to tell you, in a few words, why Cesáreo was such an exceptional person, and why he was so dear to his people.

Don Cesáreo during a canoe journey towards Pë’këya on the Ecuador-Peru border.

“Just how old is Don Cesáreo? 107? 127? 197?” This question was so frequently asked by those of us who had the honor and fortune to know Cesáreo Piaguaje or Kāmpora’sa as he was named among the Secoya (Siekopai) people. A curiosity arisen not so much from his advanced age– but rather from hearing his inexhaustible archive of stories of adventures in the rainforest, including escaping gunfire during World War II, wreaking vengeance upon abusive rubber barons, and trading jaguar pelts for his first muzzleloader. Or from hearing his unparalleled knowledge and understanding of the rainforest, his entire mental encyclopedias of the natural and spiritual worlds.

His knowledge of the rainforest involved an intricate awareness of mammals, birds, insects and reptiles. Not just knowing their names, but also which “clan” particular animals belong to. He knew their characters, behaviors, diets and preferences; how a specific insect pheromone for enticing specific fish species into a feeding frenzy; how a particular hollow bird bone is used as a love charm, or which bird feather is best for perfecting the shine in the barrel of a blowgun; which lizard skin can be applied to pull out deep splinters; which tree seed can be prepared as a purgative to cure tuberculosis; which monkey provides the ideal drum skin, or even how to track a wasp to its hive. “How long must one live to learn all of this?!”

Painting depicting the spiritual realms of Pë’këya by Cesário’s son, César Piaguaje.

Cesáreo embodied the fearless master of his forest world. A skilled and prolific hunter, fisherman, and master craftsman of dug-out boats, paddles, hammocks. Cesáreo was also a brave leader, who guided his people during historical relocations, and led his people to return to the ancestral heartlands of Pë’këya – a place he referred to as the savior lands of his people.

Photo: Courtesy of Pablo Yépez.

He was also a creative artist, always perfecting the art of crown making, beadware, and face painting. His meticulous detail when describing the “proper” intricacies of house construction, the butchering and smoking of a tapir, or even the delicate removal of larvae from deadly wasp hives for fish bait, would carry on for hours, and elicit language rarely spoken in modern days.

In his physical prime, which began earlier and lasted longer than most, he would acquire near-legendary acclaim for his ox-like strength. This he flaunted doing practical things like building homes of absurd size featuring inconceivably massive timbers in the post and beam architecture. “How did he get carry those posts all by himself?” Or arriving home with a massive leaf-woven backpack of wild meats: “How did he carry this so far and over all those hills? He was also the first Siekopai member of the Ecuadorian military and was given the nickname “jai sodao” or big soldier, attributed to his size and strength. “How did he get so strong”? Perhaps one of the many phrases he used daily to motivate those around him such as “dale no mas, sin miedo” (just go ahead, without fear), is a clue to the inner sources of his marvelous feats.

Left: Cesáreo, Basilio and Javier with an ancestral ceramic artefact found during the archaelogical investigations led by the Siekopai Nation in Pë’këya. Photo: Courtesy of Manuel Pallares. Right: Don Cesáreo Piaguaje stands alongside an airplane owned by evangelical missionaries. Photos from the 1990s by the Summer Institute of Linguistics (ILV)

Yet even Cesáreo’s legendary strength and feats were preceded by his reputation as a healer. For Cesáreo was also a shaman: a rare status granted to those with the ability to intermediate between the material and immaterial worlds. Through a decades-long apprenticeship with grandparents, uncles, and cousins, wherein he consumed countless pots of brewed plants, primarily yagé or ayahuasca, and also yoco, peji, ujajai, and mañapë (plants virtually unknown to the western world) he learned to summon spirits to envelop his body and soul and endow to him the ability to heal through a bundle of leaves, his bare hands, or his mouth.

During his life he would heal thousands of people, working to cure everything from poisonous bites to infertility to mental illnesses.

Whether complete strangers or a close family member, he would attend the ailments with the same selfless sacrifice and concentration. But he could just as well use his candid, jester-like nature to just speak frankly to people, and never restrained from giving straightforward advice.

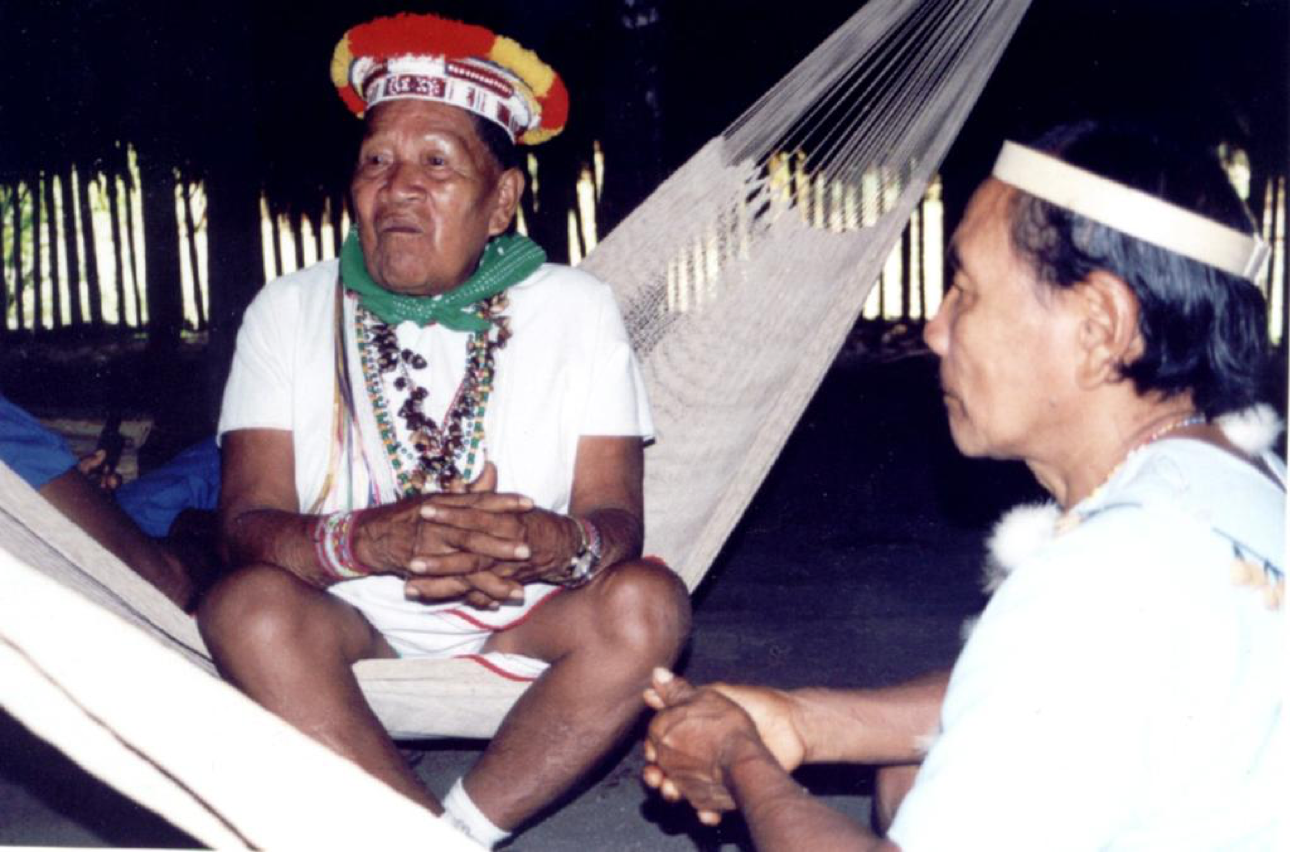

Don Cesáreo rests in a hammock during a visit to Wajoya, as part of a community mapping process aimed at recovering their ancestral land on both sides of the border.

Cesáreo’s role as shaman went far beyond healing, he was also responsible for and adept at maintaining balance and well-being of his people. For Cesáreo, dreams and visions were not one-directional, like watching television, but rather spaces to interact with – a portal to the strings of the universe and opportunities to prevent calamity, avoid danger, and bring plentitude to his people. In the late 1990s, he spent many months chanting and singing in his hammock, weaving a spiritual veil to conceal the oil in a remote and pristine region of his territory from the greedy eyes and seismometers of the oil company. During times of scarcity, his communication with the spiritual world was focused on summoning packs of wild peccary, or with mythical fresh-water whales to trigger fish migrations in the lower amazon basin. But perhaps Cesáreo’s most important life-long spiritual engagement was to ensure that the ancestral lands of Lagartococha were once again the homeland of the Siekopai people.

Cesáreo lived his last decades fighting for his community’s right to return to the Siekopai’s ancestral homeland of Pë’këya, where they were displaced from. He spent decades sharing stories, passing on knowledge to younger generations, and encouraging communities to protect their ancestral culture. Elders are libraries of memory for communities, and each passing emphasizes even more the urgency of protecting collective knowledge.

Siekopai community members work on a collective artwork in tribute to Cesáreo Piaguaje shortly after his passing in April 2023.

So just how old was Cesáreo? That question, and many other fascinating peculiarities about the man will never be known. But fortunately, he left behind more answers than questions. Answers to how to live life courageously, how to thrive in extreme conditions, how to feel a part of something bigger out there through being selfless, and how to just laugh.

Watch this tribute to the Great Shaman, Don Cesáreo Piaguaje

In his later years, which westerners might interpret as a sort of dementia, Cesáreo would suddenly change whatever topic of discussion was going on and warn those around him of an imminent flood, almost of biblical proportions. He warned that what we see today as the Aguarico and Napo rivers will bring flood waters, leaving no dry land in the areas where people live today. The only salvation for the Siekopai people in his eyes were the high forests near Cuiña jaira or the Piudi lagoon, named after a relative of the endangered curassow bird that has recently gone extinct in Ecuador. That was where he dreamed for his people to create a village, and a yagé house to maintain the Siekopai way of life.

Perhaps Cesáreo’s vision of floods was his way of interpreting the western cultural assimilation he saw taking over his people, a mixture of unhealthy foods, strange addictions to little technological devices, and a disconnect from the spiritual world.

As he departed from this world, just months later, his prophetic dream of the Siekopai nation recovering their ancestral homeland was fulfilled. Time will tell us about his prophecies of warning.