By Luisana Aguilar / Illustration: Erick Retana

What is a basket? It could just be an object that makes it easier to carry things, but for the hands that fold, intertwine and weave the leaves, for those who traveled the forest looking for the material, a basket is an item that carries with it knowledge transmitted by their ancestors. It is a practice vital for day to day life.

As Emeregildo Criollo, a Cofán grandfather, narrates, “My grandmother was my teacher, she taught me how to weave baskets. With her I learned where I can get materials, what size they need to be, and how many strips I have to cut for the size of basket I have to make.”

Without intending to, Emeregildo’s grandmother taught him mathematics, geometry, botany, geography, art and more, because, like the basket, knowledge is intertwined and woven to form a firm, flexible, beautiful and useful structure for life.

So, is it possible to teach Western subjects from the formal education system through the lens of ancestral knowledge? The answer to that question has been developing since 2019, when communities of three Indigenous nations from the Ecuadorian Amazon – A’i Cofán, Waorani and Siekopai – with the support of Amazon Frontlines and Alianza Ceibo, began a path of reflection, discovery and creation of their own model of education linking ancestral knowledge with Western learning. These models aim to be contextualized to their realities and taught within their territory.

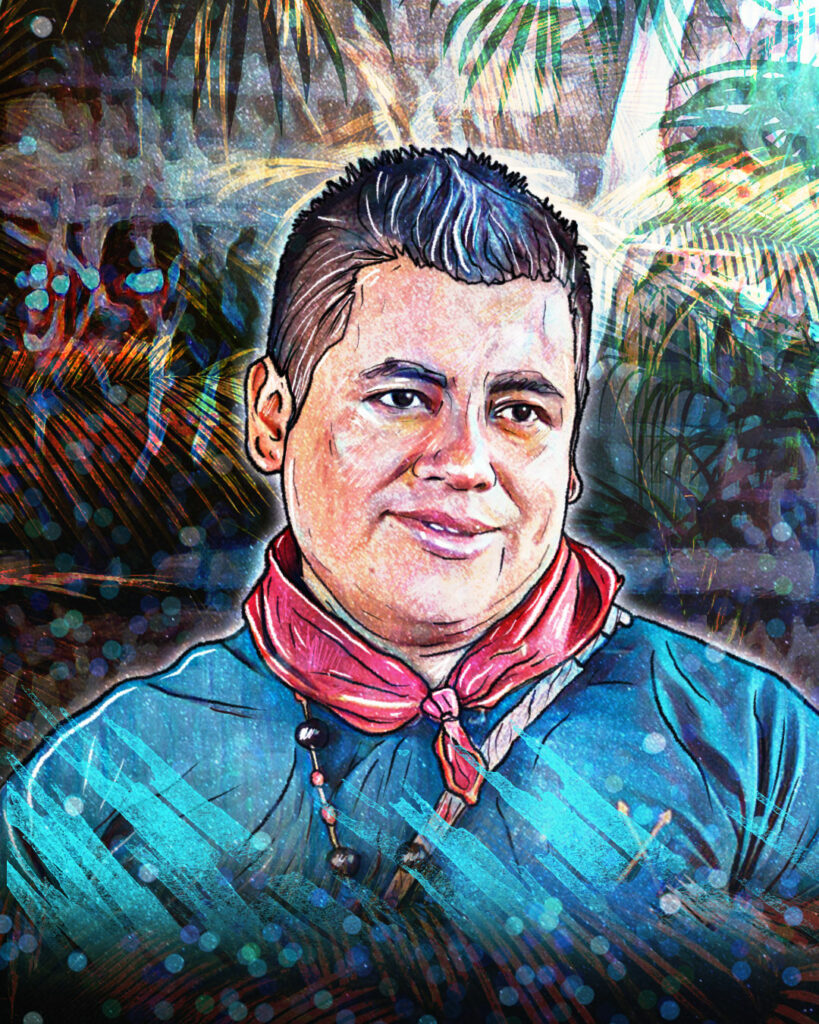

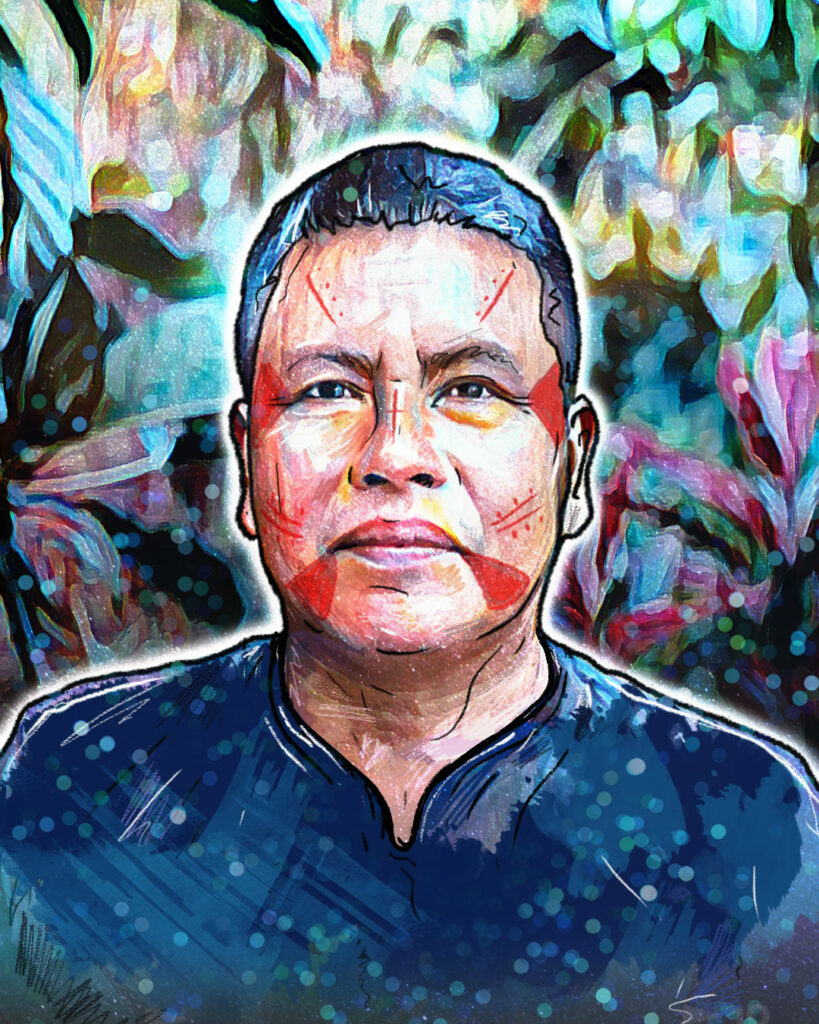

In this special, we listen to six Indigenous leaders across the three nations as they share their experiences, reflections and dreams on the path of developing their own education systems. They are Emeregildo Criollo and Wider Guaramag of the A’i Cofán Nation, Wilmer and Justino Piaguaje of the Siekopai Nation, and Gaba Guiquita and Nemonte Nenquimo of the Waorani Nation.

The Experience of a Colonial Education

Nemonte Nenquimo and Gaba Guiquita were afraid of how the Cowori (people from outside) teachers would punish them when they did not understand the lesson taught in Spanish in the little school in their Waorani community of Pastaza in the north-central Ecuadorian Amazon.

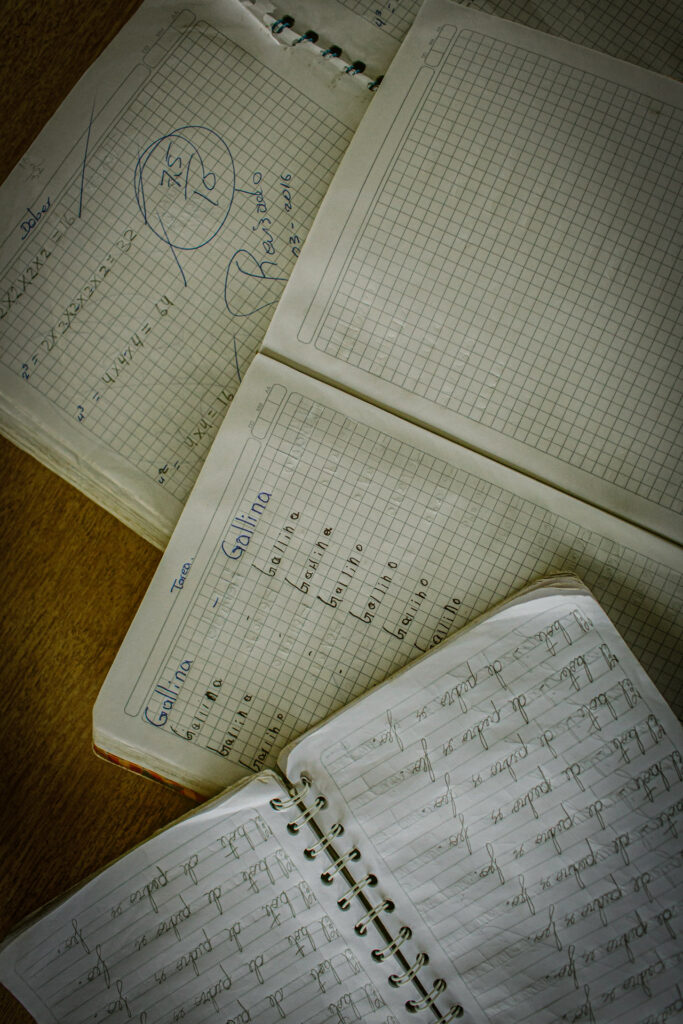

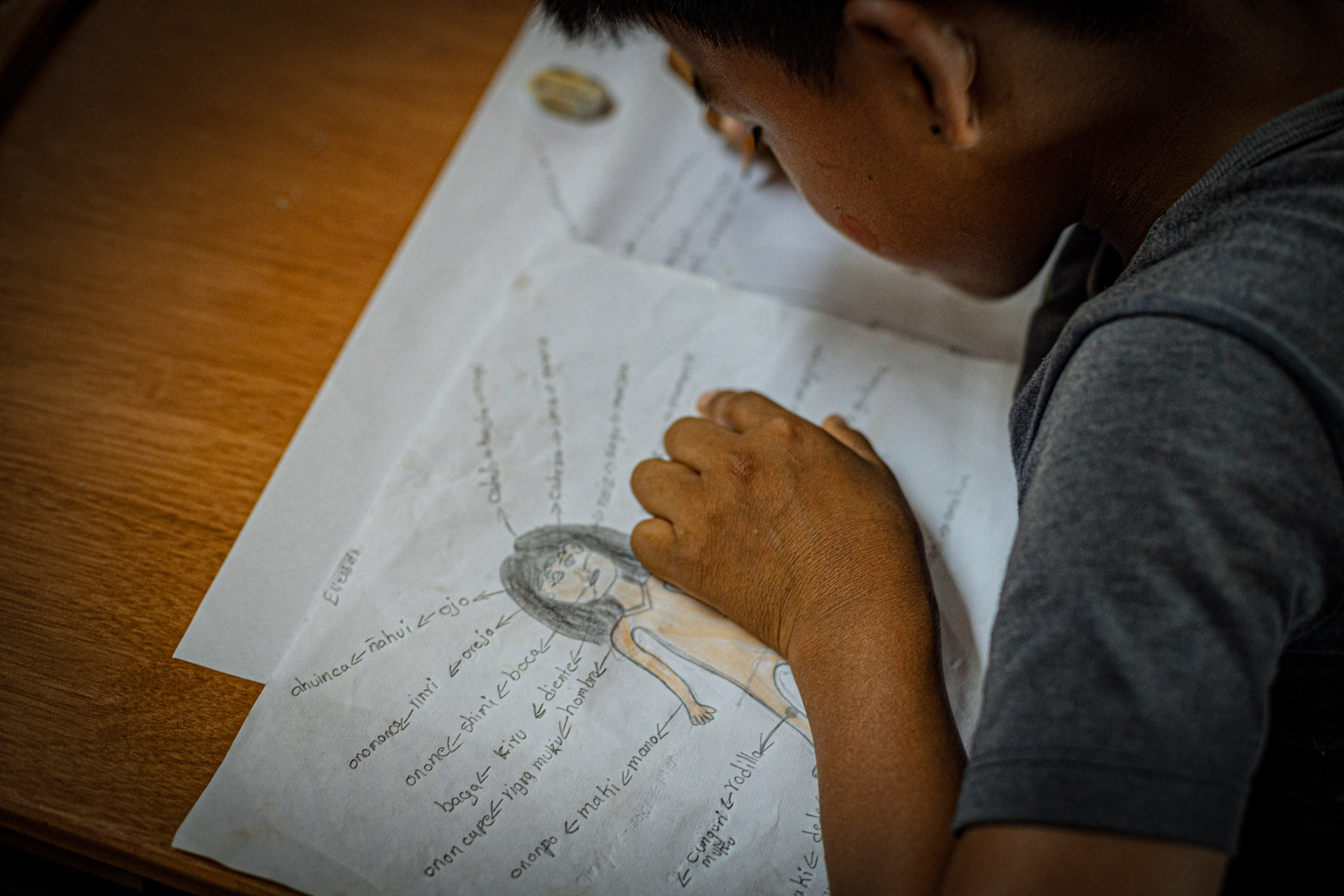

Nemonte narrates that these teachers “came from Puyo and Ambato (cities 75 and 138 km away, respectively), they spoke Spanish, and when I was six years old, I didn’t understand the Spanish language that well. Speaking, writing, and reading were very difficult for me.” And she asked herself, “Why couldn’t they teach me in my language, Wao Tededo?”

Justino Piaguaje and Wilmer Piaguaje attended primary school in their Siekopai communities, but to advance in their studies they had to leave their home and community, traveling by river and road to study at a boarding school where classes were taught in Spanish, Kichwa and English – but their language, Paaikoka, was not part of the curriculum.

Emeregildo Criollo of the A’i Cofán nationality was educated in 1973 at the Summer Linguistics Institute – ILV – in the community of Dureno on the banks of the Aguarico River, where the consumption of their sacred plants Yocó and Yagé was prohibited because they were considered ‘satanic.’ Emeregildo says that even now some people in the community attend church and refuse to drink the sacred drinks that allow them to connect with the spirits of the jungle.

These leaders share common experiences of a colonialist education brought by religious institutions such as the evangelical Summer Linguistic Institute (ILV), which was present in Ecuador from 1953 to 1981. Catholic missions also participated, and their presence in the Amazon dates back to 1700, one of those missions being the Capuchins. Finally, there is the State educational platform promoted through community schools and boarding schools.

The focus of this education was functional: knowing how to read, write, and add; but also to evangelize, which implied annulling Indigenous spirituality to make way for Judeo-Christian spirituality. For the State, the purpose of schooling was the assimilation of Indigenous culture and its integration into the dominant culture (Oviedo, 2017).

Despite evangelization, cultural clashes and abuse, these Indigenous leaders recognize that the education they received allowed them to communicate with the outside world, learn about other cultures in addition to their own, and subsequently, confront mining, oil, and agroindustrial extractivist threats, and defend their territory. But they are adamant that conditions and processes must change.

For example, for Nemonte Nenquimo, it is essential that the education model moves from one where students stay in a classroom “shouting out letters” to one in which students feel free. Wider Guramag, president of the A’i Cofán community of Sinangoe, is concerned that Indigenous youth, when leaving the communities to continue their studies, lose their community values, their practices, their language – which is why it is essential that community-led education protects the culture.

“It is essential to strengthen our own worldview and, at the same time, continue with scientific knowledge. From basic education through upper schooling, we can strengthen culture; in this way, when [young people] must leave, there is no longer a risk that learnings from abroad will weaken what we have protected here in the community.”

From Reflection to Action

Bilingual Intercultural Education (EBI) was institutionalized in Ecuador in 1989 for the schooling of Indigenous peoples, and within that framework, the Bilingual Intercultural System Model – MOSEIB was established in 1993, which establishes the policies, principles, and objectives of the EIB. This model was built with the participation of Indigenous actors who had been fighting for education in their own languages and worldviews, but who lost their direction on the path to institutionalization.

According to the study by Alexis Oviedo – Bilingual Intercultural Education in Ecuador (1989-2007): Voices – the EIB and the MOSEIB were important achievements of the Indigenous movement, but their objectives of constructing curricula adapted for each Indigenous people and nation were not achieved. These processes have also been questioned for having an Andean-centric conception, to the detriment of other worldviews such as the Amazonian ones.

The MOSEIB was a subject that Wilmer and Justino studied in their final years at boarding school, where they trained as teachers. The framework was also Gaba’s guide when he was hired as a teacher in his community, without having much knowledge. And it offered people an opportunity to do things a little differently, as Wilmer explains:

“[The MOSEIB] was a pretty good orientation for the community, because once completed, we had to teach the children. They gave me this opportunity to be a teacher and it was already another way of teaching, not like my first teacher who taught shouting with a ruler. We said, that’s enough! We came in with the ideas of singing, playing. The young people who finished their high school, with what I taught and the little I could, now thank me for having learned more than with other teachers – to read, write and understand the community organization, our rules. Some of them are now leaders themselves.”

These experiences have been key in shaping the initial reflections of community-led education processes. However, the path toward development has resembled the rainforest itself: without straight lines, wrought with obstacles, and so much to observe and analyze. As a result, the initial objectives of the Indigenous leaders promoting community-led education have changed significantly since they started to where they are now.

Patricia Peñaherrera, an Amazon Frontlines technician specializing in community-led education, remembers that at the beginning of this process, the main concerns of those working on education proposals were to develop pedagogical models for Indigenous youth to learn Western subjects. Together, people sought efficient ways to implement the MOSEIB. Now, community-led education is considered a more suitable way to recover ancestral memories, cultural practices and pedagogy.

As part of the road already taken, the three nations have already carried out diagnoses in 16 communities to understand the state of education in each one and take appropriate action. One of the common problems identified is the separation of the family and community circle in the education of boys and girls, which is why the involvement of the entire community has been seen as essential to the process: fathers and mothers, teachers, wise elders or Pikenani, political and spiritual authorities, and the Indigenous guard.

Other common problems are the lack of teachers from the Indigenous nation itself, an absence of training, loss of language and culture among young people, as well as a lack of access to education, and other problems related to the Ecuadorian State.

A key observation in the diagnoses was the situation of the A’i Cofán community of Sinangoe, where 75% of young people between 17 and 25 years old do not study, while 73% have the desire to continue their studies to help their family and community. However, the monetary cost involved in leaving the community to access secondary, high school and third-level education is one of the main reasons for dropping out of school. Another challenge facing the community is the lack of educational infrastructure.

In the Siekopai Nation, a disarticulation was found between teaching and the Paaikoka language, as well as between the educational curriculum and the ethnographic context. In the Waorani communities, around 76 different problems were distinguished, most notably the lack of teacher training and relevance of the curriculum to Waorani cultural practices.

Departing from these problems, the three nations have set their priorities. Although each process continues at its own pace, their parallel paths feed off each other and share mutual inspiration.

Through the process of curricular framework development, the Siekopai nation has initiated projects such as the reworking of extensive documentation of Siekopai history written by anthropologists, priests and scientists, now combined with the information provided by grandfathers and grandmothers to tell their story in their own voice. One shared communal goal is to publish the treasured memory in a virtual library so that communities can access this information in the future. They are also developing a Paaikoka dictionary.

In the community of Sinangoe, the self-education process of the A’i Cofán nation is being developed. As part of the curricular framework, they are building a guard training base, where boys and girls can learn about land defense from an early age, inspired by the Indigenous guards in their community. They have also held monthly workshops for cultural revitalization, where for example elders from the community have taught children and young people how to make clay pots and weave nets for fishing.

The Waorani nation has worked on the implementation of pilot projects in the communities of Daipare, Obepare, Nemonpare and Kenaweno, improving educational centers and building new classrooms with differentiated spaces and teaching materials. They have also elaborated an educational proposal that includes the community and wider participation of the Pikenani, especially in learning about plants through agro-ecological gardens and walks through the rainforest.

Like threads, these processes of self-education, although intertwined and interwoven, are each unique, yet all working toward the protection of the most important forest and water system on the planet.

Relationship with the State

Since 2019, when the Amazonian Indigenous A’i Cofán, Siekopai and Waorani nations began to develop their own educational systems, they knew they were facing a common challenge: the relationship with the State and its educational platform for Indigenous peoples.

Despite the institutionalization of Intercultural Bilingual Education – EIB – in 1989 and the efforts to guarantee the right to education for Indigenous children and youth, they still struggle with lack of access to education (especially post-primary school), precarious educational facilities, scarce pedagogical material, insufficient and unprepared teaching staff, and a rigid and inefficient bureaucratic system, according to the testimonies of those developing community-led education.

Since 2020, the Waorani Organization of Pastaza has advocated for the Ministry of Education to provide funds to hire Waorani teachers and for them to be adequately trained and evaluated, considering not only MOSEIB guidelines, but also ancestral knowledge and territorial context.

Nemonte Nenquimo expresses how challenging it is to implement new ways of educating when “Waorani teachers have only been trained with the system of the Ministry of Education. They do not have our cultural context, only the culture of the Ecuadorian State, translated for the other nationalities. They have gotten used to working that way.”

A similar situation has occurred in A’i Cofán and Siekopai communities. Yet when communities have developed their own training spaces for educators, they have not been able to obtain permission from the Ministry to operate.

Emeregildo Criollo shares, “We went to Sinangoe to work with the teachers, but they said that without authorization from the Ministry of Education, they could not participate in the workshop we had developed to teach the children. After that, we requested authorization from the Ministry to allow the teachers to participate in the workshops, but we didn’t receive a response. If the teachers abandon their classrooms to go three, four, or five days to train, they will be fined, because it isn’t authorized by the Ministry.”

The leaders of the nations have made the first approaches to the Ministry to demand that the conditions of education change and to obtain approval for the curricular framework they have developed. Without this approval, it will be difficult to implement it in community classrooms.

Meanwhile, other demands are being made. For example, the A’i Cofán community of Sinangoe hasn’t had educational infrastructure since 2018, when the one they had was disabled by a natural process of regressive erosion of the Cofán River, on whose bank they are settled.

Since then, the community leadership has dealt with long delays, waiting on the construction of a new school. They have instead opted to build their own classroom with the support of Amazon Frontlines and Alianza Ceibo.

Despite the obstacles of the state, the work within communities has not stopped. They have worked hard to involve the entire community in the formal and cultural education of girls and boys.

Community-led Education to Generate Autonomy and Defend the Territory

In the hearts and minds of those fighting for community-led education are all the future generations, and a strong desire to ensure intellectual, cultural and spiritual growth. There is the ancestral knowledge of their elders: living libraries that are dying out. There is also the relationship with the territory, how to care for it and respect it so that it can sustain the global climate.

The rainforest in itself is a school, and fathers, mothers, grandfathers and grandmothers are full-time teachers who guide their children in survival and territorial care – things that are not learned in a formal education classroom.

The defense of the Indigenous territories of the Amazon is closely related to the care and conservation of the largest rainforest in the world. Cultural protection means, among other things, that future generations will not fall for the deceptions of corporations.

Community-led education is a challenge to what has already been established – it seeks to create autonomy and decolonize conservation models. It does not see education as simply a pipeline toward joining the labor ranks, but rather aims to question Western ways of life which are actively leading the planet to its own extinction, and are trying to be instilled in the communities.

The call to the world is to do Minga (community work with a common purpose) and support Indigenous peoples in achieving their autonomy. Science has shown that forests in the care of Indigenous peoples are the most carefully conserved, and community-led education ensures that this care can be maintained in time.

Community-led education is like that basket woven with leaves gathered by foot and braided by hand, with strong effort, without predation or waste. A basket that allows us to carry everything that is important with us: knowledge, science, culture, and territory.

These are the words of Gaba Guiquita, from the Waorani community, who best describes it: “The first path is the territory. Without territory, community-led education cannot function. There must be healthy forests, healthy waterfalls, the songs of the Pikenani, the ways of living of Pikenani, the ways of living of young people, of children.”