Many Indigenous peoples can identify their heartland: an area so critical to their physical and cultural livelihood that without it, their existence is imminently threatened. For the Siekopai (Secoya), a nation at risk of cultural and physical extinction, this ancestral heartland is Pëkëya or Lagarto Cocha, a hypnotic labyrinth of blackwater lagoons and flooded forests on the border between the Amazon rainforest of Ecuador and Peru.

Among Amazon river dolphins, caimans, and a multitude of birds whose colorful plumage rivals with the multicolored tunics of the Siekopai, over 200 community members traveled by canoe to Pëkëya last month for the nation’s second bi-national gathering. It couldn’t have been any timelier. This small transborder nation, which numbers just 800 on the Ecuadorian side and 1,200 in Peru, is waging legal battles that could determine the survival of their culture and people – and set precedent for many Amazonian Indigenous communities seeking to regain control of their ancestral territories. In both countries, the Siekopai Nation has launched strategic litigation to take back over half a million acres of their ancestral lands from State hands, while at the same time overturning outdated laws and breaking down administrative barriers to guarantee true Indigenous ownership of tens of millions of acres of Amazonian territories.

In this photo-essay, we share a window into the Siekopai’s gathering and we hear from Siekopai youth, elders, and leaders themselves on why their future depends upon getting their land back.

“Pëkëya” is the name of the ancestral heartland of the Siekopai people in their native language, Paicoca and is located along the Lagartococha River. The Peru-Ecuador war between 1941 and 1998 forced the Siekopai out of Pëkëya.

Siekopai families from the Ecuadorian side travel 10 hours by canoe to reach Pëkëya. Most Siekopai families were displaced some 160 kilometers (99 miles) west of their homeland, in the rural settlement of San Pablo de Kantesiya, a community located along the Aguarico river, surrounded by oil and African palm oil and rapidly spreading colonization and deforestation.

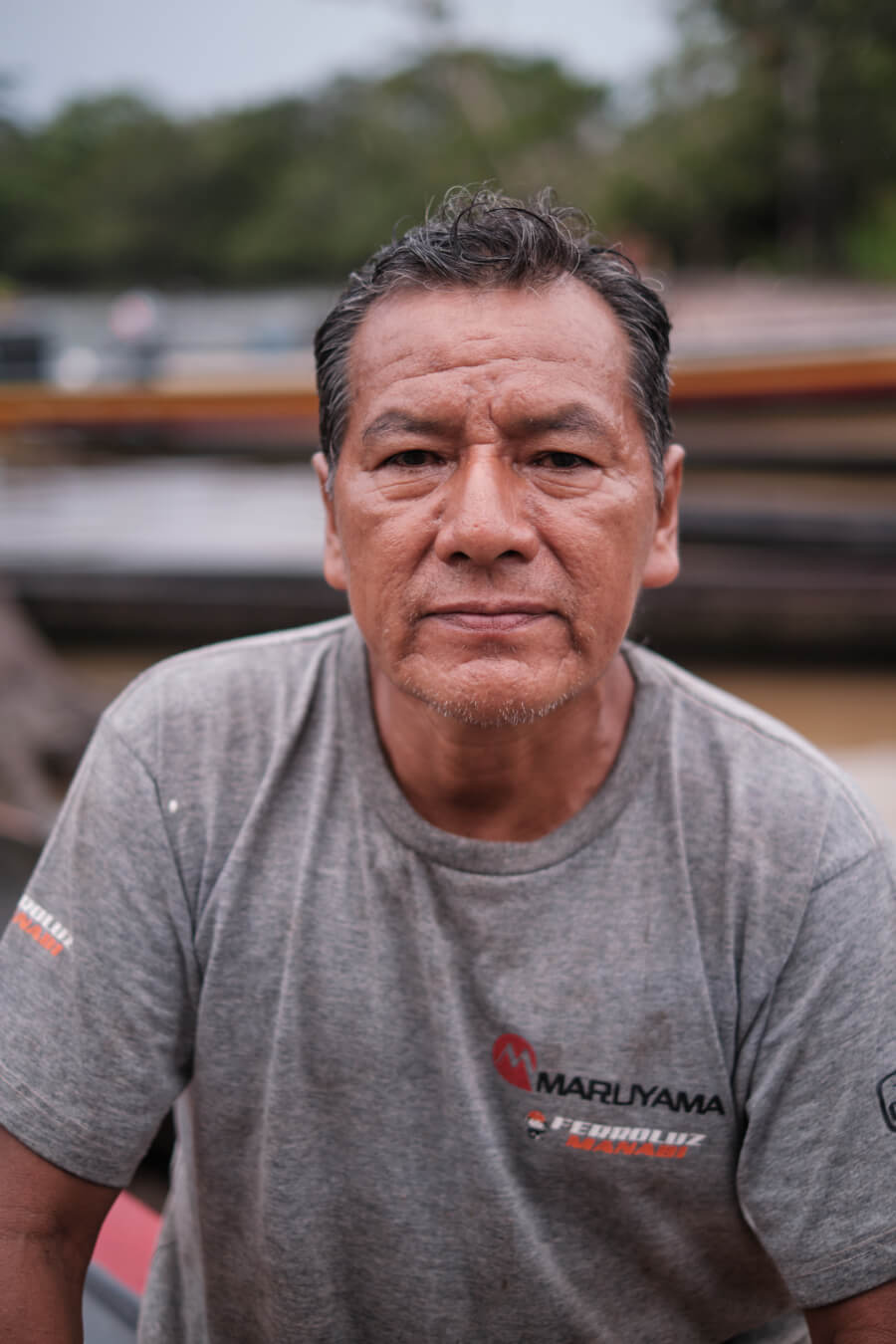

Siekopai community members attending the bi-national gathering in Manoko.

The Siekopai’s ancestral territory once stretched some 7.4 million acres between the Putumayo and Napo rivers from Ecuador into Colombia and Peru. In Ecuador, the Siekopai currently have no legal title or recognized rights over their ancestral territory and have been corralled into a much-reduced territory of 50,000 acres.

Siekopai women adorn themselves with plant-based paints and designs inspired by animals of the Amazon rainforest, such as anacondas and jaguars.

Siekopai community members from the Ecuadorian side of the border prepare to reunite with their relatives. State-imposed borders and war separated many families for as much as five decades.

Over 200 Siekopai people gathered in the village of Manoko on the Peruvian side of the border in Pëkëya to strengthen the cultural and spiritual bonds of a new generation that, due to the decades-long war in the region, must now rediscover Pëkëya.

Siekopai women wash clothes in the village of Manoko.

Pëkëya lies in the heart of a vast protected area — the Cuyabeno Wildlife Reserve — it was designated in 1979 by the Ecuadorian government, without the consent or consideration of its ancestral stewards.

During the gathering, the Siekopai visited numerous sacred sites including a massive blackwater lagoon known as Ñakomasira. According to their cosmovision, this site is an important portal to the aquatic world and home to many spiritual beings.

Elders recount the historical encounter between the Siekopai human being and the guardian spirit of water or Añapëkë.

Siekopai youth filmmaker Melina Piaguaje documents the stories that elders share with the youth at the sacred sites of Pëkëya. She is one of several youths using film and photography to preserve Siekopai culture and amplify her people’s struggle.

The Siekopai boast knowledge of more than 1,000 plants. In this photograph, Cesar and his son Wilmer hold we’e, a fruit also known as wituk (Genipa Americana), traditionally used to dye and strengthen hair.

On the shores of a lagoon known as Onoka të’tëpa, Siekopai elder Cesar Piaguaje recounts the miraculous story of the resurrection of a shaman who visited his relatives a few days after his burial. Prior to 1941, this area was also the site of a Siekopai settlement and a yagé ceremonial house.

Pëkëya hosts 200 species of reptiles and amphibians, some 600 types of birds, and 167 mammal types. Many are threatened species, including the Amazon river dolphin, the giant otter, the manatee, and the arapaima, one of the world’s largest freshwater fish

More than 50% of the world’s land is held by Indigenous peoples and local communities, yet only 10% is legally recognized, leaving them and their forests increasingly vulnerable to incursion and deforestation. Support our work to secure land titles for Indigenous communities protecting the Amazon rainforest and our climate: