The A’i Cofán community of Sinangoe lives in a critical situation regarding its education. Without educational infrastructure and with scarce teaching materials, the teachers assigned by the Ministry of Education of Ecuador attempt to implement a curriculum that is disconnected from the A’i Cofán culture and delivered in a language foreign to its people.

According to the baseline research developed by Alianza Ceibo and Amazon Frontlines, 73% of those with a primary school education in the community have not been able to continue with upper elementary or high school studies. Far less reach university. Those who have managed to continue with their studies must leave their home communities to enroll in the nearest city.

Sinangoe is synonymous with struggle and has been in the headlines of national and international newspapers for defending the territory from mining, for demanding respect for its autonomy, and because one of its daughters – Alexandra Narváez – won the Goldman Prize for her work in the Indigenous guard. And struggle remains as the community’s path.

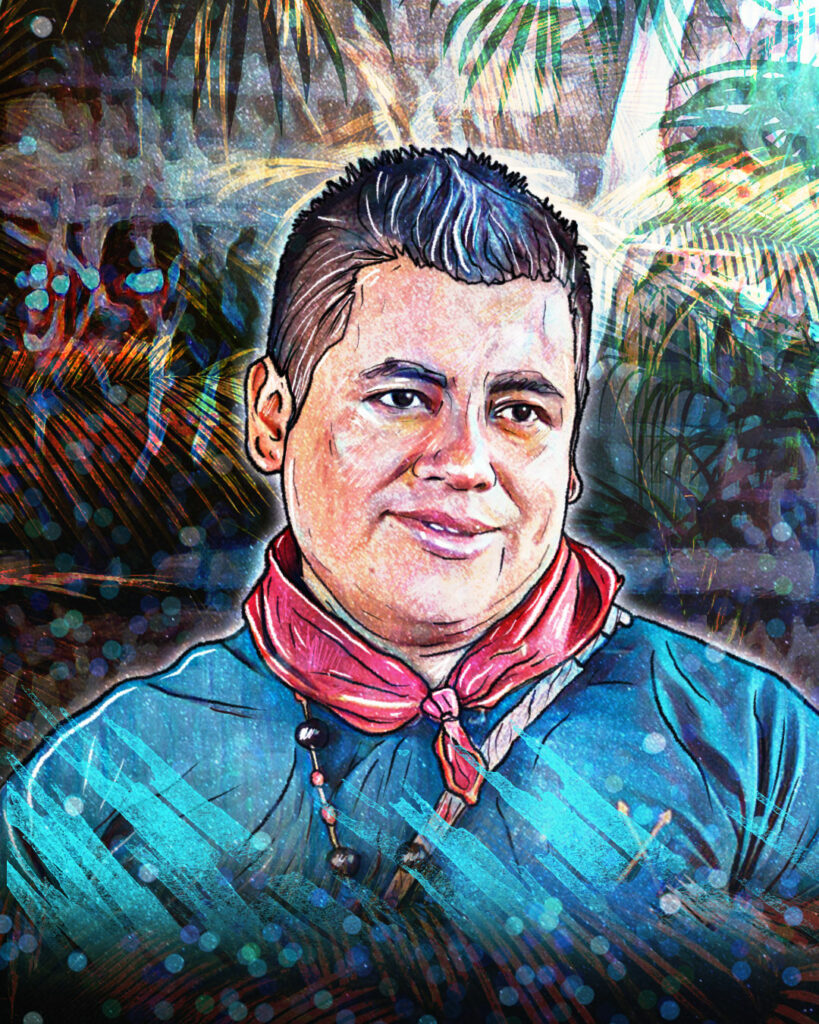

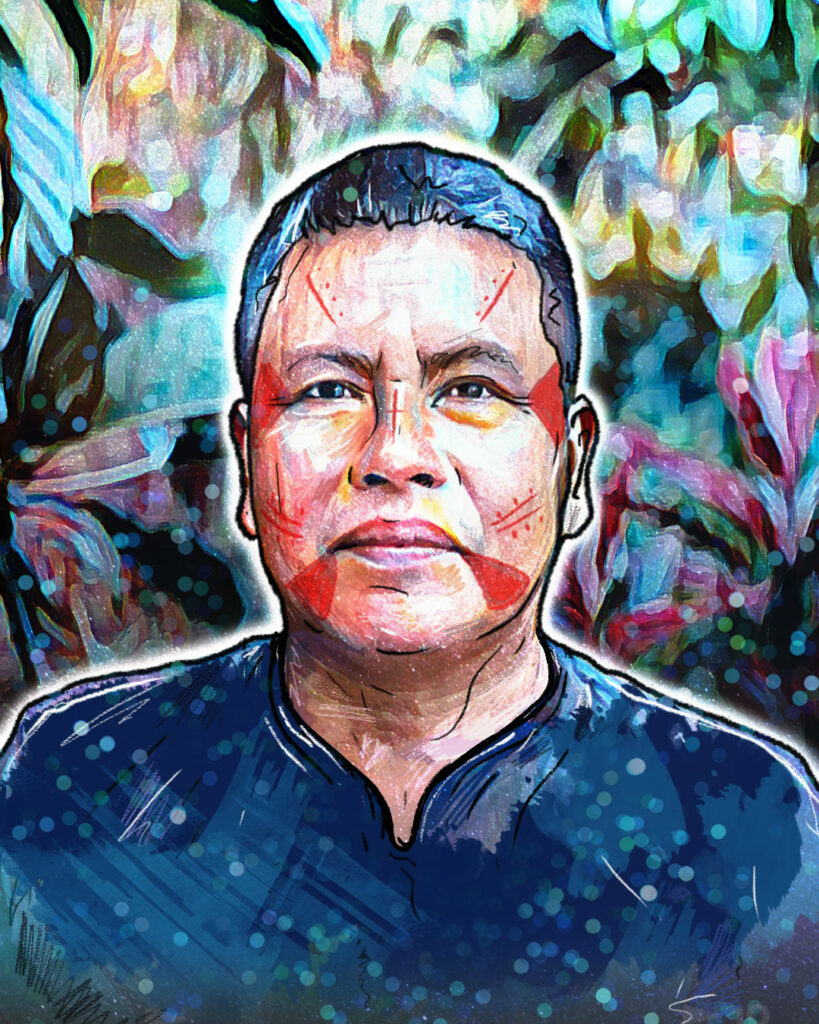

Wider Guaramag, current president of the community, tells us how they are coping with the current educational crisis, their demands for the State, and how this situation has also become an opportunity to break the traditional schemes of formal education.

Q: Wider, what was the education you received like?

A: I studied at the community school with a Kichwa teacher for all levels, because there were no Cofan teachers. To continue school and high school, we had to leave for other places within the province of Sucumbíos. All in a very traditional way.

Meanwhile at home, we had a very interesting education. I was very close to my grandmother and my grandfather. At the age of seven, I was already drinking Yocó. I prepared traditional foods and drinks of our nation. With my grandfather I went fishing, hunting. This is how we received knowledge from our grandparents.

“The first and most fundamental thing is to strengthen our own worldview and, at the same time, continue with scientific knowledge, so that when they have to leave, there is no longer the risk that learning from abroad will weaken what we have protected here in the community.”

Q: Has the education you received changed in any way from what children in the community are now receiving?

A: Although we have a Model of the Intercultural Bilingual Education System (MOSEIB) – which should guarantee the cultural relevance of education in Indigenous territories – it is scarcely applied. The teachers try, they make adjustments, but it is still an education of four walls: a blackboard, the teacher comes, instructs the class and the student memorizes. We want to break that pattern because we consider that every place can be a learning space.

At this moment in Sinangoe, we have from initial education in Year 1 up to the seventh year of basic education, that is, primary school. More or less between 2009-2013, we had the opportunity to create up to the tenth year of basic education, but it could not continue.

If education has changed anything, it is that now it is no longer a single teacher; because of so much pressure we put on the Ministry of Education we now have three teachers, although today in Sinangoe we do not even have infrastructure.

Q: Tell me, what are the biggest difficulties of having an Indigenous teacher too, but of another nationality?

A: There is a problem in communication; a teacher speaking Spanish with children who speak in our A’ingue – they do not understand each other very well and efficient teaching is difficult. It is a critical situation where due to a lack of professionals of our nationality, we have to receive teachers of another nationality such as the Kichwa, mestizos, and Siona brothers. Language is very important because without it, we can lose the transmission of knowledge.

Q: Did you feel that conventional education sought to eliminate your culture?

A: There is a minimum, perhaps in ideology, in thought. A mestizo mind is going to apply what the mestizo does. I always say that it is good to learn from the Western world, but we must strengthen and shield the worldview specific to our nationality.

Q: What is your community-led education proposal and your dream about what this should be like?

A: The first and most fundamental thing is to strengthen our own worldview and, in turn, continue with scientific knowledge; that from primary education to upper schooling, we strengthen the culture and thus, when they have to leave, there is no longer the risk that learning from abroad weakens what we have protected here in the community.

The central idea of doing our community-led education is to start from our own methodologies, how our grandmothers and grandfathers transmitted knowledge. We have analyzed that if we weave a basket, we are really applying a lot of knowledge: first nature, connection with the territory, at the same time we are applying art, fine motor skills, gross motor skills, but we are also applying logical knowledge, mathematics, geometric figures, so all this is articulated in this process.

In history, the Ministry of Education has children study the history of other countries and Ecuador, which is interesting, but for us it is important that they know how long we have been here, where we are going, what the processes of struggle have been, and then the history of the province and the country. Let our elders come and teach us how to weave the Shigra, how to make crafts, not only tell them what the Yokó is like, but go to the houses of the elders to drink it, let them say “Oh, the Yoko has been strong, it has been bitter and it gives me a lot of energy!”

Learning is not just the classrooms, but it is the entire community, it is the entire territory, it is our grandparents, it is our young people, it is our children who make any space in the territory a place of teaching and learning.

So what we want would be for all the teaching methodologies or topics that are really important for Sinangoe to be incorporated and approved in a curricular framework so that the State can guarantee their application.

We want our people to come and occupy the spaces as teachers and that we can expand education to the basic level, to high school and, why not, to university, as our brothers from the Regional Indigenous Council of Cauca – CRIC, in Colombia have. I believe that in this way, Indigenous peoples will be able to guarantee cultural and physical survival.

“It has been five years of advocating, managing, presenting documents, talking and waiting for all the state processes and the time they take, but we still do not have the new infrastructure”

And why is it so important that they approve it?

A: We are working together with the Waorani and Siekopai brothers. The idea is to move forward with this proposal, have it reviewed and approved by the community and then have an approach with the Ministry, in particular with the Secretariat of Bilingual Education. In Sinangoe, we are just now developing this curriculum, compared to the Siekopai brothers who already have it super advanced and are more ready to proceed with this approach and make this formal proposal to the Ministry of Education.

Its approval is important due to the legal issue. It is so that later our teachers do not have problems with their highest authorities in the application of the curricular framework, so that it is in order and legally registered, so that their fellow teachers can apply it within the territory.

Q: What does Sinangoe need to implement community-led education?

A: First of all, we need infrastructure. Secondly, we need the incorporation of truly well-trained teachers, not just three. We need our framework to be approved by the Ministry of Education for it to be applicable, and the most fundamental thing is that the teachers are professionalized by the territory, by our nation, so that knowledge can be transmitted within these educational environments. Also to expand the levels within the community, develop ways for our young people to not stay stuck there, but rather continue with their studies.

Something fundamental will be the linkage of the territory to our elders, that they are a fundamental axis of transmission of knowledge to the educational institution, to the children, to the teachers, but also to the entire community. It is very fundamental to be able to rescue, to be able to recover all that knowledge that our elders have and capture it in texts, in documentaries, in archives so that our future generations have that input and learn. Our elders leave us, and we in turn leave ourselves very weak for not strengthening the transmission of that knowledge to our children.

Q: Regarding the problems with the lack of infrastructure, what is the status of the construction of the school at the moment?

A: In 2018, the area where the school was located was declared unfit to receive classes due to the regressive erosion of the Cofanes River. From there we have held meetings with authorities from the Risk Management Secretariat, the Ministry of Education, the Bilingual Education Secretariat, to manage the financing, and the Ministry of the Environment to deliver the certification that is needed, because we are in a protected area. It has been five years of advocating, managing, presenting documents, talking and waiting for all the state processes and the time they take, but we still do not have the new infrastructure. We have tried to build on our own with support from Amazon Frontlines, we hope to soon have at least one classroom for the children.

Q: How is the self-education process linked to the defense of the territory?

A: We want to incorporate into the curriculum the entire history of the struggle, how our grandparents acted as guardians, and how our community carried out the entire legal struggle over the last seven years.

It is essential to transmit this knowledge of territorial protection through teaching at school, in the community. We have an Indigenous guard that has demonstrated in every way this strength, this bravery, and that it is capable of protecting from any form or action that violates our right to the territory. So the intention is to mature it, and begin to create guard nurseries where the little ones are also involved in these territorial protection processes.

Q: How do you feel being part of the development of this process?

A: There is a great responsibility to be in charge, and believe me, it is a great pride and a great honor to have received the baton of command at my age. I am the youngest to have assumed the position [30 years old when he assumed it]. The community has placed its trust in me, in the Government Council team of which we are a part. Our obligation and our challenge is to continue guiding the community, the young people, the children, through the legacy of our grandparents to be able to continue in the resistance, in the collective fight for life, for human rights, the rights of nature, and of the territory.