THE WORLD IN THE BALANCE

Across satellites, temperature stations, Indigenous leaders, and scientific researchers, an alarming message of consensus is emerging: the Amazon is facing an enormously grave crisis. Afflicted by intensifying wildfires and droughts, invaded by loggers and extractive interests, the river system that nourishes our planet could face collapse within decades.

Yet Indigenous earth defenders are fighting bravely to defend it. They know that the fate of their communities, and of the Earth as a whole, is intertwined with the protection of the Amazon. Their struggle and leadership is showing the world a clear example of how to confront the colonial logics at the heart of climate change, and live in dignity and harmony with the ecologies around us.

As we delve into their story, we have to start by landing in the Amazon itself, and thinking clearly about what we mean when we talk about rivers.

APPROACHING A RIVER

What do you see when you look at a river? What do you notice, what do you sense? What does the water remember?

“For us Indigenous peoples, rivers are highly sacred”

– explains Siona leader Alicia Salazar, amid a chatter of birdsong.

Alicia is a member of the Ceibo Alliance, an Indigenous-led organization in the Upper Amazon.

“Rivers are living beings. They are deeply alive, carrying spirits like the Yakumama that take care of fish and the life of water. Rivers are sensitive, easily hurt by intense noise and pollution. If rivers are clean and healthy, our spirits are there, taking care of us. But if the rivers aren’t healthy, the spirits leave, and so does our food. That relationship shows why we have to respect them.”

“Today, many people are losing their connection to nature, even to other human beings. They struggle to see the importance of spirituality, and see a river as just mere water. But for us these rivers are our life, our territory.”

Our home may be called Earth, but its animating force is water. Most of our planet’s surface is ocean, just as most of our own bodies are water. We may not be able to breathe underwater, yet water is what moves through us and enables our living. This intimacy is where sanctity emerges.

As A’i Cofan land defender Alexandra Narvaez, a Goldman Prize winner and central leader in a major victory against gold mining, reflects: “our spirits, as A’i Cofan people, are there in water. They protect our nourishment, our essence, our culture.”

A FOREST OF RIVERS

The lungs of our planet. The world’s largest land-based carbon sink. A dazzling and dizzying concentration of biodiversity. The conventional picture of the Amazon is of a vast forest, a dense network of abundant trees and plants.

Yet such a life-filled forest is only possible because it is nourished and sustained by a forest of waters. The Amazon is the world’s largest river system, composed of around 1,100 streams and rivers, also known as tributaries. Throughout the year, water cascades down from the glaciers and wetlands of the Andes, sweeping across and plains, pouring spectacularly into the Atlantic Ocean through the Amazon river delta. Overall, the river stretches across a staggering 4,345 miles.

Every second, the Amazon releases around 200,000 liters of freshwater into the Atlantic. At the peak moments of the rainy season, the width of the Amazon’s main waterflow can reach over 30 miles. Over the course of a year, this mighty river system moves 20% of our planet’s freshwater to the sea. If the earth is seen as a human body, the Amazon would be our major artery.

The Amazon’s unique aquatic ecology plays a critical role in regulating regional temperatures, stabilizing our global atmosphere, and ensuring our planet is livable. Our climate is a system of cycles and fragile balances. The Amazon basin is indispensable in balancing the water and carbon cycles of the world.

Such is the scale and ecological significance of the Amazon that it shapes its own weather and water cycle. Through a process known as evapotranspiration, where trees emit water vapor through their leaves, the biome produces around half of its own rainfall.

In the Amazon, trees act as powerful organisms of transformation, sucking entire streams of water through their roots, distributing it throughout their branches, and emanating droplets into the atmosphere. One single large Amazonian tree can transpire a ton (264 gallons) of water per day.

The water vapor dispersed by billions of trees across the Amazon forms what are known as ‘flying rivers’. These water streams in the sky irrigate the Amazon, snow over the Andes, and nourish the entire river system through rain. And as rainwaters from the Upper Amazon return to the lower Amazon, the cycle of hydration and transpiration restarts. It is this spiraling system of interconnection which has sustained and created the Amazon for ten million years.

For the Indigenous communities of the Amazon, rivers are enormous living beings, home themselves to a variety of spirits and beings. All these beings rely on being able to move through the liquid forest of the Amazon. While water flows downriver from the Andes to the Atlantic, many species migrate upstream into the Andes from the lower Amazonian floodplain. From turtles to pink dolphins, the Amazon’s many species complete their lifecycles by traveling between lagoons, tributaries and inundated forests. Gilded catfish, for example, migrate over 3700 miles each year, between nursery sites in the lower Amazon and spawning sites in the Upper Amazon.

These complex movements are part of what nourishes the Amazon’s astounding biodiversity; fish migrations for example are crucial in spreading seeds. As many communities and biologists have known, the Amazon is a crossroads of ‘swimways’, where watercurrents, nutrients, and species migrate and interact.

DESTRUCTION

THE AMAZON’S CONVERGENCE OF THREATS

The life-giving waters of the Amazon are under severe threat. At the time of writing, the Amazon is emerging from one of the worst droughts in its history. In 2023, many of its tributaries fell to historic lows, leaving dozens of communities without water, food or mobility. Boats were stranded. Massive schools of fish died off. Over 150 Amazon river dolphins, a highly sacred and endangered species, were found dead in overheated waters.

Indigenous leaders and scientists have interpreted the drought as an urgent warning for our warming future. What does it mean for people to be without water in the region with the world’s largest freshwater reserves?

The Amazon’s water crisis is being directly driven by global climate change, the colonization of the atmosphere by the world’s richest countries and corporations. And those very corporations and state interests are worsening the situation, through the direct colonization of the Amazon.

Over centuries, the rivers that make up the Amazon have been severely polluted, damaged and weakened by different extractive ventures. Gold miners, rubber tappers, oil prospectors. Today in the Upper Amazon, Amazonian tributaries are threatened by convergence of expanding industries: fossil fuels, agribusiness, mining, dams, and roads.

Decades of oil operations have contaminated the waters and soils, especially across large areas of Indigenous homelands, including Waorani territory. “We’ve seen major changes in our territory”, notes Waorani leader Oswando (Opi) Nenquimo, who played a key role in his people’s legal victory against Big Oil. “Today the suffering of nature can be seen through the rivers. As Waorani people, we’ve known these rivers for over a thousand years. 50 years ago, a place like Curaray was filled with fish. Today that’s no longer the case, largely because of pollution.”

Multiple dam projects, installed under the deceptive banner of ‘clean energy’, have severed the connectivity of Amazonian tributaries, especially in A’i Cofan territories. Disrupting river cycles cuts the flow of nutrients, sediments and species. Dams have been particularly damaging on fish populations, a prime source of nutrition for many Amazonian nations.

Dozens of legal and illegal mining projects have also encroached into Indigenous territory. To extract and process gold, miners often use highly toxic chemical processes, dumping heavy metals into river systems. These metals bioaccumulate in fish and in human bodies, leaving a brutal legacy of disease and damage. Today, the Amazon is a global epicenter of catastrophic health impacts linked to mercury pollution. “Our territories that we protect as A’i Cofan people risk being devastated by contamination”, Alexandra Narvaez laments. “We’re very worried. Many times mining companies will say things like – ‘it’s just some small collateral damage, it’s nothing’. But we know what that impact is on a spiritual level. It threatens the harmony of the planet and the survival of the A’i Cofan people .”

Alicia Salazar, drawing on the experiences of Siona communities, affirms that “the contamination of rivers may be the most worrying thing we’re facing. The water is more polluted by the day. Everything we need to feed ourselves, to wash ourselves, to hydrate, is polluted and that brings disease.”

From dams to mines to drills, the extractive encroachment into the Amazon is facilitated by a network of roads. These are made largely without consulting Indigenous nations, hacking through the forest, and enabling even more colonization of the area. Often roadbuilders extract sand from Amazonian riverbeds, destroying riverine ecologies both from the inside and outside.

“They, white people, are digging their own grave,” explains Alexandra. “There is a clash of visions. Companies only look at a territory to make profits. They see rivers as objects. We look at them from ourt hearts and from our spirituality. As Indigenous women, we have a connection with a territory. We regard rivers as living beings, full of life, full of strength.”

Those on the frontlines know that what is unfolding is a battle between opposing worldviews. Corporations see the Amazon as a oil well, as a ranch, as a plantation, as an open mine, as a factory. Indigenous peoples see the Amazon as life, as home, as territory.

A territory is held together by relationships, by harmony. The Amazon is an intricately connected biome, where rivers and forests rely on and build each other. But the deep interrelationships which make the Amazon a center of planetary biodiversity, are the same features which make the region so vulnerable to threats.

Deforestation, driven for example by plantation agriculture, destroys the trees that feed the ‘flying rivers’ which return water to the Andes, the source of the Amazon. Over the last three decades, the Amazon has lost over 12% of its surface water.

Destruction at any point of the river system, directly affects the fish populations migrating between the lower and upper ends of the region. In the last half-century, freshwater fish populations in the Amazon have reduced by 75%.

And as extractive forces work to insert even more disruptive projects into the heart of the Amazon, climate change is intensifying, disrupting rain cycles and heightening the risk of extreme weather. One recent study examining the most recent 2023 drought across the Amazon found that global heating made the drought 30 times more likely. For many Indigenous communities, climate change is fracturing their territorial knowledge; many plants no longer grow in the same way, many species no longer return.

Indigenous elders and research scientists fear the Amazon may be approaching a tipping point. Without drastic action to safeguard the rainforest against predatory deforestation, and pull down global emissions, the Amazon may be heading towards an irreversible horizon of drought and desertification.

PROTECTION:

STRENGTHENING COMMUNITIES OF RESISTANCE

Against such intensive threats, what can be done to protect Amazonian rivers?

Among many proposed approaches, only one has proven remarkably effective and consistent over the years: Indigenous leadership. The statistics speak for themselves. From 2001 to 2020, deforestation in the Amazon was 14 times lower inside Indigenous territories than the rest of the Amazon.

What explains this immense differential? Indigenous land and water defense relies on a range of strategies, but as multiple community leaders reiterate, there is a common root: deep connection with the territory.

“Our strength as Indigenous peoples”, Alexandra Narvez narrates, “is our unity and connection with the spirits of water, with the spirits of the territory. We continue fighting because we are defending our source of life. We know thateven more threats are coming, but as women who defend life and Mother Earth, we know we are united with the land, which gives us strength.”

Alicia echoes Alexandra’s insight, reminding that “protecting a forest requires an inward and outward perspective. Focusing inward, as Indigenous peoples we are strengthening our own spirituality, which is how we connect with and communicate with spiritual beings. With a strong connection, we can understand what those spirits are going through and need.”

Oswando Nenquimo insists on the teachings of the Pikenani, the Waorani elders, who transmit a memory of millenia. “Our Pikenani teach us the stories of the rainforest, insisting and ingraining in us to take care of the rivers and forest. Their conception of the world encourages us to struggle, to defend culture and spirit.”

Oswando reminds us that the colonial invasion of the Amazon is also educational. “Colonial schools imposed themselves, trying to change sacred knowledge. Extractive advances come with educational advances, trying to impose a mentality of commodity, of money, of the city. That’s why Waorani communities are developing their own education systems – keeping what works from external education, but ensuring youth learn the roots of Waorani spirit, and have a consciousness of the history of water, of life, of nature. That way we can resist an imposed worldview, and regenerate our own.”

We need to ensure our youth have a consciousness of the history of water, of life, of nature. That way we can resist an imposed worldview, and regenerate our own.”

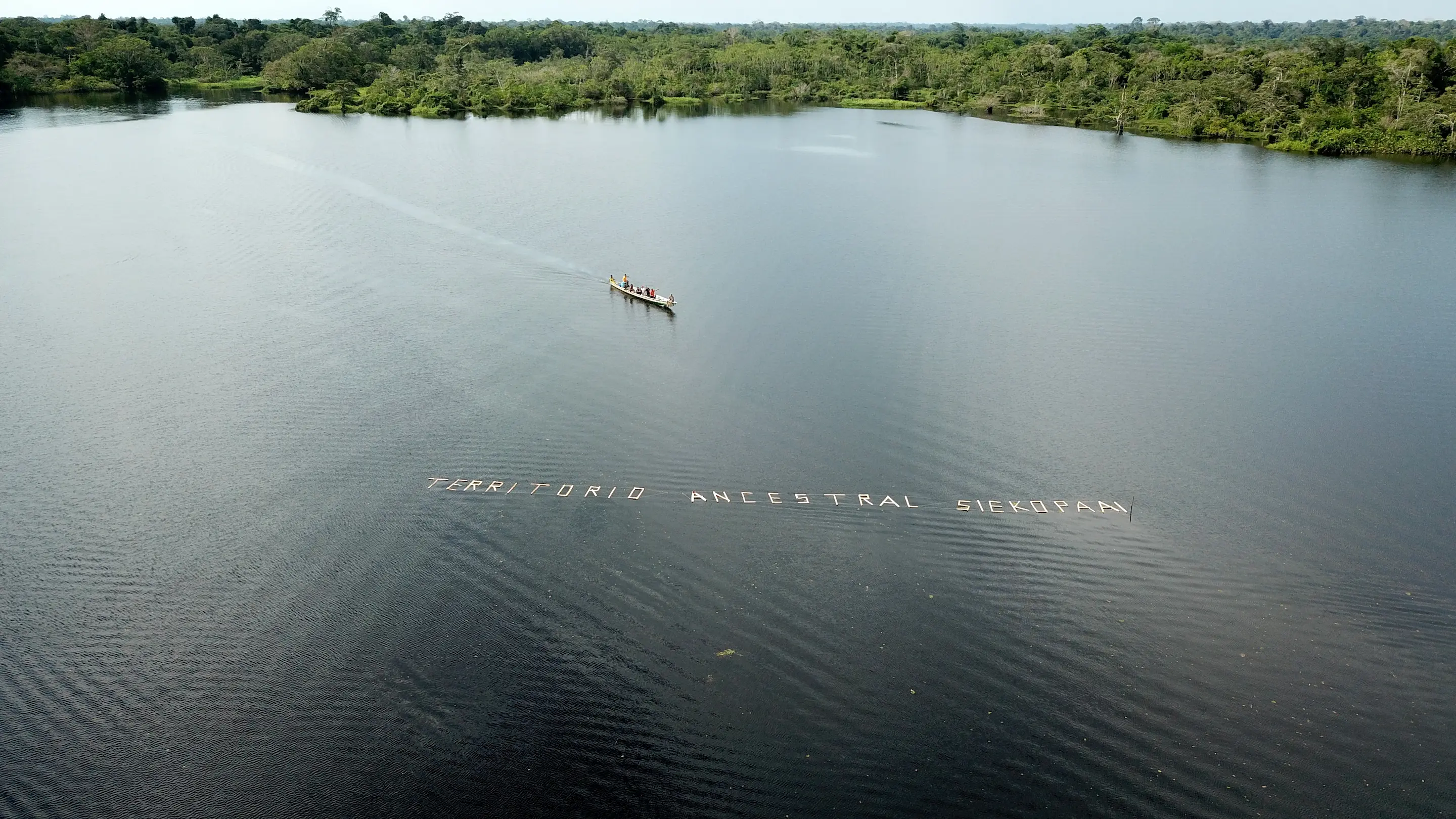

Across the Siekopai, A’i Cofan, Siona and Waorani nations, communities are strengthening their own self-governance, drawing on their culture. They are rebuilding their own educational systems, mapping their territories on their own terms, and patrolling their territory through Indigenous guards. By monitoring their lands on the ground, through legal advocacy for their rights in courts, these nations are fighting to protect their territory in the present and to guarantee future Indigenous generations a dignified life.

New collective processes are also nourishing dialogue between different elders and youth, encouraging an emergent generation of young Indigenous leaders, educators and artists.

Young Siekopai leader Milena Piaguaje for example, from the community of Secoya Remolino, is promoting ecological restoration and reforestation in her territory. As Milena reflects, ‘as a community we’re replanting because we realized we were losing many native plants. Now we’re planting medicinal plants, edible plants, and fruit trees, to have clean air and a healthy forest. The earth is sick because we as human beings are destroying so much of it – we need to care for our territories to stop extractive advances, contamination, and climate change.

Amazon Frontlines works to directly support Indigenous nations in their processes of fortifying their own power. Together, we undertake strategies that braid together territorial defense and cultural survival from multiple angles. Our collaborative efforts have led to enormous victories in Ecuadorian courts, securing land back for the Siekopai nation, protecting a half-million acres of land from extractive companies, and most recently winning the Yasuni referendum, a historic nation-wide vote where Ecuadorian citizens chose to halt oil drilling.

Yet while Indigenous communities are fighting to protect their territories from the bottom up, they are also calling for major political changes around the world and a transformation of planetary consciousness. Alicia Salazar explains that protecting the rivers of the Amazon relies on this “dual approach, strengthening communities internally, and building external support.”

Oswando Nenquimo emphasizes that the wider world needs to reckon with the violence of the ecological crisis. As Nenquimo powerfully describes, “The Amazon is a trench without a name. We must stop the war, the world must live in peace, because our planet needs peace and harmony. People all over the world need to join the struggle against the system of powerful governments and corporations, to address climate change and to improve life for all humanity.”

Such a transformation of consciousness, especially in the Western hyper-colonial world, means transforming how we understand nature itself. “Nature is something which is alive, and has its own rights”, adds Alicia.

Transforming our consciousness at its core means valuing and offering attention to our health. As Alexandra Narvez urges, “to allow pollution is to pollute ourselves, admitting we don’t want to live. It’s saying we put money first, before life. Mother Earth might not speak, but she can make us feel. Through floods, through droughts, through pollution, through illnesses. We need to respect our spirits, our rivers, for the sake of all peoples.”

It is no exaggeration to say the Amazon – the world’s largest source of freshwater – faces the risk of collapse. Unless we move away swiftly from fossil fuels, and protect by the rainforest by keeping it under Indigenous stewardship, the Amazon as we know it will not remain.

As Alicia Salazar reflects, “We simply ask for people globally to be deeply aware, to exercise their consciousness. Our rivers, our forests – all these places are alive. That’s why it’s our responsibility to take care of them. Because it’s our life in the end. Our water, our air, our food. And if we don’t care for them ourselves, who will?”